Sen. Bernie Sanders repeats a Democratic talking point in saying that Social Security hasn’t contributed “one penny” — or “one nickel” — to the deficit. In fact, it contributed $73 billion to the deficit in 2014.

Sanders, an independent who’s running for the Democratic nomination for president, has made this claim several times, recently saying in a video he sent out on Twitter on Oct. 6 that “Social Security does not add one nickel to the deficit.” On Sept. 25, he tweeted that the program “had not contributed one penny to the deficit.” And he, like other Democrats, has been making the claim for several years.

Sanders is talking about what’s called the “on-budget” deficit, while Social Security is considered an “off-budget” program. But in terms of actual federal revenue and outlays, and borrowing, Social Security is contributing to yearly deficits and has been since 2010. Sanders himself has considered Social Security to be a part of the overall budget: On his Senate website, he includes raising the income cap on Social Security taxes as one way to “reduce the deficit.”

“Social Security adds to the unified deficit, which is the deficit we almost all discuss all the time,” Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director at the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, told us in an email interview. “It does so because we spend a lot more on Social Security benefits than we raise in payroll tax and other related revenue.”

Goldwein told us that Sanders’ statement contains a kernel of truth in that Social Security technically can’t run a debt. “That means that any [yearly] deficits it’s running now can only legally be paid because it was running surpluses in the past,” he says. But the government spent the surplus on other things. It owes Social Security the money, which is held in the form of Treasury securities. In order to pay it, the government must cut spending in other areas, raise taxes or borrow from the public.

Because current payroll taxes don’t produce enough revenue to pay Social Security benefits, the program is contributing to the yearly deficits.

Deficits and ‘Off-Budget’ Spending

We wrote about this claim in 2011, when other Democrats made the not-one-penny claim. As we said then, Social Security for years brought in more revenue through payroll taxes than it paid out in benefits, lessening the federal deficit and allowing Congress to spend more money in other areas. But that changed in 2010, when benefits paid outpaced revenues generated.

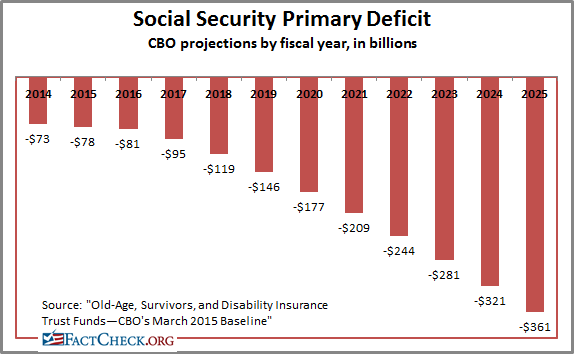

That year, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said Social Security had a $37 billion primary deficit and projected a $30 billion deficit in 2014. The deficit actually was $73 billion in 2014, says CBO, which now estimates that the yearly deficit will rise to $177 billion in 2020 and $361 billion in 2025. (The “primary deficit” is the total budget deficit excluding interest payments.) CBO expects outlays to continue to rise, compared with the size of the economy, as baby boomers retire and retirees live longer, but tax revenues “will remain at an almost constant share of the economy.”

CBO’s projections show that Social Security’s balance is expected to grow for several years, but that’s because Treasury must credit the trust funds with interest payments on past borrowing. The government will have to either increase taxes, cut spending or borrow from the public to pay that interest that it owes to itself.

This doesn’t mean that Social Security benefits are in danger, at least not in the next few decades. The government can make up that gap between Social Security revenues and outlays with the Social Security trust funds, essentially cashing in Treasury bonds it holds for that amount or using interest paid on those bonds. The Trustees of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds’ most recent report says: “Interest income and redemption of trust fund assets from the General Fund of the Treasury, will provide the resources needed to offset Social Security’s annual aggregate cash-flow deficits until 2034.” At that point, the trust fund would be exhausted. CBO estimated the trust fund would be depleted earlier, in 2029.

Once the trust fund is gone, Social Security can still pay benefits — but not more benefits than it takes in from revenue. The trustees say tax income would be able to cover three-quarters of the benefits through 2089.

Sanders, and other Democrats, claim that Social Security doesn’t add to the deficit, because it still has that trust fund to make up the financing gap. Sanders said in his video: “Social Security has a $2.8 trillion surplus and according to the Social Security Administration can pay out every benefit owed to every eligible American for the next 19 years. … Social Security is independently funded by the payroll tax … that means that Social Security does not add one nickel to the deficit.”

That’s correct in theory, but not in practice. “Politicians decided to classify Social Security and the postal service as ‘off budget’ so that they would be treated as their own programs and not as part of the government,” Goldwein says. “It didn’t work. Everyone uses the unified budget deficit concept.”

That includes Sanders, who, Goldwein points out, listed raising the income cap on Social Security taxes as one way to “reduce the deficit” and said in a 2013 press release that 2009’s $1.4 trillion deficit was on track to be reduced by more than half — that’s the total, unified deficit. And in a speech in March, Sanders said: “From 1998-2001, the budget was in surplus.” But the “on-budget” surpluses only occurred in 1999 and 2000. The U.S. government had budget surpluses for all four of those years, because the “budget” is the total budget. (See Table H-1 of this CBO report.)

When politicians, economists and experts like the Congressional Budget Office talk about the “deficit,” they’re talking about the combined effect of all government revenues and spending. As the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center says: “Despite the formal separation of Social Security from the rest of the budget, budget debates in Congress and the media focus mainly on the unified budget balance, that is, the combined balance of Social Security and the rest of government.”

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget says that even if Social Security is viewed as an “off-budget program,” it still indirectly adds to the on-budget deficit.

CRFB, Aug. 13, 2015: If viewed as an off-budget program, Social Security does not directly add to the “on-budget deficit.” However, it indirectly contributes to the on-budget deficit because the interest payments it receives from the general fund are on-budget. It also receives funding from income tax revenue on Social Security benefits, which is technically on-budget, and has at times received general revenue transfers to compensate for policies that would reduce Social Security revenue (such as when lawmakers cut payroll taxes in 2011 and 2012).

For years, Social Security was a boon to the government’s bottom line, lowering the deficit and even causing a budget surplus in 1998 and 2001. But now outlays outpace revenues, and the government has to use deficit spending to honor its obligations to the program.

CRFB issued a report in August, marking the 80th birthday of Social Security and identifying several common falsehoods about the program. It says it’s a “myth” that “Social Security cannot run a deficit.” We agree.

— Lori Robertson, with Raymond McCormack