Last month, the Biden administration announced a plan to begin administering third shots of the two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines to healthy people in mid-September to shore up potentially flagging immunity to the coronavirus.

But many scientists say that given the available evidence, which shows the two-dose vaccines still provide formidable protection against severe disease, it’s not yet clear that boosters are needed.

“What we expected from this vaccine is that we wanted it to protect against severe disease and the kind of disease that caused you to go to the hospital or ICU. That was the goal — keep people out of the hospital and keep them out of the morgue,” Dr. Paul A. Offit, a vaccine expert at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told us. “There’s no evidence that there’s any fading of immunity in that regard.”

In fact, on Sept. 3, Acting FDA Commissioner Dr. Janet Woodcock and CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky, a few weeks after backing the plan, told the White House that the FDA and CDC might only be able to make a determination on the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for a subset of non-immunocompromised people in the next several weeks. That’s because of a lack of data on both vaccines in the larger population.

Moreover, some experts say booster shots are unlikely to alter the trajectory of the pandemic much — and that the doses would be much better spent getting people around the world immunized with first and second shots.

“I’m truly disappointed. This decision is not justifiable at all looking at this data,” tweeted Dr. Muge Cevik, a physician and infectious disease expert at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, who also serves as a COVID-19 advisor to the Scottish and U.K. governments. “We are going to use up millions of doses to reduce the small risk of mild infections in fully protected [people with] a tiny risk of hospitalisation, while most of the world waits for a first dose.”

“I’m truly disappointed. This decision is not justifiable at all looking at this data,” tweeted Dr. Muge Cevik, a physician and infectious disease expert at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, who also serves as a COVID-19 advisor to the Scottish and U.K. governments. “We are going to use up millions of doses to reduce the small risk of mild infections in fully protected [people with] a tiny risk of hospitalisation, while most of the world waits for a first dose.”

The controversial announcement, made in an Aug. 18 press briefing by multiple top public health officials, proposed offering a third “booster” shot to Americans eight months after their second dose of a Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccine. According to the plan, this would mean those initially prioritized for the first two doses — primarily older people and health care workers — would also get first dibs on a booster.

The nation’s health agencies had already signed off on providing a third dose of the mRNA vaccines to immunocompromised people. The Food and Drug Administration authorized additional doses in that population for emergency use on Aug. 12, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the agency endorsed that view the following day.

Those doses, which are meant to try to bump up a lackluster immune response to normal levels, are not controversial — and they aren’t typically referred to as boosters, which is a term sometimes reserved for an extra dose that is used to restore immunity after the primary series is complete. Some scientists have argued that in healthy people, third doses for COVID-19 should also not be called boosters if a three-dose course is the standard regimen.

The mRNA COVID-19 vaccines could very well turn out to be three-dose shots, as multiple other immunizations involve three doses. But because that is not yet fully established — and the vaccine companies and federal agencies are also using the term — we will refer to third doses for healthy people as boosters for now.

While health officials repeatedly said that the decision to boost in healthy people would only occur pending review by FDA and ACIP, a specific date — Sept. 20 — was nevertheless set for the rollout to begin.

A statement, signed by all the leading public health officials, including Acting FDA Commissioner Dr. Janet Woodcock and CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky, was released the same day explaining the plan, which did not yet include a second dose for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

“The available data make very clear that protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection begins to decrease over time following the initial doses of vaccination, and in association with the dominance of the Delta variant, we are starting to see evidence of reduced protection against mild and moderate disease,” the statement reads, referring to the coronavirus. “Based on our latest assessment, the current protection against severe disease, hospitalization, and death could diminish in the months ahead, especially among those who are at higher risk or were vaccinated during the earlier phases of the vaccination rollout. For that reason, we conclude that a booster shot will be needed to maximize vaccine-induced protection and prolong its durability.”

Offit is critical of how the announcement circumvented the standard procedures. “It was just declared to be something that we were going to be doing,” he said. “It didn’t go through the FDA advisory committees, it didn’t go through the CDC advisory committees.”

And, he said, it was badly communicated. “It’s confusing to people. People think they’re no longer protected and they are protected,” he said. “I consider myself to be protected against severe disease, based on all the data.”

