Sen. James Inhofe says there has never been “an instance of ground water contamination” caused by hydraulic fracturing — fracking — for oil and natural gas. Inhofe’s office told us he is referring only to “the physical act of cracking rocks through hydraulic fracturing.” But drilling operations that involve fracking include other actions that have caused contamination.

A peer-reviewed study published in 2014 found that drinking water wells near fracking sites in Pennsylvania and Texas were contaminated with methane that had the chemical signature of gas normally found only deep underground.

Rob Jackson, a Stanford University professor of earth system science who coauthored the 2014 study, told us that drilling that uses hydraulic fracturing has “contaminated ground waters through chemical and wastewater spills, poor well integrity, and other pathways.”

The Fracking Boom

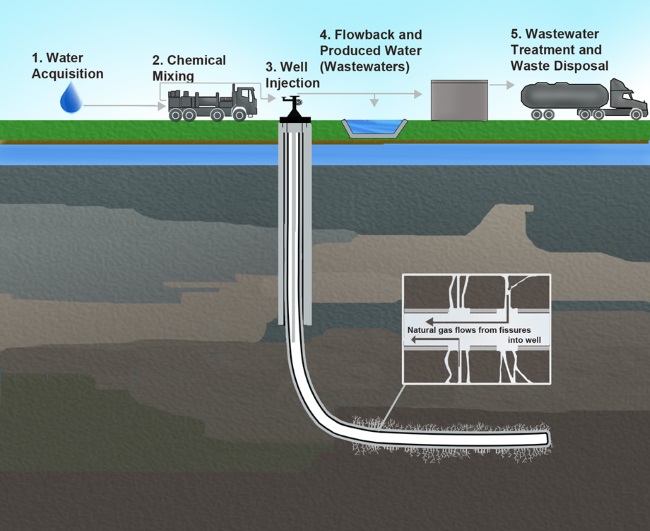

Fracking involves injection of a large volume of water, sand and a cocktail of chemicals (known as fracking fluid) deep underground to fracture the rock and allow gas to seep out. It is also used for oil extraction. (See EPA diagram at bottom.)

In common usage, the term “fracking” is sometimes used to describe the entire process of drilling for natural gas, but that isn’t accurate. After a well is drilled, cemented and prepared in other ways, only then is the well “fracked” — the actual stimulation of rock far beneath the earth’s surface to allow extraction of the gas.

Although hydraulic fracturing has been in use since the late 1940s, better technology and changing economics have led to a recent boom in natural gas extraction, in particular from shale formations. U.S. production of shale gas rose by almost 500 percent between 2007 and 2013, according to the Energy Information Administration.

With this boom, however, have come questions regarding water contamination related to drilling activity. This could occur through a number of mechanisms, including spills of gas or fracking fluid at the surface that could leach into groundwater, faulty cement casings inside wells allowing seepage of gas into the water table, and failed pieces of the well, such as steel and cement.

Partially in response to those concerns, the Department of the Interior finalized a regulation on March 20 regarding hydraulic fracturing and related activities on public and tribal land. The regulation includes a number of provisions related to fracking and other aspects of natural gas drilling activity.

For example, the rule includes “[p]rovisions for ensuring the protection of groundwater supplies by requiring a validation of well integrity and strong cement barriers between the wellbore and water zones through which the wellbore passes.” It has specific requirements for constructing cement casings for wells, and monitoring pressure on certain well parts during fracking operations. And it also requires disclosure of the chemical contents of fracking fluids.

Inhofe, a Republican from Oklahoma who chairs the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, opposes the regulation. He, along with 26 cosponsors, introduced a bill that would specifically put the responsibility for regulating relevant oil and gas operations in the hands of the states rather than the federal government.

In a statement, Inhofe claimed fracking operations have never resulted in any contamination issues:

Inhofe, March 20: Since 1949, my state of Oklahoma has led the way on hydraulic fracturing regulations, and just like the rest of the nation, we have yet to see an instance of ground water contamination.

