The demand for at-home, rapid COVID-19 tests — sparked by the fast-spreading omicron variant in December — has continued in 2022. With that demand have come questions about the tests’ efficacy, how to use them and where to get them. We answer those queries and more.

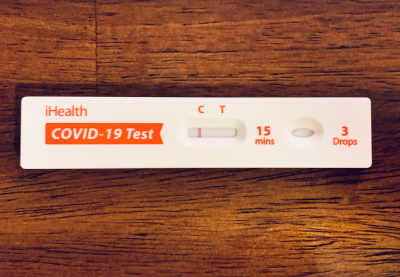

We focus on the fully at-home antigen tests, which provide results in about 15 minutes. President Joe Biden has said his administration will provide 1 billion free at-home tests to Americans, beginning Jan. 19.

What is a rapid antigen test?

Antigen tests are viral tests that check for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins in a sample from a person’s nose or mouth to help determine if the person is currently infected with the coronavirus.

Some of these require a prescription, but the ones people are most familiar with are the self tests that can be purchased over-the-counter and can be performed entirely at home, with a person taking their own sample, running the test, and reading out the result within 15 to 30 minutes.

Some of these require a prescription, but the ones people are most familiar with are the self tests that can be purchased over-the-counter and can be performed entirely at home, with a person taking their own sample, running the test, and reading out the result within 15 to 30 minutes.

Sometimes known as lateral flow tests or lateral flow devices, rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 are similar to pregnancy tests in that they detect proteins in a specimen using antibodies embedded in a test strip. Typically, COVID-19 rapid tests use antibodies that recognize parts of the nucleocapsid, or N, protein of SARS-CoV-2 because more of that protein is made and because it’s less likely to change over time as the virus mutates.

Indeed, in the case of the omicron variant, the majority of the mutations are in the gene that encodes the spike, or S, protein, which is the protein that is used in vaccines to prime the immune system and protect against disease. Compared with previous variants, the omicron variant’s N protein is relatively unaltered, differing by a single short deletion and sometimes, one additional change.

What at-home antigen tests had been authorized by the FDA when Biden took office?

Biden has repeatedly mentioned the increase in the availability of at-home, over-the-counter tests under his administration, saying, as he did on Dec. 27: “For over-the-counter, at-home test, as I said, there — there were none when we took office. None. Now we have eight on the market. And just three days ago, another test was cleared.” Although one over-the-counter, fully at-home test had received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration on Dec. 15, 2020 — a month before Biden took office — it wasn’t “on the market,” meaning in retail stores and available for purchase, until April, well after Biden became president.

The Ellume COVID-19 Home Test was the “first over-the-counter (OTC) fully at-home diagnostic test for COVID-19” authorized by the FDA, the agency’s press release in December said. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have paid Ellume to develop and manufacture the test. The company received $30 million from the National Institutes of Health in 2020 to speed up development of its antigen tests, and in February, the Biden administration made a deal to pay $231.8 million for Ellume to manufacture the at-home tests and to help fund construction of a manufacturing plant in the U.S.

A spokesperson for Ellume, a medical technology company headquartered in Australia, told us the tests were first available for sale to consumers at CVS Pharmacy, starting with some locations in Rhode Island and Massachusetts in mid-April and expanding to most CVS stores by the end of May. Also in mid-April, some CVS stores began selling another at-home test from Abbott that had received FDA authorization on March 31.

“As of November 2021, Ellume had shipped approximately 3.5 million test kits to the U.S.,” spokesperson Annalyse Keller told us in an email. However, 2.2 million of those were subject to a recall because of “higher-than-acceptable false positive test results,” according to the FDA.

Before Biden took office, the FDA had authorized another at-home antigen test, but it required a prescription (the BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card Home Test, authorized on Dec. 16, 2020).

The National Institutes of Health launched the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative in April 2020 with $1.5 billion in federal funding to speed the development of rapid COVID-19 testing. On Oct. 25, NIH announced it would spend $70 million to launch an Independent Test Assessment Program, an extension of RADx, to “help identify manufacturers of high quality tests and encourage them to bring those tests to the U.S. market.”

What has FDA authorization now?

Thirteen fully at-home, over-the-counter antigen tests now have FDA authorization. The Biden administration told us last month that eight of them are on the market.