Other experts said the messaging could be problematic, especially for people already harboring mistrust of the vaccines. “For those who think [the vaccine is] either ineffective, experimental, or doesn’t work, the idea that there would already need to be a booster — that they’re kind of changing information around the vaccine — could certainly lead to an increased reticence to not get it,” Rachael Piltch-Loeb, a public health emergency researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told us.

Two high-level FDA employees overseeing vaccine regulation decided to leave the agency later this fall, reportedly in part because of disagreement over the booster shot decision and the way it was handled.

Before the Sept. 3 news that the FDA and CDC may only recommend boosters in more limited circumstances, it had already been unclear how the administration would be able to stick to its Sept. 20 deadline. A Pfizer representative said in an Aug. 30 regulatory meeting that the company would have efficacy data on its booster shot by late September or early October. Pfizer began submitting data to the FDA on Aug. 16 and started its supplemental approval application on Aug. 25; Moderna began submitting data on its half-dose booster to the agency on Sept. 1. The FDA’s independent advisory committee is slated to review Pfizer’s booster application on Sept. 17.

Update, Sept. 24: The CDC issued booster shot recommendations on Sept. 24, saying that people age 65 and older, residents in long-term care facilities, and people age 50 to 64 with underlying medical conditions should get a booster shot of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine at least six months after they completed the primary two-shot series. The agency said that two other groups – those age 18 to 49 with underlying medical conditions or 18 to 64 with increased risk of exposure to COVID-19 because of their jobs or institutional setting – “may” get a booster shot in the same time frame “based on their individual benefits and risks.”

On Sept. 22, the FDA had amended the emergency use authorization for the Pfizer vaccine to allow for booster shots for those groups.

In addition to real-world efficacy data, the FDA reviewed data from Pfizer/BioNTech on a subset of those participating in the original clinical trial. Pfizer/BioNTech also found that the incidence of COVID-19 among those who were fully vaccinated early in the clinical trial was higher in July and August, compared with trial participants who got their doses later. “The FDA determined that the rate of breakthrough COVID-19 reported during this time period translates to a modest decrease in the efficacy of the vaccine among those vaccinated earlier,” FDA said.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee had supported the amended EUA for those groups. It voted against recommending a booster shot of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for everyone 16 and older in its Sept. 17 meeting. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted on Sept. 23 to recommend boosters for the first three groups in the CDC’s recommendations, but not for 18- to 64-year-olds at increased risk because of their jobs or institutional setting. The vote was 9-6 against that recommendation. In a statement, Walensky, the CDC director, said: “At CDC, we are tasked with analyzing complex, often imperfect data to make concrete recommendations that optimize health. In a pandemic, even with uncertainty, we must take actions that we anticipate will do the greatest good.”

Several other countries either have plans to roll out booster shots to their populations or have begun them — most notably Israel, which is experiencing a surge of the delta variant and first promoted boosters for people 60 years of age and older, given at least five months after the second shot, before moving to individuals 12 and older on Aug. 29. But much of the rest of the globe has yet to get a first inoculation.

“We’re planning to hand out extra life-jackets to people who already have life jackets while we’re leaving other people to drown without a single life jacket,” said Dr. Mike Ryan, the executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a press briefing on Aug. 18. “That’s the reality.”

The agency has called for a moratorium on boosters for people who are not immunocompromised, at least until the end of the month, to allow the most vulnerable people in all countries to be vaccinated.

Here, we’ll explain what the studies say so far and why some scientists are skeptical of the immediate need for boosters, given the strong performance of the vaccines thus far.

The Case for Boosters

In presenting their rationale for the decision on Aug. 18, health officials pointed to multiple recent studies conducted in the U.S. that have suggested a decline in the real-world effectiveness of the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccines in preventing any kind of lab-confirmed infection.

One study, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, identified a modest decline in vaccine effectiveness against any kind of lab-confirmed infection, whether symptomatic or not — from 92% in early May to 75% in late July — in adults living in New York state, the vast majority of whom had been immunized with mRNA vaccines.

An unpublished study of patients in the Mayo Clinic Health System compared the two mRNA vaccines and found the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine began with an effectiveness of 76% against any kind of PCR-confirmed infection in January that fell to 42% in July. The drop for Moderna was smaller, from 86% to 76%.

