Democrats and Republicans are pointing fingers over an increase in illegal immigration at the southern border, and notably an increase in children traveling alone.

While Democrats argue the surge began before President Joe Biden took office, Republicans argue Biden’s welcoming policies are to blame. A rise in border apprehensions did begin prior to the election under then-President Donald Trump. But the increase in unaccompanied children has spiked significantly in the first full month of the Biden administration.

The unaccompanied children are being held in custody in large numbers while the administration tries to catch up with a backlog in housing and processing them.

We’ll take a look at the immigration statistics and facts behind the recent increase.

How many people are trying to cross the border illegally?

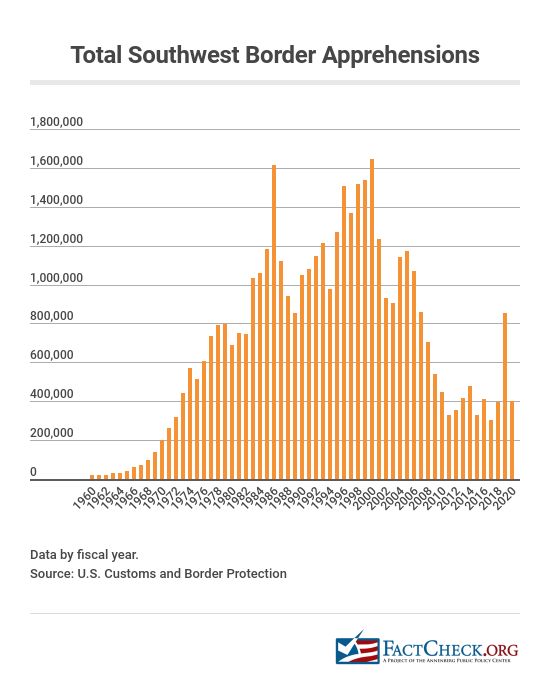

Let’s start with a look at the big picture: Apprehensions on the southwest border peaked in 2000 at 1.64 million and have generally declined since, with some fluctuations. In 2017, apprehensions hit the lowest level since 1972, but they spiked in fiscal year 2019 at 851,508 and fell back down to 400,651 in fiscal 2020.

On a monthly basis over the past year, apprehensions plummeted to 16,182 in April 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic and economic shutdowns gripped both the U.S. and Mexico. But then, apprehensions started ticking up again, increasing noticeably in late summer and fall. By October, 69,022 people were apprehended on the southwest border, up 79% from July. In February, the figure was 96,974.

While the bulk of the increase comes from single adults, the number of children arriving at the border without an adult has gone up as well. Here’s a breakdown of the type of apprehensions by month — for single adults, unaccompanied children and those traveling in a family unit — dating back to 2013, the earliest point of data for family units.

Tony Payan, director of the Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, wrote in a March 15 blog post that “the current situation at the border is neither a unique crisis nor the result (yet) of Biden’s policy changes.”

In a phone interview, he told us that while the apprehension numbers are spiking now, “this is not a new crisis.” Instead, it has been going on since 2014, “when we first saw unaccompanied minors and family units arriving at the border and turning themselves in,” and the problem has plagued each administration since.

As the chart above shows, apprehension spikes under the past two presidents in 2014 and 2019 similarly included sizable increases in family units and unaccompanied children arriving at the border.

Other immigration experts, writing in the Washington Post, agree that “the current increase in apprehensions fits a predictable pattern of seasonal changes in undocumented immigration combined with a backlog of demand because of 2020’s coronavirus border closure.” It’s “not a surge,” they said.

Overall, Payan said, “The patterns of migration do not seem to correlate to any specific U.S. immigration policy. The numbers seem to go up and down on a logic of their own.” People leave their home countries for reasons other than U.S. policy, such as deteriorating economic, political or public safety conditions.

How does this increase in unaccompanied children crossing the border compare with past increases?

The recent numbers are on track to rival or surpass the spike of unaccompanied children apprehended in 2019.

A report from the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service sums up the trends in what the government calls UAC — “unaccompanied alien children” — this way: “In FY2014, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Customs and Border Protection (CBP) apprehended 68,541 UAC, a record at that time. Since FY2014, UAC apprehensions have fluctuated considerably, declining to 39,970 in FY2015, increasing to 59,692 in FY2016, declining to 41,435 in FY2017, and increasing to 50,036 in FY2018.”

In fiscal year 2019, the number of unaccompanied children who were apprehended — 76,020 — surpassed 2014’s total, a new yearly record. And in fiscal 2020, which ended on Sept. 30, the total dropped considerably to 30,557.

At just five months into this fiscal year, the number is already at 29,010. The number of unaccompanied children being apprehended at the southern border did start trending up in October, but also jumped 63% from January to February, when the total was 9,297.

As Payan said, the issue started in 2014, and it has been a problem for each administration.

Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told us that 2014 was not only the first time there was a dramatic increase in unaccompanied children, but migrants also came from Central America, not Mexico.

“The border facilities and the system of processing unaccompanied minors under law were designed for the time when the vast majority of encounters at the border were single adult Mexican males who were processed and returned across the border very quickly, often within a day,” Brown said in an email. “But Central Americans could not be sent back across to Mexico and if they applied for asylum, or were UACs would have to be taken into custody and provided an opportunity to make their case in immigration court.”

Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, said the increases of families and unaccompanied children in 2014 and 2019 “overwhelmed U.S. resources.” In both of those years, the flow of immigrants “were driven primarily by longstanding push and pull factors.”

Those “push and pull factors” include poverty and violence in migrants’ home countries, and economic opportunity in the U.S., family ties and border policies on children and families, as the Migration Policy Institute outlined in a 2019 report.

