A substantial body of evidence supports the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy, contrary to the suggestions of some members of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine advisory committee. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently reconstituted the committee.

Some members misrepresented the results of Pfizer’s maternal COVID-19 vaccination trial and one made misleading claims about the quality of the evidence on vaccine safety during pregnancy.

During the Sept. 19 vaccine advisory committee meeting, which focused on vaccine recommendations for this year’s updated COVID-19 shots, Retsef Levi, chair of the COVID-19 vaccine work group, said that “most” work group members thought that pregnant women should be advised to not get vaccinated against COVID-19, but that they had decided not to bring the issue to a vote before the entire panel that day.

“Most of us are extremely concerned about the safety and the lack of robust evidence, both on safety and efficacy, for not only pregnant women, but their babies,” he said. The CDC shared his comments in a video clip, highlighting the remark in a post on X.

Numerous studies have shown that the COVID-19 vaccines prevent severe disease during pregnancy, and studies have not identified an increased risk of any problems at birth, during pregnancy or for newborns.

“[W]e have really extensive evidence on the safety of mRNA COVID vaccines in pregnancy,” Victoria Male, an associate professor of reproductive immunology at Imperial College London, wrote on the social media platform Bluesky the day of the meeting. Male maintains a continually updated online explainer about COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and a table of relevant safety studies.

Levi, who is a professor of operations management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s business school, is one of 12 new members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Kennedy selected the new members after he dismissed the previous panel. Several new members have a record of spreading vaccine misinformation. Levi has previously published dubious research suggesting COVID-19 vaccines are unsafe and stated in 2023 that it was his “strong conviction” that vaccination programs using the mRNA shots from Pfizer and Moderna should “stop immediately.”

If the CDC accepts the panel’s latest decisions on the COVID-19 vaccines, there will be no specific recommendation for pregnant people. Instead, like everyone else, pregnant people will be recommended to get a COVID-19 vaccine only after discussion with a health care provider, or what’s known as shared clinical decision-making.

Update, Oct. 8: The CDC announced on Oct. 6 that it had adopted the advisory committee’s recommendations.

An HHS spokesperson confirmed that interpretation, noting that there was “an emphasis that the risk-benefit of vaccination in individuals under age 65 is most favorable for those who are at an increased risk for severe COVID-19,” and that high-risk groups included “those who are pregnant or recently pregnant.”

That would be a shift from May, when Kennedy abruptly announced that the vaccines were no longer recommended for pregnant people. (And until the CDC accepts the new ACIP recommendations, the official CDC recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy remains “no guidance/not applicable.”) At the time, HHS circulated a document to Congress that misinterpreted studies to argue against vaccination during pregnancy, as we wrote.

It would also be a change from the CDC’s previous recommendations, which encouraged vaccination among pregnant people, and different from the advice of independent medical groups, which continue to advise vaccination.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for example, recommends COVID-19 vaccination before, during and after pregnancy, including while breastfeeding. The American Academy of Family Physicians and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine similarly recommend COVID-19 vaccination during any trimester of pregnancy and during lactation.

“COVID-19 vaccine safety during pregnancy has been well established. There is no evidence of increased risk of negative maternal, pregnancy, or infant outcomes associated with vaccination,” ACOG’s guidance, updated in September, reads, citing a 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis on the topic.

The guidance explains that vaccination during pregnancy protects pregnant individuals, who have historically been at higher risk for severe COVID-19, and their babies. Infants benefit both because of the reduction in pregnancy complications and because maternal vaccination transfers antibodies to babies that can protect them against COVID-19 in their first few months of life.

Infants cannot be vaccinated against COVID-19 until they are 6 months old. Babies this age are the second most likely age group to have a COVID-19-associated hospitalization, after adults age 75 and older, according to CDC data presented at the Sept. 19 meeting.

Pfizer’s Maternal Trial Results

Much of the ACIP meeting’s discussion about vaccination during pregnancy was focused on a small trial Pfizer conducted in 2021 in healthy pregnant individuals in the U.S., Brazil, South Africa, Spain and the U.K. It included around 340 mothers and their infants, evenly divided between a vaccine and placebo group.

In explaining why the work group thought that the panel should advise people to avoid getting vaccinated during pregnancy, Levi cited the trial, stating in his presentation slides that “there was observed numerical imbalance of higher number of fetal anomalies among babies born to vaccinated women (8 vs. 2).”

Earlier in the day, ACIP chair Martin Kulldorff, a biostatistician and epidemiologist formerly with Harvard University, also pointed to the imbalance, which he said was included in materials Pfizer provided to him prior to the meeting. He called it a “fourfold excess risk of birth defects” that was “very concerning,” adding that he had calculated his own p-value for the figures, and it was 0.05 — the typical threshold for determining whether a result is statistically significant.

In a vote that passed, the panel also agreed to recommend an update to the CDC’s COVID-19 vaccine information statement to include mention of the “observed numerical imbalance.” (Dorit Reiss, a professor at University of California Law San Francisco who specializes in vaccine law and policy, told us that changing the VIS is an “elaborate process” that ACIP has no authority over, so the vote was “at most persuasive.”)