An MMWR study of a more vulnerable population — U.S. nursing home residents — found that the effectiveness of the mRNA vaccines against lab-confirmed infections fell from 75% in the pre-delta era to 53% with delta.

Walensky also presented data that was published in the MMWR the following week, which showed a decrease in vaccine effectiveness against PCR-confirmed infection in frontline workers, from 91% before the delta variant to 66% when delta predominated. Those workers were screened weekly for COVID-19 and also were tested if they had COVID-19-like symptoms.

These declines, officials said, could be due to waning immunity over time, the delta variant or some combination of the two.

Notably, however, officials said there was not much evidence that the vaccines were working less well in protecting against severe disease. The New York study, for example, found that vaccine protection against hospitalization remained at 90% or higher for each week analyzed. And another MMWR report, which drew on hospital information from 18 states, found the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines stayed 84% to 86% effective in preventing hospitalization for 24 weeks.

Instead, the argument was that the reduced effectiveness against infection and milder forms of illness could be a harbinger of what might come — and that the government therefore wanted to plan for boosters to “stay ahead” of the virus.

“Even though this new data affirms that vaccine protection remains high against the worst outcomes of COVID, we are concerned that this pattern of decline we are seeing will continue in the months ahead, which could lead to reduced protection against severe disease, hospitalization, and death,” explained Dr. Vivek Murthy, the U.S. surgeon general.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, Biden’s chief medical adviser and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, also outlined the immunological basis for boosters, noting that antibody levels decline following vaccination; that higher antibody levels are associated with higher vaccine efficacy, which could be needed against delta; and that there’s evidence from both vaccine companies that booster shots can greatly increase antibody levels.

Officials mentioned data coming out of Israel to bolster their case, but did not cover it in any detail until a press briefing on Sept. 2. Israel has fully vaccinated almost 63% of its population, as of Sept. 1, and has used the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for nearly all of its citizens.

In the Sept. 2 briefing, Fauci noted the rising number of COVID-19 cases among the vaccinated in Israel and reviewed two unpublished papers, posted to preprint servers, documenting the effects of a booster dose in the country.

One preprint, using Ministry of Health information on people over the age of 60 who either did or did not receive a third dose, found a more than 10-fold decrease in the risk of confirmed infection and severe disease in booster recipients compared with non-booster recipients, 12 or more days after boosting.

A second preprint analyzed data from more than 150,000 people in an Israeli health care system who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the first three weeks of August. It found that seven to 13 days after a booster shot, people were 46% to 68% less likely to test positive for the virus compared with those who had not received a booster; the risk reduction increased to 70% to 84% 14 to 20 days post-booster.

“There’s no doubt from the dramatic data from the Israeli study,” Fauci said, “that the boosts that are being now done there and contemplated here support, very strongly, the rationale for such an approach.”

Recently, officials have also cited internal data along with that of other countries to support their decision, such as when Walensky was asked in an Aug. 31 press conference whether she was still confident that boosters would be available by Sept. 20, given some reluctance on the issue from the CDC’s advisory committee the previous day.

“ACIP did not review international data that actually has led us to be even more concerned about increased risk of vaccine effectiveness waning against hospitalization, severe disease and death,” she said. “They will be reviewing that as well, but it is our own data as well as international data that has led us to be concerned that the waning we’re seeing for infection will soon lead to a waning that we would see for hospitalizations, severe disease and death, which is why it’s so critical now, to plan ahead, to remain ahead of the virus.”

It is unclear what internal data Walensky might have. We reached out to the agency for more details, including when that data would be made public, but did not receive a reply.

Lack of an Obvious Need to Boost Immunity

While Fauci may be convinced by the data, other scientists are not so sure. Not only is it not yet known how helpful a booster will be long-term, they say, but it’s far from clear that they are needed in the first place.

While it depends on the goal of vaccination and is ultimately a judgment call, multiple experts told us that boosters wouldn’t be warranted until the vaccines started to be less effective in preventing severe illness, which for healthy people, hasn’t happened yet.

“The best available data that we have are that these vaccines are still working really well against the current variants and this current wave,” Johns Hopkins epidemiologist David Dowdy told us.