There are three other at-home antigen tests that require a prescription and have FDA authorization.

The Biden administration has invested billions to increase production of rapid tests. Dawn O’Connell, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services, said in a Jan. 11 congressional hearing that the administration invested $3 billion in the fall “to increase manufacturing line staffing” of rapid, over-the-counter tests and “commit to those manufacturing lines for 13 months.”

“As a result, we went from 46 million tests, over-the-counter tests, available in October to the 300 million … that are available now,” O’Connell said. “But that’s not enough.”

The Kaiser Family Foundation noted in a Nov. 4 report on the availability of these tests that even reaching 300 million per month would be “less than one test per month per person in the U.S.”

How accurate are rapid antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection?

Antigen tests are generally reliable, but they aren’t as sensitive as molecular diagnostic tests, such as polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, tests. Compared with those tests, antigen tests are more likely to fail to register a coronavirus infection, resulting in a false negative reading.

To a lesser extent, antigen tests are also less specific than molecular tests, incorrectly flagging some people as being positive when they aren’t infected, and showing what’s known as a false positive. These performance features, however, are expected — and are a trade-off for having a test that can return a result in minutes rather than hours or days.

Collectively, this means that a positive result on an antigen test is very likely to be correct, but a negative test doesn’t necessarily mean someone is in the clear.

Antigen tests are also more accurate in people with symptoms compared with someone who does not have symptoms.

Minimum standards have been set for these tests. FDA guidance, for example, calls for a minimum sensitivity of 80%, or fewer than 20% false negatives, and a minimum specificity of 98%, or fewer than 2% false positives, for tests that receive emergency use authorization. The World Health Organization recommends the same minimum sensitivity measure and at least 97% specificity, relative to a molecular test, when testing those with suspected COVID-19.

It’s important for consumers to recognize that not all tests for sale have received FDA-authorization and some may not work well; the agency has warned about some of these unauthorized products.

Even among tests that have received some kind of vetting by a regulatory agency, quality can vary, as a test that detects 80% of those who are positive is very different from one that detects 95% or more.

These sensitivity and specificity figures, which come from evaluations that companies submit to the FDA, do not necessarily apply to the latest versions of the coronavirus in circulation. The FDA, however, is requiring test manufacturers to monitor for changes in their tests’ performance against new variants, which must be reported to the agency.

How do rapid antigen tests perform against omicron?

It is not yet known how well rapid antigen tests fare against omicron, although most tests are able to detect the variant. Based on how the tests work — by checking for the presence of a SARS-CoV-2 protein, typically the nucleocapsid protein — the omicron variant is generally not expected to render tests less effective, as the variant has few changes to the nucleocapsid protein. But there are some indications that omicron may pose additional challenges for the tests.

Anecdotally, there are reports that with the arrival of the omicron variant, more rapid antigen tests are turning up falsely negative in people who have recently started to have symptoms. Melissa Miller, the director of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine’s clinical microbiology lab, told us that she was seeing such false negatives “quite a bit in the community.”

Some preliminary evaluations have suggested that some tests may be less capable of picking up the omicron variant, but it’s not yet clear whether those have any clinical relevance — and other studies have not found such deficits.

An unpublished and yet-to-be peer-reviewed study of rapid antigen tests posted on Dec. 22 by scientists in Switzerland found a “tendency towards lower sensitivity” for the omicron variant, compared with previous versions of the virus. The researchers evaluated seven rapid antigen tests, three of them listed for emergency use by the WHO, using cultured viruses.

The authors cautioned that if their findings were confirmed with clinical evaluations — an important step — rapid antigen tests “could be less reliable” against omicron when used in people without symptoms or when symptoms have just begun.

U.S. government agencies have also hinted at a possible reduction in sensitivity, although this remains inconclusive. On Dec. 28, the FDA wrote on its website, “Early data suggests that antigen tests do detect the omicron variant but may have reduced sensitivity,” referring to preliminary lab studies performed by the National Institutes of Health’s RADx program that used patient samples containing live virus. Earlier lab tests, with heat-inactivated patient samples, found no difference in performance against omicron compared with other variants.

