The campaigns of President Donald Trump and Democrat Mike Bloomberg have purchased airtime during the preeminent TV ad event of the year: the Super Bowl. Both scheduled spots make claims that require context or further explanation.

- Trump’s ad says “change is what we got” under Trump and then focuses on low unemployment numbers. It’s true that unemployment rates fell to “record” lows for some groups, as the ad says, but it’s misleading to suggest that’s a “change.” Rates have been trending down since late 2010 and early 2011.

- Bloomberg’s ad about gun safety claims that “2,900 children die from gun violence every year” in the U.S. But that includes many 18- and 19-year-olds who were legally considered to be adults. Annual gun deaths of those ages 0 to 17 average about half that figure.

Unemployment Trend

Trump’s campaign released one of two ads it has planned for Sunday.

The released campaign ad begins with an announcer saying, “America demanded change. … And change is what we got.” It goes on to talk about the economy. But it’s worth noting the economy was doing well before Trump took office, and the continued decline in the unemployment rate is a continuation of a trend — not a “change.”

The ad says, “unemployment rate sinking to a 49-year low.” The December rate — 3.5% — is the lowest it has been since it hit that mark in December 1969, 50 years ago. The unemployment rate was lower — 3.4% — over several months in 1968 and 1969 and was at its record low of 2.5% in May and June 1953, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

During then-President Barack Obama’s last four years in office, the rate had dropped from 8% in January 2013 to 4.7% in January 2017, the month Trump took office, and it has declined another 1.2 percentage points since. At the time, Janet Yellen, then-chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, and Ben Bernake, a former Fed chair, said the economy already was close to “full employment.” Since then, the unemployment rate has declined another 1.2 percentage points.

The Super Bowl ad highlights the unemployment rate for African Americans, saying it “fell to a new low” and the rate of Hispanic Americans, saying it “hit an all-time record low.” For African Americans, unemployment hit its lowest rate, 5.4%, in August 2019 and has edged up slightly to 5.9% as of December. For Hispanic Americans, the lowest rate was 3.9% in September 2019, rising a bit to 4.2% in December.

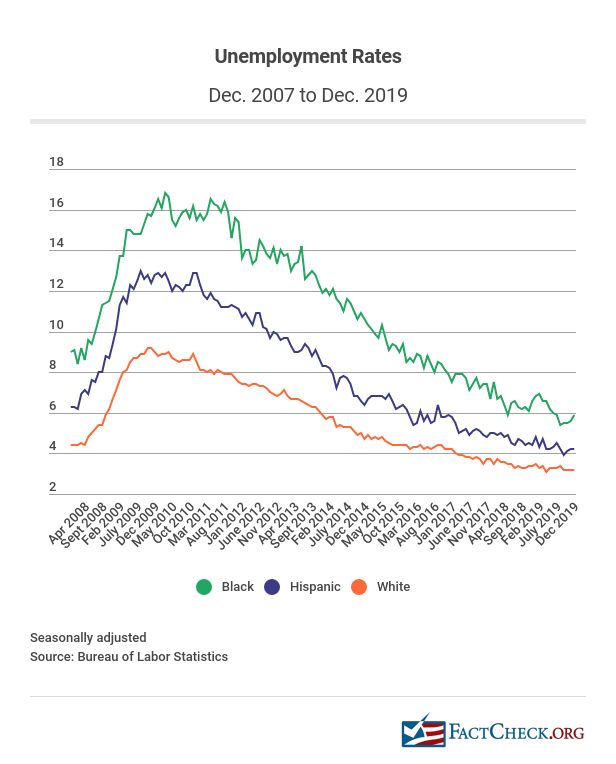

But, again, as we’ve said before, these rates reflect the continuation of a yearslong slide, beginning in late 2010 or early 2011, as the chart below shows.

When we wrote about these figures a year ago, experts had noted that the gap between white unemployment and the rates for black and Hispanic Americans had remained about the same under Trump’s presidency. The gap has narrowed a bit since — even though those racial groups continue to have higher unemployment rates than whites. According to the latest figures from BLS, the percentage point gap in January 2017 was 3.3 points for African Americans and 1.6 points for Hispanic Americans; as of December, those gaps were 2.7 points and 1 point, respectively.

The ad also says on-screen “best wage growth in a decade,” and it’s true that year-to-year nominal average hourly earnings for all workers and production and nonsupervisory workers topped 3% in August 2018 and has remained at nearly 3% or above since, according to BLS. That was the highest 12-month growth rate since it topped 3% in late 2008 and early 2009.

Experts told us these nominal figures were useful in comparing short time periods. But inflation-adjusted average hourly earnings tell a different story: Early in 2019, they hit the highest year-over-year increase since November 2015.

Over the long-term, as we’ve written, inflation-adjusted wages peaked in the early 1970s, generally declined over the next few decades and started rising again in the mid-1990s. (See our June story “Are Wages Rising or Flat?” for more information.)

Gun Deaths

Bloomberg’s 60-second commercial, which his campaign unveiled Thursday, features an emotional Calandrian Simpson Kemp of Houston, Texas, talking about her late son, George Kemp Jr., who was fatally shot during an altercation in 2013.

As Kemp calls it a “national crisis” that “lives are being lost every day” to guns, a graphic on screen says, “2,900 children die from gun violence every year.” She later asserts that the gun lobby should fear Bloomberg because “Mike’s fighting for every child.”

Bloomberg’s campaign told us the statistic comes from the former New York mayor’s own nonprofit that advocates stricter gun laws, Everytown for Gun Safety. But that organization used different language in a June 2019 fact sheet.

“Annually, nearly 2,900 children and teens (ages 0 to 19) are shot and killed, and nearly 15,600 are shot and injured,” the document said. (The emphasis is ours.)

That doesn’t include Kemp’s son, who was 20 at the time of his death nearly seven years ago. But it does include many 18- and 19-year-olds who also were legally considered adults in most U.S. states — not “children,” as the ad claims.

When limited to young people ages 0 to 17, the number of firearm-related deaths drops by nearly half to roughly 1,499 per year, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. (That’s the average over the five years from 2013-2017, the same time period used in Everytown for Gun Safety’s calculation.)

And not all of them were murdered like George Kemp or the young students at a school in Newtown, Connecticut, which could be the impression some get from the two examples used in the ad.

The majority of those — 792 — were homicides (which includes legal interventions) while 590, or around 39%, were deaths by suicide. The remainder were either unintentional deaths (88) or deaths in which the intent couldn’t be determined (30).

It is certainly not our intent to minimize the deaths of those young people older than 17, but the fact is, a lot of them, if not all, were not “children” by law.