Some people have pointed to Israeli data that might suggest a decline in vaccine effectiveness against severe COVID-19 in older people, but no published or preprint work convincingly demonstrates this yet, Dr. Aaron Richterman, an infectious disease fellow at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, told us.

Some studies, he said — in particular a well-done unpublished study from Oxford University that involved random testing of households for SARS-CoV-2 — have observed modest decreases in vaccine protection against infection (see figure 2). But in his view, infection alone would not warrant a booster rollout.

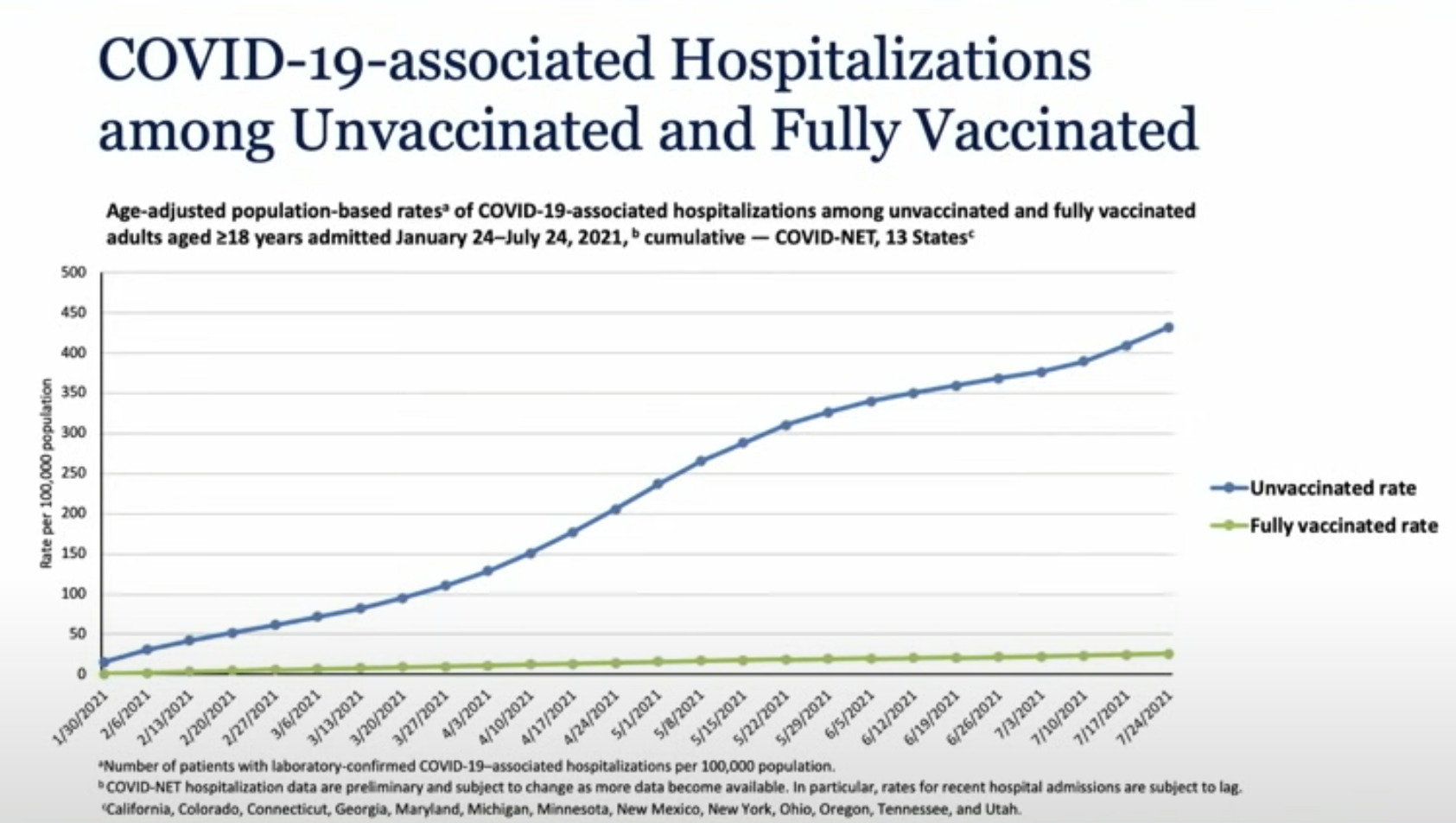

A visually compelling example of the vaccines’ preserved effectiveness against hospitalization comes from the CDC’s COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network, or COVID-NET, which tracks COVID-19 hospitalizations in 14 states.

