In unveiling new dietary guidelines, federal health officials have claimed they are correcting past guidance that created a “generation of kids low in protein” and that Americans should get “dramatically” more of the nutrient. While some individuals may benefit from more protein, Americans are not generally protein-deficient.

In fact, many Americans, including a majority of children, already meet or come near to meeting the lower end of the higher daily protein goals promoted in the new guidelines, which range from 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. There’s some uncertainty about how much protein people should consume for optimal health. Multiple factors affect protein needs, which may be higher for older adults, as well as for people who are building muscle through exercise or actively losing weight.

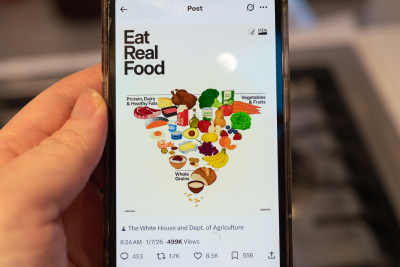

Despite this nuance, officials portrayed the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, released Jan. 7, as righting a clear wrong, while misleadingly stating or implying that Americans in general need to eat significantly more protein. The new guidelines include an inverted food pyramid that prominently features a large steak, and the website promoting the guidelines proclaims, “We are ending the war on protein.”

“The old guidelines had about half the protein that you need,” Dr. Marty Makary, the Food and Drug Administration commissioner, said during a Jan. 9 appearance on CNN. “Look at the consequence of the old, corrupt food pyramid: a generation of kids low in protein, struggling with muscle mass, weak, having trouble concentrating, addicted to ultraprocessed foods and refined carbohydrates.”

“The science was clear enough on proteins that we should dramatically increase our input of proteins,” Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said during a Jan. 21 rally.

Nutrition experts we interviewed objected to the idea that Americans in general need to “dramatically increase” protein intake, or that children are broadly deficient. HHS did not reply to an email asking for more information to support these claims.

“When you look at most intake surveys, most Americans were getting in the range of intakes that is being recommended, close to 1.2” grams per kilogram of body weight per day, Stuart Phillips, a professor who studies the effects of nutrition and exercise on skeletal muscle at McMaster University in Canada, told us.

For reference, the recommended range would translate to around 108 to 144 grams of protein per day for a 199-pound man or 94 to 125 grams per day for a 172-pound woman, the average weights for U.S. adults. A 3-ounce serving of chicken breast has 26 grams of protein; a 3-ounce serving of cooked salmon has 19 grams; half a cup of cooked lentils or white beans has 9 grams; and a cup of milk has 8 grams.

Moreover, “probably less than 5% of the U.S. population eat diets that are consistent with the previous dietary guidelines,” Wayne Campbell, a Purdue University professor who studies nutrients, foods and dietary patterns, told us. “It is an inappropriate attack on past guidelines to say that the guidelines are the reason why everybody eats a poor diet and is not as healthy as they hopefully would be.”

“There is no evidence of widespread protein deficiency in the U.S. population,” Dr. Frank B. Hu, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told us.

Previous editions of the dietary guidelines did not give a particular figure for the amount of protein people should eat, experts said. Hu explained that a different group of experts helps set daily recommendations for specific ranges of protein and other nutrients.

“Who is going to track how many grams per kilogram body weight of protein” they are eating? Wendi Gosliner, who leads research projects at the University of California’s Nutrition Policy Institute, told us, noting that the guidelines are meant to guide federal food programs and nutrition education by providing advice that is “digestible” for the general public.

Raising protein intake recommendations requires data showing “widespread protein inadequacy” or that there are benefits to eating more protein beyond the minimum, Hu said. “We don’t have any of those data at this point to substantially increase protein intake recommendations” for the general population, Hu said. He added that an argument could be made for relatively high protein intake for certain segments of the population, including people on weight loss drugs, older adults and people engaged in physical activity that builds muscles.

Some experts are supportive of the protein recommendations in the new guidelines.

Phillips, who was not involved in the guidelines, said that the new range is “more in line with what I would recommend,” agreeing the evidence is particularly strong for certain subgroups and depends on physical activity level. However, he disagreed with the implication that prior guidelines led to widespread deficiency.

Claims that the old food pyramid “produced a ‘generation of children low in protein’ or broadly impaired muscle mass or cognition are not supported by direct evidence,” Phillips told us. “Childhood health challenges are far more plausibly linked to excess energy intake, poor diet quality, physical inactivity, and high consumption of ultra-processed foods than to insufficient protein per se.”

(To be clear, the new food pyramid does not replace the original 1992 food pyramid people may remember, which was replaced by another, less hierarchical pyramid in 2005 and then MyPlate in 2011.)

“My takeaway from all of it is that we’ve elevated protein in people’s thinking, it’s front and center, and we gave people very specific goals,” Donald Layman, a protein biochemist and professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told us. “I think we’ve made an enormous step forward in clarity.” Layman, who is also a food company consultant, owns a fat loss company that sells meal replacement shakes, although he told us he has lost money on this latter endeavor.