Experts told us that a closer look at the trial results, however, shows that the imbalance is not indicative of a legitimate concern. Most, if not all, of the observed birth defects occur in early pregnancy or are genetic and could not have been caused by the vaccine, which in the trial was administered only during the latter part of the second trimester or in the third trimester. None of the defects was determined by trial investigators to be vaccine-related.

“Their comment highlighting the ‘observed numerical imbalance’ is completely inappropriate and misleading, IMO, given that the events occurred before randomization,” Jeffrey S. Morris, director of the biostatistics division at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, told us in an email. “It creates the false impression that the study provided suggestions that the vaccines may increase risk of birth defects, when the study says NOTHING of the sort.”

When Kulldorff asked about the imbalance during the meeting, a Pfizer scientist, Dr. Alejandra Gurtman, disputed that there was a “fourfold rise” and pointed to other numbers for congenital abnormalities — “about 5%” in the vaccinated group versus 3% in the placebo group. She also said that the rates seen in the trial were not higher than the expected background rate, and that most of the birth defects were first trimester defects. There was then a lengthy exchange over what the correct numbers were.

More than a week after the ACIP meeting, Kulldorff raised the issue again, writing on X that the trial “found birth defects in 8 babies to 156 vaccinated pregnant mothers and in 2 babies to 159 unvaccinated mothers, for a relative risk of RR=4.1, p=0.049. When asked at ACIP meeting, Pfizer did not explain.”

The eight versus two birth defects is noted on a webpage Pfizer posted on Sept. 9. “This incidence is within the range observed in the general population, and events were not deemed to be vaccine related,” the webpage states, going on to note that other research has not identified a link between COVID-19 vaccination and birth defects.

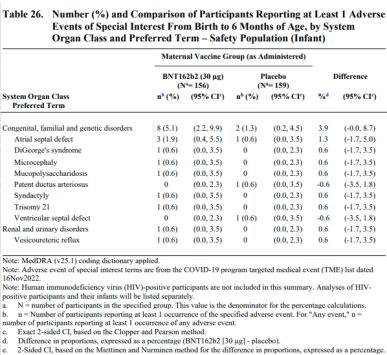

A more detailed document about the trial, added to the Pfizer website on Sept. 9, also reports the eight versus two figure, which pertains to birth defects categorized as adverse events of special interest, which includes major congenital anomalies and developmental delays. The events occurred at a rate of 5.1% in the vaccine group versus 1.3% in the placebo. Other measures show smaller discrepancies. For instance, when counting birth defects by serious adverse events, there were 9 in the vaccine group versus 5 in the placebo, or rates of 5.8% and 3.1%.

The more than 2,100-page document explains that “none of the events were assessed as related to treatment by the Principal Investigators,” and except for one birth defect observed in the placebo group, “the observed congenital anomalies usually either arise in the first or second trimester or are present at conception.”

Comparing the results against what is expected in the population, the document continues, “the data did not suggest an increased risk for congenital anomalies after vaccination in pregnancy.” It goes on to note that registries and other safety studies have not identified any safety signals for the vaccine during pregnancy.

Indeed, three of the eight defects reported among infants born to vaccinated mothers are genetic and would be present at conception, including Down syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome and mucopolysaccharidosis. Syndactyly, or webbed fingers or toes, which occurred in one instance, often runs in families and occurs by the eighth week of pregnancy. Atrial septal defects, which occurred in three babies born to vaccinated mothers and one born to a mother given placebo, also occur in the first trimester as the heart forms. (A pediatric cardiologist told us that some of the atrial septal defects and the patent ductus arteriosus recorded in the trial are considered normal in newborns and would not be classified as true congenital heart defects.)

Microcephaly, or a small head, which occurred in one child born to a vaccinated mother, can be genetic or related to an injury or to certain maternal infection or exposures. The condition is typically only identified in the late second or third trimester, but can arise earlier. In the case of Zika infection, for instance, microcephaly is much more likely when the infection occurs in early pregnancy.

Beyond the eight special interest birth defects among children born to vaccinated mothers, there was one case of polydactyly, or extra fingers or toes, which occurs very early in pregnancy, and one case of congenital rubella syndrome. The syndrome results from maternal rubella infection, almost exclusively before 20 weeks.

Kulldorff suggested that the eight versus two difference in birth defects was statistically significant, but Morris and Male disputed that, saying that Kulldorff’s calculation appeared to be incorrect. Male also said that in her view, it wasn’t appropriate to pool such different birth defects together anyway. When analyzed individually, none of the individual defect results were statistically significant.

Even if the result was statistically significant, it still wouldn’t matter, Morris said, since “it would be a spurious result coming from unfortunately imbalanced randomization and clearly not a vaccine causal effect.”

Male also pointed out that because the trial was small and did not vaccinate pregnant people until 24 to 34 weeks of pregnancy, the trial “wasn’t really able to assess whether the vaccine causes” most birth defects. That’s where large-scale observational studies are helpful, she said.