In a plot showing the cumulative population-based rate of hospitalizations among vaccinated and unvaccinated people between January and July, the vaccinated line hardly budges, while the unvaccinated line soars upward. According to an unpublished paper presenting that data, the cumulative hospitalization rates in unvaccinated people were 17 times higher than in vaccinated people.

“From what I have seen, there is currently weak evidence at best to support the use of boosters in all people,” Richterman said.

Immunological Evidence

The immunology data also back the notion that in healthy people, the vaccines are holding steady against severe COVID-19, if not always against infection or more mild illness.

“We see antibodies going down, but we know that these vaccines make very good T cell responses and B cell responses that very likely protect from serious disease,” E. John Wherry, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania who has been studying the immune responses of vaccinated people, told us.

High levels of so-called neutralizing antibodies are needed to prevent infection entirely, or what’s known as sterilizing immunity. But if those decline, which is normal, there are still immune cells around to ward off illness — namely, the B cells that make antibodies and the T cells that assist in that process and can also kill infected cells to limit the spread of a virus in a body.

Both cell types need time to kick into gear when a person is first infected or first vaccinated, but with a second exposure, the cells can re-engage, proliferate and more quickly mount an immune response than before — preventing a person from falling very ill.

“Severe disease occurs when the virus begins to replicate unchecked in the lungs and the immune system misfires in efforts to control it,” Deepta Bhattacharya, an immunologist at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, told us. “Fortunately, the lungs are much more accessible to antibodies than is the upper respiratory tract, which is where the virus first enters. Moreover, because the virus hits the upper respiratory tract first, it buys memory B and T cells time to get going too before the lung becomes accessible to the virus. So for these reasons, protection against severe disease is expected to be maintained for far longer than protection against all infections.”

Wherry’s lab and others have shown that these long-lived and memory B and T cell responses to mRNA vaccination are durable, lasting at least six months, and likely longer.

Some unpublished work from the Wherry lab suggests that the pool of memory B cells that can recognize the virus continues to increase over time after vaccination, unlike antibodies that wane.

All of this is why immunologists suspect boosters might not be needed for a while yet.

“We could have protection against severe disease for a year, two years, three years,” said CHOP’s Offit, who nevertheless said boosters were likely eventually. “We’ll see.”

It’s also why Offit doesn’t buy the administration’s argument that fading vaccine immunity against infection or mild disease necessarily presages dwindling effectiveness against severe disease. “I think it’s built on a false premise,” he said.

Bhattacharya similarly said that he thought it would be “years” before a booster is needed to increase protection against severe disease. But if the goal is to prevent infection, then it might take annual boosters to keep antibody levels high.

A Benefit to Boosting Now?

The experts we spoke with agreed that giving third doses of the mRNA vaccines now could very well be somewhat helpful, but likely only to a limited degree — and would not be as advantageous as immunizing unvaccinated people.

“Boosting would almost certainly raise the concentration of antibodies for a while. How much clinical benefit we would see is much harder to predict,” Bhattacharya told us in an email. “Given that most estimates place the current 2-dose regimen at ~80+% effectiveness against symptomatic infections, there is not a ton of room to improve.”

“The real question is whether booster shots enhance memory,” said Dowdy. “If so, they could boost immunity for a longer period of time. But we have no evidence one way or the other on that. And also no compelling evidence that immunity from the initial vaccine series has waned to the extent that a booster is needed.”

While on the surface the Israeli studies suggest boosters might have a large impact, those effects have so far been observed only for a short period of time, and it remains unknown how long they might last.

“It would be very surprising if a third dose of a vaccine that we already know is effective didn’t decrease risk of infection by some amount over the short-term,” Richterman said. But, he added, the extra dose “probably doesn’t decrease it to the degree that these observational studies from Israel suggest because of large differences in exposure risk / behaviors between those getting the booster and those who did not.”