In an email, Bruce J. Tromberg, director of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and lead for the RADx Tech program, told us that the tests suggesting reduced sensitivity were “of a few major tests using our first serial dilution pool of omicron” and that his group was in the process of repeating the evaluation “with more sample pools and a wider representation of patients.”

But he also cautioned that lab tests are just one consideration. “The gold standard and most important evaluation is clinical testing of a large number of patients,” he said, adding that those studies are ongoing at Emory University and other program-supported sites. So far, he said, those results show antigen tests perform similarly against omicron as previous variants, “though the time course and ‘window’ may be more compressed” for omicron.

As Tromberg explained in more detail to the website 360Dx, these contradictory results might reflect differences in when the patient samples are taken, since it’s known the amount of N protein relative to the amount of RNA can change over time during an infection. Omicron infections appear to have a shorter incubation period, or length of time from exposure to first symptom, which could mean people are testing sooner after infection than they were previously. That could make it appear that the tests are less sensitive, even if they aren’t — but it would still complicate the use of rapid tests in the omicron-era.

“The rapid antigen tests likely detect the same amount of virus between Omicron and Delta,” UNC’s Miller told us in an email, “but the difference is how quickly symptoms occur with Omicron (~3d) which is more quickly than with Delta (5-7d). Therefore, it is possible that the viral quantities at day1 of symptoms with Omicron are less than Delta, which could impact antigen sensitivity and be a false negative test.”

In any case, if people infected with omicron become contagious more quickly than with delta, there’s less time for a test to intervene and make people aware that they are likely infectious, which limits some of the public health utility of rapid testing, as experts have told the Atlantic.

Tromberg noted that other groups in addition to his are reporting results from the clinical studies, including an unpublished paper evaluating Abbott Laboratories’ popular BinaxNOW antigen test. In that study, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested 731 people at a walk-up testing site in San Francisco in early January with a BinaxNOW test and also collected a second nasal swab to run a PCR test. Sequencing of a random sample of the samples that were positive showed the vast majority — 97% — were infected with the omicron variant. The rapid test identified 95.2% of the positives found by PCR that had the highest levels of virus in the sample, 82.1% of those with lower levels, and 65.2% with the lowest; the test also correctly identified 89.8% of people who did not have symptoms and 97.6% of people with symptoms.

“This work in a large population suggests there is not diminished performance” of the Abbott test against omicron, Tromberg said, but that it “emphasizes the value of sequential/serial testing,” which is the way most rapid antigen tests are designed to be used. “A single negative test result for those who are asymptomatic has always been ‘presumed negative’ (regardless of variant) and should be repeated,” he added. “A positive test result with symptoms is a good measure of infection and likely infectiousness.”

For its part, Abbott told us it has “completed extensive testing” on cultured omicron viruses in the lab as well as on 74 clinical samples from patients infected with omicron. “In all cases, our studies confirm that BinaxNOW continues to detect the Omicron variant at comparable viral load levels as all other variants and the original SARS-CoV-2 strain,” the company said. Abbott also pointed to the unpublished study in San Francisco, with which it was not involved and which found its test worked well against omicron.

Another unpublished study that has received attention is a small evaluation comparing antigen and PCR test results in 30 people who were being tested daily in December 2021, most of whom were likely infected with the omicron variant. The paper, which has not been peer-reviewed, found that two common rapid tests, Abbott’s BinaxNOW and Quidel’s QuickVue, often failed to detect infection for a few days after a saliva PCR test came back positive, even though most people were likely infectious at the time of the test.

Although it has been sometimes interpreted to mean that the omicron variant is more difficult to detect than previous variants, the paper did not directly compare variants. Another difference between the tests was the sample type used. Some scientists have suggested that the omicron variant might be easier to detect from saliva or a throat swab rather than a nasal swab, given early evidence that the virus replicates better in the bronchus –the airway leading from the windpipe to the lung — than the delta variant.

“The important take-home message is that when the virus is present at low levels – which may be the case very early on after infection – the antigen tests may be negative,” Matthew Binnicker, director of clinical virology at the Mayo Clinic, told us when asked about the confusing omicron data. “As the virus increases in amount, typically by days 3 or 4 following infection, then most of the antigen tests should be able to detect the virus.”

