Quick Take

Wastewater surveillance is a public health tool that can track the spread of pathogens. The virus that causes polio was detected in New York City sewage as part of such monitoring efforts. Social media posts, however, have incorrectly claimed the virus was found in tap water. Similar claims have been made about the monkeypox virus.

Full Story

Health officials announced on Aug. 12 that poliovirus, the virus that causes the paralytic disease polio, was identified in sewage from New York City, indicating the virus is circulating there and people who are not fully vaccinated against polio could be at risk.

While the virus was detected in wastewater as part of surveillance, people on social media are falsely saying that it was found in tap water.

Many of these claims focus around New York City Mayor Eric Adams, who in July promoted the city’s tap water in videos posted to his TikTok and Twitter accounts.

“Do you remember that time when Mayor Adam’s told everyone in New York City to drink the tap water? Anyways, they found Polio in the New York City Water,” reads one Instagram post that includes Adams’ original video.

One version of the post — an Aug. 13 reshare — accumulated more than 100,000 likes in under three days. “Under Biden, they are now finding Polio in tap water,” the caption reads. “Congratulations, your vote has put us in a third world state all because you don’t like ‘mean tweets.’”

One version of the post — an Aug. 13 reshare — accumulated more than 100,000 likes in under three days. “Under Biden, they are now finding Polio in tap water,” the caption reads. “Congratulations, your vote has put us in a third world state all because you don’t like ‘mean tweets.’”

The original post comes from an account that has previously shared misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines and the 2020 election. Other posts on Facebook have also falsely claimed that poliovirus was found in New York City’s drinking water.

As we’ve said, these posts are incorrectly conflating tap water with wastewater.

Wastewater, or sewage, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says, “includes water from household or building use (such as toilets, showers, and sinks) that can contain human fecal waste, as well as water from non-household sources (such as rain and industrial use).”

“Polio surveillance was conducted on sewage. NOT tap water,” New York City health department spokesperson Patrick Gallahue told us in an email. “Tap water is safe,” he added. “PEOPLE CANNOT GET POLIO BY DRINKING TAP WATER IN NYC.”

Ted Timbers, communications director of the city’s department of environmental protection, also reassured the public about the safety of the city’s drinking water.

“NYC tap water is tested more than half a million (556,000 times) times annually to ensure it is of the highest quality – NYC tap water is absolutely safe to drink,” he told us in an email.

Wastewater Surveillance for Polio

State officials in New York began testing sewage samples, including previously collected samples, for poliovirus after a rare case of polio was identified in Rockland County — a county just north of New York City — on July 21, a state webpage explains.

The affected individual was an unvaccinated young adult who developed weakness and paralysis in mid-June after infection with a vaccine-derived strain of poliovirus.

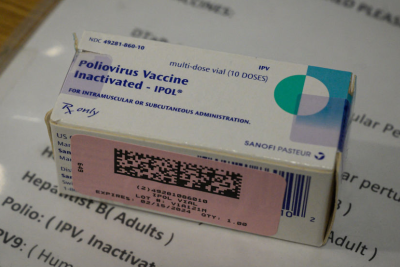

Since 2000, the U.S. has only used the inactivated polio vaccine, which does not contain any live virus and cannot give someone polio. Other countries, however, still use the live attenuated oral vaccine, since it can prevent onward transmission and is better for eradication efforts.

On rare occasions, however, the vaccine virus can replicate in an immunocompromised person or in a larger population and revert back to a virus that can cause paralysis. When this happens, usually after a year or more of circulation, unvaccinated people are at risk of developing polio.

Because the Rockland individual didn’t recently travel internationally, it suggests that there was a chain of transmission within the U.S. that originated with someone who was vaccinated abroad with the oral polio vaccine. Genetic analysis of the person’s poliovirus, which has 10 differences from a vaccine strain, the CDC notes, indicates up to a year of circulation, although the location of that transmission is unknown.

The Rockland polio case was the first in the U.S. since 2013, which occurred in an immunocompromised baby who was given the oral polio vaccine in India — and the first instance of a chain of transmission in America since 2005.

Wastewater surveillance, which has become a more developed public health tool during the COVID-19 pandemic, is useful because it can track the spread of a disease in a community in an anonymous way that’s not dependent on testing or a person identifying symptoms.

That’s important for polio because most people who are infected with the virus don’t have any symptoms. A quarter of people will develop flu-like symptoms, and only a much smaller proportion of people develop more severe symptoms, such as meningitis or paralysis. Paralysis, which can be deadly, occurs in one in 200 people or less, depending on the viral strain (including about one in 1,900 people for the vaccine-derived strain identified in the Rockland case). Only people who develop paralysis are said to have polio.

Per the New York State Department of Health, as of Aug. 12, 20 sewage samples have been genetically linked to the virus identified in the Rockland County polio case, including 13 collected from May through July in the county, as well as seven collected in June or July in neighboring Orange County.

Six other samples from New York City — two in June and four in July — were positive for poliovirus. It is not known yet whether those are also genetically linked to the Rockland County case, but they were a vaccine-derived poliovirus strain.

The wastewater findings are important because they suggest that local transmission of poliovirus is occurring — and underscore the need for people to get vaccinated against the disease.