A spokeswoman for Inhofe, Donelle Harder, told us in an email that “the physical act of cracking rocks through hydraulic fracturing, thousands of feet below ground, has never caused groundwater contamination. What we are not saying is that a surface spill, faulty casing, bad drilling practices cannot be a problem. There is a difference between the hydraulic fracturing process and rest of the well drilling process.”

But scientists we interviewed say that it doesn’t make sense to separate fracking from the entire gas and oil production process, and there is ample evidence that the overall process can cause contamination of water supplies. As we noted above, the new DOI rules cover the entire process including fracking, well casings and other activities.

Well Failures and Water Contamination

Anthony Ingraffea, a Cornell civil and environmental engineering professor, told us in a phone interview that discussing contamination related to the frack per se isn’t useful. “The simpler question to ask is, ‘Is there any instance in which oil and gas development, writ large, has contaminated peoples’ drinking water?’ And the answer is, thousands. Thousands of cases.”

For example, Pennsylvania — which has been at the center of the recent rapid growth in natural gas extraction — maintains a list of hundreds of cases where a “private water supply was impacted by oil and gas activities.” The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection list covers both conventional and unconventional drilling — unconventional gas development refers to drilling for gas in shale and other difficult-to-access geologic formations. But it does not address specifically how the contamination occurred.

Among the first studies specifically linking natural gas development and fracking to water quality was a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2014 that analyzed drinking well water near fracking operations in Texas and Pennsylvania.

In that study, which was coauthored by Jackson at Stanford, researchers identified the presence of methane — the primary component of natural gas — in drinking well water near unconventional drilling sites in the Marcellus Shale region in Pennsylvania and the Barnett Shale region in Texas. Using chemical signatures of certain gases, the researchers were able to determine in several cases that the methane was from deep underground — evidence that the drilling operations had caused the contamination.

The study found that faulty and leaky wells were likely to blame, and recommended studying “whether the large volumes of water and high pressures required for horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing influence well integrity.”

Ingraffea, of Cornell, said sending the water, sand and chemicals down the well puts an enormous amount of pressure on the casing, which could cause it to crack or separate from the steel surrounding it. Many wells are often fracked up to dozens of times, he added, and the repeated increase in pressure could cause failures as well. According to one 2014 paper published in Marine and Petroleum Geology, an estimated 6.3 percent of all Pennsylvania wells drilled between 2005 and 2013 suffered either a “well integrity failure” — meaning failures of barriers including casing, tubing and cement, and actual leakage of gas or fluids into surrounding soil and water — or a “well barrier failure” — meaning failure of one or more barriers with no information indicating actual leakage. The DOI points out that about 90 percent of all new wells are fracked.

Methane has been the primary culprit in proven cases of contamination, but other substances including heavy metals and chemicals related to fracking fluid have been found as well.

A paper published in Environmental Science and Technology in 2013 found higher levels of heavy metals such as selenium and arsenic in wells close to drilling activity in the Barnett Shale region compared with water that was farther from drilling. The researchers concluded that these contaminants could have arrived via a variety of mechanisms, including natural processes or failure of gas well components. Another study found fish kills and damage to other aquatic life following a surface spill of fracking fluid. The fracking process itself was not responsible, but in order to spill fracking fluid at the surface one must intend to frack a well.

Clearly, the DOI’s new regulation is designed to ensure water quality and safety as it relates to the entire process of extracting oil and natural gas, not just to the singular action of fracking. Inhofe is entitled to the opinion that such regulations should be left in the hands of the states, but he is wrong to say or imply that existing regulatory efforts have a perfect track record when it comes to preventing contamination of water supplies.

Update, June 5: The EPA released a draft of its study on fracking’s impacts on water on June 4. It found that fracking has not led to “widespread, systemic impacts” on drinking water, but there have in fact been “specific instances” where fracking did impact drinking water resources, including drinking water wells. That refutes Inhofe’s claim that there have been no instances of contamination.

Editor’s Note: SciCheck is made possible by a grant from the Stanton Foundation.

– Dave Levitan