Richterman was especially dubious of the booster preprint that claimed a 10-fold reduction in the risk for severe COVID-19, which he said was “essentially uninterpretable” because it had a design flaw known as immortal time bias. Because outcomes weren’t counted for the boosted group until 12 days after getting the booster, he said, that group likely had less follow-up than the unboosted group, biasing the results in favor of boosters. “It takes on average 5 days from diagnosis to develop severe infection, oftentimes much longer,” he said, “so you can imagine that the boosted group has probably in many cases not even had the chance to have this outcome.”

It should be more clear what effect boosters have once the results are in from Pfizer/BioNTech’s phase 3 randomized controlled trial, he said.

Dowdy also cautioned against relying too heavily on the Israeli experience. Noting that the population of the country is about the same as the state of Michigan — and the U.S. would be unlikely to make national policy based on one state — he said, “we should be similarly hesitant to formulate national policy on data from a country the size of Israel.”

Another potential boon of boosters is their impact on reducing transmission of the coronavirus. But many scientists are skeptical that boosters will do much to bring the pandemic to a close.

“I doubt this would have a dramatic impact on the trajectory of the pandemic,” Bhattacharya said. “We know that vaccinated breakthrough infections can transmit, but the major drivers of the pandemic are still transmission from and to the unvaccinated.”

“The problem right now is not that we need to boost people who are already vaccinated. The problem is we need to vaccinate people who aren’t vaccinated,” said Offit. “The vaccine’s working, but it doesn’t work if we don’t give it.”

Relative to vaccinating new people, booster shots would be expected to be only incrementally helpful in reducing transmission and mitigating the pandemic, Richterman said. “Keep in mind that 1% of the low-income world has been vaccinated. If we want to end the pandemic, that is where the work must be done,” he added.

For its part, the Biden administration says it can “do both” — provide boosters to Americans while also helping other countries get first and second jabs. Officials have emphasized that the U.S. is the global leader in vaccine donations and announced on Sept. 2 that the government would be investing nearly $3 billion to scale up domestic vaccine manufacturing. Critics, however, say more should be done.

Beyond the ethics of working toward vaccine equity, Dowdy said a case could be made that even from a purely self-serving perspective, the U.S. should focus on helping to administer first and second doses, rather than rolling out booster shots to its own population, as that would limit circulation of the virus overall and help prevent the emergence of more transmissible or dangerous viral variants.

To Boost or Not to Boost?

Ultimately, the decision to boost is “one that’s going to have to be made in the face of imperfect evidence,” said Dowdy. The administration is in the difficult situation of trying to balance waiting for enough evidence against the risk of a surge in cases.

“I feel like the data right now to support any decisions are pretty weak,” he said. “But that’s also the nature of this. There’s no way that we’re going to be able to make the decision with great data without seeing a spike in cases.”

Several scientists said many questions remain about the best way to do a COVID-19 booster, including the number, spacing between doses and whether it’s advantageous to boost with a variant-specific vaccine or mix and match with different vaccines.

“I think that’s going to require more complicated studies to sort out,” Wherry said of the possibility of altering the timing of the doses or using mix-and-matched shots. “And I don’t know that we’re going to get to the bottom of that in the current pandemic situation.”

As for what happens next with the administration’s booster plan, we’ll learn more in the coming weeks as the FDA and CDC make recommendations and potentially release more research.

Update, Sept. 17: The CDC corrected and republished the New York study on Sept. 17, and we have updated two of the statistics from the study accordingly.

We also removed a section of this story, which explored the study’s original finding of no decline in vaccine effectiveness for people age 65 and older, but a decline in younger people and the population as a whole. The corrected study now shows a 10.5 percentage point decline in effectiveness, to 80%, for those age 65 and older. That’s still notably lower than the decline of 20.2 percentage points for the 18-to-49 age group.

We also contacted Johns Hopkins epidemiologist David Dowdy, who had been quoted in that section of our story. Dowdy told us of the corrected study: “I would still say that the trend in vaccine effectiveness over time is very gradual, with the vaccines still having 75% or greater effectiveness at the end of the time period.”

Our original story also said that another CDC study found vaccine effectiveness against infections among nursing home residents had dropped to 52% in the delta era. The correct figure is 53%.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.