Layman and nutritional physiologist Heather Leidy of the University of Texas at Austin co-authored reviews of the effects of the new recommended protein range on weight management and nutrient adequacy for HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the agencies that produce the guidelines.

Unusually, Layman, Leidy and seven additional scientists were asked to perform these reviews in under three months, according to STAT. A 20-person committee of nutrition researchers had previously spent years identifying research questions, reviewing the literature and formulating recommendations. The scientific advisory committee does not write the guidelines, but their conclusions inform them. The guidelines in the past have been credited to a list of HHS and USDA staff, although this year’s guidance document does not name authors.

Muddled Messages on the Role of the Dietary Guidelines

Makary has repeatedly said that the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans increased recommended daily protein intake by “50% to 100%.”

It’s true that the new recommended intake of 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day is 50% to 100% above the Recommended Dietary Allowance of 0.8 grams per kilogram per day for adults. (Children have somewhat higher RDAs, when measured per kilogram of body weight.) These RDAs were established to set baselines for nutrients to prevent deficiency in the vast majority of Americans.

But to be clear, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans do not set RDAs, Campbell explained, which are instead set via a process led by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine.

The RDA is “not a recommendation for people to purposefully try to eat that amount of protein,” Campbell said, but rather represents an amount people should not fall below. “If you’re eating 1.0 gram per kilo, 1.2 or 1.4 — or even very few people eat 1.6 — then that’s all within a range … that the 0.8 would support.”

The RDAs, along with other values, inform the dietary guidelines. However, Campbell said that the guidelines are meant to recommend which food types to eat, not particular nutrient intakes. Researchers do modeling to ensure what they are recommending “meets or moderately exceeds” the nutrient minimums, he said. He was not involved in the current guidelines but served on the scientific advisory committee for the 2015-2020 guidelines.

Campbell said that the current RDA was based on the best evidence available in the early 2000s, when it was last reviewed, and that there’s “inconsistent” evidence since on whether it should be changed. Ann Yaktine, director of the Food and Nutrition Board, told us that protein is among the nutrients set to be updated, although she said she could not predict a timeline. Until that update is complete, she said, the current RDA “will remain,” adding that RDAs and other nutrient-related values inform the dietary guidelines, “not the reverse.”

For Most, No ‘Dramatic’ Increase in Protein Needed

Americans mostly exceed the minimal requirement to prevent protein deficiency and, in many cases, even meet the higher goal set in the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

“The consensus has not been that there is a dramatic shortage of protein in this country,” Gosliner said, contrary to Kennedy’s claim that Americans need to “dramatically” increase intake.

Using survey data on American diets collected by the U.S. government, researchers have estimated that adults on average get near or even slightly above 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day — the bottom of the range now recommended by the dietary guidelines.

“Because the intake of protein is already pretty high, especially animal protein, in the U.S. population, there is no evidence that further increasing protein intake, especially in a major way, will confer significant health benefit,” Hu said.

However, Layman pointed out that there’s variation in how much protein Americans consume. The people who already consume protein within the new recommended range do not need to increase their intake, he said, but some people “need to dramatically increase” protein intake.

A 2018 study on protein intakes between 2001 and 2014 shows that nonelderly American adult males on average exceeded 1.2 grams per kilogram, but that the average fell to closer to 1.0 as they aged. Women on average got between approximately 1.0 and 1.15 grams per kilogram per day, with amounts also falling with age.

Phillips also said there was room for improvement in protein consumption. “Many Americans meet the RDA only marginally, consume protein in uneven daily patterns, or obtain it largely from low-quality, ultra-processed sources,” he said. However, he added that most Americans “are not protein deficient in the clinical sense.” He cautioned against framing the new recommendations as being driven by deficiency, rather than a way to optimize certain outcomes.

Makary’s claim that prior guidelines led to “a generation of kids low in protein” also overstates the prevalence of protein deficiency in the U.S.

“It’s not like there’s growth stunting on a large scale in the United States because kids are protein deficient,” Phillips said. “It’s disingenuous at best and flat out wrong at worst.”

The 2018 study found that virtually no children age 8 and under ate less than the RDA — the level meant to prevent deficiency in the vast majority of the population. Protein underconsumption did rise with age for minors, with 11% of teenage boys and 23% of teenage girls not meeting the RDA.

Most age groups of children, both male and female, on average exceeded 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. The exception was adolescent girls, who consumed around 1.1 grams of protein per kilogram daily.

Layman acknowledged a relative lack of research on children and protein intake but also pointed to data showing that adolescents are at risk of not eating enough protein. He also listed the many poor health outcomes for American children today and argued that past guidance had preceded changes in kids’ diets.

“We know it’s not working,” he said. “We know that after the original guidelines in 1980 that mothers, thinking they were doing the right thing and avoiding cholesterol and saturated fat, switched from having eggs and bacon and milk at breakfast to having Pop-Tarts and Cap’n Crunch and orange juice.”