“Among six such studies that I know of, looking at a total of 54,085 people vaccinated against COVID in the first trimester of pregnancy, there was no evidence of any increased risk of congenital abnormalities associated with vaccination,” she said. “Two of these studies were by the CDC and their results (or in some cases, interim results) have been presented in past ACIP meetings and informed the vaccines recommendations that ACIP, as previously constituted, made.” (Male was referring to these studies.)

When asked why he was interpreting the trial data as a safety concern given the full context, Kulldorff emphasized that Pfizer did not provide clarity during the meeting.

“I asked them about these numbers during the meeting. Surprisingly, they neither confirmed or denied the numbers, nor have they provided an explanation afterwards,” he told us in an email. “When an [im]balance like this is found in a randomized clinical trial, that should be thoroughly investigated. It is the responsibility of Pfizer to do so. That is why I asked the question during the ACIP meeting, but Pfizer did not mention any follow-up investigations to explain the results, and I do not know what follow-up investigations they did.”

Levi did not respond to a similar request.

A Pfizer spokesperson told us that the company “shared all available data from the trial” with the ACIP members, which included Pfizer’s interpretations and explanations of the birth defect results.

The spokesperson also said that Gurtman, the Pfizer scientist, did not have the tables in front of her, and had provided figures for the selected adverse event birth defects, calling it a “miscommunication and misunderstanding on her part of which tables [Kulldorff] was referring to.”

“Investigators were to report safety data relating to birth outcomes and congenital anomalies according to recognized guidelines,” the spokesperson said in an emailed statement, which noted that there were various ways this was reported in the study. “When looking at the totality of data reported, for those categorized as major abnormalities, there was no statistical difference in the rates” of the vaccinated and placebo groups, and “the abnormalities observed were either genetic or occur during organogenesis in the first trimester, and therefore could not be related to vaccination.”

Misleading Claims About Evidence Quality

One of Levi’s central arguments for opposing vaccination during pregnancy is the lack of more robust data from randomized controlled trials.

“No appropriate randomized clinical trials to show efficacy and safety,” his presentation slide about pregnancy reads, before noting the small trial’s birth defect imbalance.

But experts told us that the focus on trial data is misplaced.

Observational studies aren’t perfect. But for safety, Male said, they “are more sensitive than clinical trials.” That’s because for rare adverse events, even a very large trial may not detect them. In contrast, observational studies, including those based on vaccine safety surveillance systems used in multiple countries, can much more easily include large numbers of people and identify real but rare side effects.

In the case of pregnancy, gathering large trial data was not possible because the original trials excluded pregnant people, as is typical for medical products, nor is it ethically possible to conduct those studies now. Some of those trial participants did get pregnant, however, and there was no indication from that limited data that there was any safety issue. Pfizer then conducted its maternal vaccination study, but it ultimately was a small study, as it stopped enrolling participants after the COVID-19 vaccines were widely available and recommended during pregnancy.

Other studies show that pregnant people mount strong antibody responses as a result of vaccination, and that vaccination is associated with protection from a variety of poor outcomes, with no observed safety issues — all consistent with the vaccines working and being safe during pregnancy, as we’ve said.

Levi, however, appears to discount these studies. Later in his presentation, one of Levi’s slides included links to three papers and stated: “Observational studies are of very low-quality with structural biases, and some raise concerns.”

Two of the papers support the vaccine’s safety during pregnancy, and a third is Levi’s own paper, which is a 2025 critique of a 2022 Israeli safety study that also supported vaccination during pregnancy.

The authors wrote a response to his critique, noting that their study was too small to control for gestational age, as Levi suggested, but that other studies published since have done so and have similarly found no association between COVID-19 vaccination and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

One of the linked studies is a Canadian study from November 2023 that found no association between COVID-19 vaccination and an increased risk of miscarriage. Earlier this year, the HHS ‘FAQ’ cited the paper to argue against vaccination, since the unadjusted rates of miscarriage were slightly higher among those who were vaccinated versus those who were not. But an expert told us at the time that such an interpretation of the study is a “clear misrepresentation,” with Male noting then that it is “inappropriate” to look only at the raw data in such a study.

The other is a 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis, which found no increased risk of miscarriage among women vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy. It is not immediately clear why Levi highlighted the paper, but several known purveyors of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation published a letter to the editor about the paper, claiming that their analysis of reports to a safety monitoring system should have been included, which would “lead to a conclusion of excess harm, necessitating a worldwide moratorium on the use of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy.”

The authors of the review responded, noting that the analysis could not have been included, as it reported its results relative to influenza vaccination, unlike all the other studies. “Should the authors provide robust factual data on the true incidence of miscarriage following the use of COVID-19 vaccines, we would be more than happy to update our meta-analysis accordingly,” they wrote.

Male said that observational studies “certainly have their challenges,” since people who get vaccinated may be different from those who don’t, and in pregnancy, it can be important to take into account how risks change over time, among other factors.

She said that some early studies “did not fully take account of all these things, because complete data was not always available at the time.” Still, she said, it was important to do the studies in case they might have revealed important safety concerns. With more time, however, larger datasets with detailed information became available. Now there are “large numbers of very robust observational studies on the safety and effectiveness of COVID vaccination,” Male said.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.