Polio Vaccination

Most adults in the U.S. were vaccinated against polio as children, but some may have skipped immunization or not be fully vaccinated.

According to the CDC, children should get four doses of the vaccine — three doses by 6 through 18 months of age and a fourth dose between 4 through 6 years of age. Three doses of the inactivated polio vaccine are at least 99% effective in preventing polio.

In New York City, only 86.2% of kids 6 months to 5 years of age having received three doses of the vaccine as of this June. In some zip codes, the rate is below 60%.

At around 60% or lower, Rockland and Orange Counties have below-average rates of kids having received three doses of the polio vaccine by 2 years of age. Rockland County is where a measles outbreak occurred in 2018 and 2019, primarily among unvaccinated individuals in the Orthodox Jewish community, which had low measles vaccination rates.

Polio is highly contagious and is spread through contact with feces and to a lesser extent, through infectious droplets from sneezes or coughs.

But polio’s connection to sanitation — as the caption of one of the posts indicates (“anyone who knows the true history of ‘Polio’ knows the correlation it has to sanitation”) — is widely misunderstood.

As we’ve explained before, polio is no longer usually a problem in the U.S. because of vaccination, not improved sanitation. Better sanitation, in fact, made polio more visible in the middle of the last century because before 1910 or so, most people got infected with polio very young, when the risk of paralysis was very low. The threat of the disease was largely eliminated only after widespread vaccination.

Similar Monkeypox Claim

In addition to polio, people on social media have also misinterpreted news of wastewater surveillance for monkeypox virus to mean that that virus was found in drinking water.

An Aug. 8 Facebook post, for example, shares a clip of someone commenting while recording a local news story about a wastewater facility near Atlanta, Georgia, beginning to do surveillance for monkeypox virus.

“They have found monkeypox in the Water,” the post reads, incorrectly implying that the news is concerning and applies to drinking water.

The local news report, however, which was from July 26, didn’t even report that monkeypox virus had been detected in wastewater. It was simply reporting that testing for the virus — in sewage samples — was starting.

“The testing is on WASTEWATER,” Patrick Person, the water quality manager with Fulton County, Georgia, told our fact-checking colleagues at Reuters, when asked about similar posts. “The social media clip you are referring to is false and misleading. Again, we are testing WASTEWATER … The drinking water is 100% safe.”

Earlier this year, we also debunked an elaborate conspiracy theory that incorrectly posited that COVID-19 was caused not by a virus, but by snake venom being spread to the population through drinking water. The supposed link to the water system was the fact that the CDC was helping facilitate wastewater surveillance for COVID-19.

FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Sources

“NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH Wastewater Monitoring Identifies Polio in New York City and Urge Unvaccinated New Yorkers to Get Vaccinated Now.” Press release. NYC Health. 12 Aug 2022.

“National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS).” CDC. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Gallahue, Patrick. New York City health department spokesperson. Email sent to FactCheck.org. 16 Aug 2022.

Timbers, Tim. Communications director, New York City department of environmental protection. Email sent to FactCheck.org. 16 Aug 2022.

“New York State Department of Health and Rockland County Department of Health Alert the Public to A Case of Polio In the County.” Press release. New York State Department of Health. 21 Jul 2022.

“Wastewater Surveillance.” New York State Department of Health. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Link-Gelles, Ruth et al. “Public Health Response to a Case of Paralytic Poliomyelitis in an Unvaccinated Person and Detection of Poliovirus in Wastewater — New York, June–August 2022.” MMWR. 16 Aug 2022.

McKinley, Jesse and Nate Schweber. “Rare Case of Polio Prompts Alarm and an Urgent Investigation in New York.” New York Times. 22 Jul 2022.

“Oral poliovirus vaccine.” Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

“Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus.” CDC. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

“Wastewater Surveillance in NYS.” New York State Department of Health. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

“What is Polio?” CDC. Updated 11 Aug 2022.

Branswell, Helen. “Wastewater monitoring identifies polioviruses in New York City.” STAT. 12 Aug 2022.

“Polio Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know.” CDC. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

“Polio Vaccine Effectiveness and Duration of Protection.” CDC. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

“Polio Vaccination Coverage With Three Doses, by New York City Modified ZIP Code Tabulation Areas.” NYC.gov. 28 Jul 2022.

McDonald, Robert et al. “Notes from the Field: Measles Outbreaks from Imported Cases in Orthodox Jewish Communities — New York and New Jersey, 2018–2019.” MMWR. 17 May 2019.

“Measles Information.” Rockland County. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

McDonald, Jessica and Catalina Jaramillo. “Viral Video Makes False and Unsupported Claims About Vaccines.” FactCheck.org. 22 Jan 2021.

“As COVID and Monkeypox cases increase, scientists start testing wastewater to detect viruses.” WSBTV.com. 26 Jul 2022.

“Fulton County begins monitoring wastewater for coronavirus and monkeypox.” Press release. Fulton County. 25 July 2022.

“Fact Check-Atlanta-area drinking water has not been found to contain monkeypox.” Reuters Fact Check. 12 Aug 2022.

Spencer, Saranac Hale. “COVID-19 Is Caused by a Virus, Not Snake Venom.” 18 Apr 2022.