However, Hu detailed a long list of factors other than protein that have led to childhood obesity and other metabolic conditions. These include generally low-quality diets in an obesity-promoting environment, lack of sufficient sleep, inactivity and excessive social media use. “Those are all important drivers of adverse health incomes in children,” he said. “I don’t think protein inadequacy or protein deficiency is a major driver.”

“I wish I could tell you that I thought that … we just haven’t been feeding kids enough protein, particularly animal protein, and that’s what’s causing all of the very sad dietary-related challenges that kids are experiencing,” Gosliner said. “From my perspective, there is no evidence of that being true.”

More Protein May Benefit Certain Groups

A separate question is whether people are generally healthier if they consume substantially more protein than the RDA’s minimum requirement.

Campbell said that this is a challenging question to answer rigorously. “It’s very difficult to do controlled feeding studies of sufficient length to actually feed people different quantities of protein for months on end to see what happens to them,” he said.

“Where the science is strongest is in showing that certain groups benefit from protein intakes above the RDA,” Phillips said. “Older adults, people engaged in regular resistance or endurance training, individuals recovering from illness or injury, and those intentionally losing weight all appear to achieve better outcomes at intakes closer to 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day. In these contexts, higher protein supports the maintenance of lean mass, functional capacity, and satiety.”

However, Hu criticized the new guidelines for setting this intake goal broadly, saying that they “are not designed for specific groups of U.S. adults,” but rather the general population.

In a Jan. 7 opinion article in the Free Press, Makary and an FDA co-author referred specifically to benefits of higher protein intakes for weight loss. “Eating more protein in line with these recommendations consistently improves weight and body composition without harm,” they wrote.

Layman and Leidy’s review, used to justify the new guidelines, concluded there was “moderate to strong” evidence that eating protein within the new recommended range promotes weight management.

However, Gosliner said that the review relied on studies of people engaged in weight loss, which are not necessarily generalizable. “They are extrapolating that to the entire population, which doesn’t make sense,” she said.

Layman countered that 75% of Americans are overweight or obese. “Should they basically be guidelines to keep people fat or to get people to ideal weight?” he said. He said that the weight loss studies included in his review in many cases included a maintenance period where people were not restricting calories.

But just because many Americans could benefit from calorie restriction or strength training does not mean that most adults are engaging in these behaviors, other experts said.

A higher protein diet while people are “purposefully energy restricting their diets to lose weight” may help people maintain lean tissue and muscle, Campbell explained. But protein is “not going to be a magical solution for you to actually permanently keep any weight off.”

“Protein without resistance exercise, during weight loss, does very little,” Phillips wrote in a Jan. 6 article on protein hype published in the Conversation. “Exercise is the major driver that helps lean mass retention. Protein is the supporting material.”

Phillips also pointed out that older adults, who can benefit from higher protein intake, make up an increasing share of the population. Protein is “important,” he said, “but it is not a stand-alone solution to metabolic health, childhood development, or healthy aging.”

Overall Diet Also Matters

The impact of the new dietary guidelines will depend on how people interpret them, some experts said.

Phillips wrote in his Conversation article that 2025 was the year protein “jumped the shark,” explaining a cultural context where it has been “oversold, overvalued and overhyped.” One concern, he told us, is that people will think they are doing “something good for their health” simply by increasing their protein intake, even if they are already consuming a relatively high amount.

If people eat “substantially” more protein, it could increase the risk of chronic disease, Hu said, explaining that consuming too much protein — and particularly animal protein — is associated with increased risk of chronic disease. “It depends on what comes together with the protein,” he said. For example, he said, people who consume more animal protein also consume more saturated fat, cholesterol and “other unhealthy components.”

“At the end of the day you are eating foods for multiple compounds and nutrients, not just protein,” Campbell said.

The guidelines themselves encourage eating a “variety” of protein foods from animal and plant sources, but the new food pyramid prominently features a large steak in the upper left-hand corner, with nuts and legumes further down.

The original committee tasked under the Biden administration with the scientific review for the dietary guidelines recommended an emphasis on consuming more peas, beans and lentils and less red and processed meat. The new dietary guidelines rejected this advice, with the exception of recommending against processed meat.

If someone replaced refined carbohydrates and sugar in their diet with plant protein, lean protein and eggs, that would be “reasonable,” Hu said. But people who consume a large quantity of animal protein tend to eat significantly less nutrient-dense plant protein sources, he said.

Further, Hu said, supermarkets are now stocked with numerous highly processed protein products.

The new guidelines discourage eating highly processed foods. But Gosliner reiterated that people often do not follow dietary advice. “There’s no reason to think now that if protein is all the rage and people are saying, ‘Eat more protein,’ that you’re not going to start seeing ice cream with protein powder and cookies with protein powder.”

When asked about the risk of the new guidance feeding into the current trend for promoting highly processed foods as sources of protein, Layman replied, “I think you need to step back and look at the guidelines. What’s the opening words? Eat real food.”

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.