How should people use rapid antigen tests?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers rapid tests one of several “risk-reduction measures” that can reduce the risk of spreading the coronavirus to others. The agency says they can be used whether or not you have been vaccinated or have symptoms, and suggests considering them “before joining indoor gatherings with others who are not in your household.”

If the test is positive, you are “very likely” to be infected, the agency says, and should isolate for at least five days, followed by another five days of always wearing a well-fitting mask when around others and avoiding travel.

“If a person is symptomatic and has a positive antigen test from a nasal swab, they can feel comfortable that this is an accurate result. They do not need to get a follow up PCR to confirm at the current rates of infection we are seeing,” UNC’s Miller told us.

But the opposite is not true for someone who tests negative. If symptoms have just started, Miller said, you should assume you are infected until proven otherwise — either with a PCR test or doing repeated antigen tests over a few days.

The timing also matters — and may be especially important for omicron infections. Performing the antigen test too soon, such as the day after an exposure, Binnicker said, could result in a false negative simply because there hasn’t been enough time for enough virus to build up in the body.

At the same time, Tromberg told 360Dx that with omicron, there appears to be a smaller window in which infected people test positive on antigen tests, so it’s also important not to wait too long. He recommended people test “within one to two days of a known or suspected exposure.” Again, if a test is negative, it should be repeated in a day or two to be confident in the result.

Controversially, the CDC has said that you do not need to take a rapid test to end isolation, but if you do use one and test positive after five days, you should continue to isolate for another five days.

Miller said it would be safer to require a negative antigen test before exiting isolation, since her data shows that at day five, about 80% of people would still be antigen-positive. But the guidance reflects practicalities.

“Unfortunately, staffing shortages throughout multiple industries don’t allow for this luxury. In light of the constraints, at 5d a person should be asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic and improving (no fever, no cough) and religiously wear a mask,” preferably a better N95 or KN95, she said. “If people can stay home and isolate for 10d or work from home, they should.”

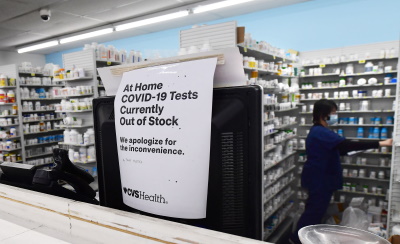

Where can people get at-home tests?

While demand has been high — and, therefore, supply low — retail stores carry at-home tests, and sell them online. There’s Amazon, too, and Abbott tests are sold through emed.com, which noted as recently as Jan. 14 that it was “experiencing heightened demand” and test kits could be delayed for a week.

Beginning Jan. 15, the federal government is requiring private health insurance plans to cover the cost, either at the point of sale through preferred pharmacies or retailers, or through reimbursement, for up to eight tests per person per month. About 55% of Americans have private insurance.

If an insurer sets up a system to cover the cost at preferred stores, it must reimburse up to $12 per test if a policyholder purchases tests at a different retailer. And insurers that don’t have a system to cover costs at the point of sale must reimburse the full cost.

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program must cover the cost of at-home tests, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services says. Medicare covers laboratory COVID-19 tests, and Medicare Advantage plans might cover at-home tests.

Some local governments are also offering free at-home test kits. For instance, Washington, D.C., is distributing them to residents through city libraries. The Department of Health and Human Services says it is giving community health centers and Medicare-certified clinics up to 50 million at-home tests to distribute.

When is the administration going to ship tests to every person in the country who wants one?

The Biden administration announced on Dec. 21 that it would buy 500 million at-home tests to be sent to any American who requested one, and on Jan. 13, Biden said the federal government would increase that to 1 billion. But the first of those tests won’t be shipped until the end of January, and the administration expects it would take another 60 days after that to get the rest of the initial half billion tests out to the public, according to the Jan. 11 congressional testimony by the Department of Health and Human Services’ O’Connell.

The government began awarding contracts to manufacturers in early January. O’Connell said the administration had “secured 50 million tests” and completed four contracts as of Jan. 11.

Administration officials said a new website — COVIDTests.gov — is supposed to be operational on Jan. 19, allowing Americans to request the tests, which will be sent through the U.S. Postal Service within seven to 12 days of being ordered.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over our editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.