In 2019, another factor was a “chaotic implementation of restrictive southern border policies” under Trump, Pierce told us.

The difference this year is that the increase overwhelming U.S. resources “has been entirely driven by unaccompanied child migrants,” Pierce said. The flow is also due to push and pull factors, as well as the coronavirus pandemic-caused economic crisis and recent hurricanes.

All three experts we spoke with told us there may be a perception that the Biden administration is more welcoming to migrants, but “Biden has not significantly changed operations at the border since Trump as of yet,” as Brown said.

In mid-February, the administration announced it would begin processing non-Mexican asylum seekers who have been waiting in Mexico for their U.S. court dates under a Trump-era program to keep those individuals on the other side of the border. But that policy doesn’t concern new arrivals or those without pending asylum cases, the administration said.

One notable change for unaccompanied children, however, is that they are “the only population that is officially exempt from the CDC’s Title 42 order,” Pierce said.

What is Title 42 and how has it affected immigration flows?

Title 42 is a public health law the Trump administration began invoking in March 2020 to immediately expel, due to the coronavirus pandemic, those apprehended on the southern border. In November, a federal judge ordered a halt to such deportations of minors. While the Biden administration has continued to use the law to expel adults and some families, it has stopped expelling children.

“We are expelling most single adults and families,” Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said in a March 16 statement. “We are not expelling unaccompanied children.”

While that’s certainly the case for single adults, CBP data show, the administration expelled 41% of family units in February, down from 62% who were expelled in January. The Washington Post wrote about the discrepancy.

Brown noted that migration started to increase in April 2020 and “continued to rise through the Biden inauguration. So it is not true that the increase started under Biden.” But the decision not to expel unaccompanied children “sped up the increase.”

“A somewhat new phenomenon, being reported by attorneys for migrants in the region, is that it seems that some unaccompanied children actually arrived in Northern Mexico with family members who sent them into the US alone since the U.S. was letting them in, and then the adults would try to come in later,” she said.

At the same time, Title 42 may have artificially inflated the problem of single adults being apprehended, because some are trying to cross repeatedly in short time frames.

“We know that single adults have driven the majority of the total increase in encounters at the border,” Brown said in an email. “But we also have been told by CBP that as many as 1/3 of those are repeat encounters with the same person. We believe that because Title 42 results in rapid expulsion of migrants back to Mexico within a very short period of time, and no immigration process (and therefore no immigration bars being applied), the opportunity cost of migrants to repeatedly try to cross the border is low.”

Brown said there are reports that smuggling operations “are charging rates for ‘up to 3 attempts.'”

The increase in single adults also could be due to people sending children ahead of them and attempting to follow separately. “But there are not detailed statistics on that,” she told us.

What’s the process for these unaccompanied kids? How many unaccompanied children are being held in Customs and Border Protection custody?

Unaccompanied children are generally referred to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement. Some from Mexico can be returned home, a Congressional Research Service report explains, but the vast majority of these kids in recent years are from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. While that referral process is taking place, they are held in Customs and Border Protection custody.

A backlog, due to the increase in unaccompanied children arriving at the border and policies in place due to the coronavirus pandemic, has led to a crush of kids being held in border facilities. One lawmaker released images of kids sleeping on cots on the floor.

A CBP spokesperson wouldn’t tell us how many children are now in custody, saying that it doesn’t provide daily numbers “as they are considered operationally sensitive because CBP’s in-custody numbers fluctuate on a constant basis. The number it shares one morning may be different by the afternoon and the next day.”

CNN reported on March 20 that more than 5,000 unaccompanied children were in CBP custody, “according to documents obtained by CNN, up from 4,500 children days earlier.”

The children are only supposed to be in CBP custody for up to 72 hours, before being transferred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement. CNN reported that the children were being held an average of five days and that more than 600 of them had been held in CBP custody for more than 10 days.

“Unfortunately HHS waited until March 5 to start bringing beds back that were taken offline during the pandemic,” Pierce told us of the problem. “While HHS is making efforts to expand their capacity by bringing these beds back online and acquire new influx facilities, their lack of bed space has led to the current back up of children in CBP custody.”

The CBP spokesperson told us the agency’s “ability to move children out of its care is directly tied to available space at HHS ORR” and that “everybody’s focus is on moving UACs through as quickly as we can.”

Past administrations have also struggled to get unaccompanied minors out of CBP custody.

In a November 2019 report, for instance, the Department of Homeland Security wrote: “One of the most visible and troubling aspects of this humanitarian crisis, one that manifested itself in April, May and early June 2019, was young children (sometimes for a week or more) being held by CBP’s Border Patrol, not because it wanted to hold them, but because HHS had run out of funds to house them.”

A July 2019 DHS Office of Inspector General report warned of “dangerous overcrowding” of kids held in five border facilities. It said CBP data showed 2,669 children, some who arrived at the border alone and some with families, had been held for more than 72 hours, with some children younger than 7 years old held for more than two weeks.

Once with the Office of Refugee Resettlement, children stay in shelters while awaiting immigration proceedings, including asylum, before being placed with a sponsor, who could be a parent, another relative or a non-family member. In fiscal year 2019, 69,488 children were referred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which has cared for 409,550 children since 2003. The HHS press office told us there are currently about 11,350 children in ORR care.

Data from HHS from fiscal year 2012 through 2020 show that at least 66% of referred children each year have been male. They are primarily from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, and most are age 15 and older.

The Biden administration has tasked the Federal Emergency Management Agency with assisting HHS in housing the children.

Update, March 23: We updated this story with the number of children now in the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.