At a Cabinet meeting on Aug. 26, President Donald Trump proposed seeking the death penalty for anyone convicted of murder in Washington, D.C., claiming the death penalty is “a very strong preventative.” But the research, which has been difficult to conduct, is inconclusive on whether capital punishment is a deterrent.

A committee formed by the National Research Council concluded that existing academic research was “not informative” for settling the issue. As a result, the committee specifically recommended against making the type of claim Trump stated in deliberations about death penalty policies.

“Anybody murders something in the capital, capital punishment,” Trump said. “Capital — capital punishment. If somebody kills somebody in the capital, Washington, D.C., we’re going to be seeking the death penalty. And that’s a very strong preventative. And everybody that’s heard it agrees with it. I don’t know if we’re ready for it in this country, but … we have no choice.”

“So, in D.C., in Washington — states are going to have to make their own decision — but if somebody kills somebody … it’s the death penalty, OK?”

Trump’s remarks came two weeks after he announced a federal takeover of law enforcement in the city and the deployment of National Guard and federal law enforcement.

The district abolished the death penalty in 1981.

In 2012, a committee of scholars convened by the National Research Council — an arm of the the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine — surveyed the scientific literature on the effect of the death penalty on homicide rates and concluded that the research to that point was “not informative about whether capital punishment decreases, increases, or has no effect on homicide rates.”

The NRC committee “recommends that these studies not be used to inform deliberations requiring judgments about the effect of the death penalty on homicide. Consequently, claims that research demonstrates that capital punishment decreases or increases the homicide rate by a specified amount or has no effect on the homicide rate should not influence policy judgments about capital punishment.”

One of the members of that NRC committee, Philip Cook, professor emeritus of public policy and economics at Duke University, told us there has been no definitive research since that 2012 analysis on whether the possibility and application of capital punishment has an effect on the murder rate.

“It is intrinsically difficult to determine the answer from our experience,” Cook told us via email. “Homicide rates vary widely for all kinds of reasons. The statistical problem is to determine whether any part of that variation is due to capital punishment (or the lack thereof). The problem is especially difficult because the effect statisticians are trying to estimate is almost certainly small — only a very small fraction of homicides have any chance of resulting in the death penalty, and a still smaller fraction in actual execution.”

Another of the NRC committee members, Steven Durlauf, a professor at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, agreed, telling us via email, “There is no reason to update the conclusions of the NRC report” because “no new research has been produced that would change the conclusion.”

A review of research, Durlauf said, found that even minor changes in “statistical specifications” could produce very different results, showing a deterrent or no deterrent — and even “negative deterrent effects,” which would mean capital punishment actually raises homicides because it lowers the value attached to life.

Durlauf also cited the rarity of executions, and the long time it typically takes to carry out executions, as one of the biggest hurdles to research on the deterrent value of capital punishment.

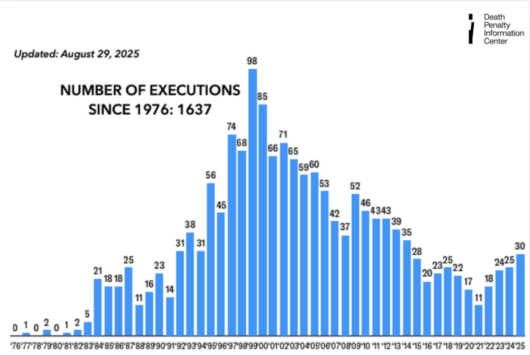

“Only about 20% of death sentences since 1976 have led to executions,” Durlauf said. “And executions are typically delayed for many years. Capital sentences are themselves rare compared to murders. The highest number of executions since 1976 is 98 in 1999, when there were 15,500 murders. These numbers indicate why discerning a capital punishment effect is so hard. Executions are a drop in the bucket compared to murders,” making it hard to discern “how fluctuations in their levels would deter” crime.

The Trump administration might argue that things would be different if death sentences were always given and always expeditiously implemented. But “there is no statistical evidence for this,” Durlauf said, and it’s different from what exists today.

“And, in my opinion, it is illusory to think quick, frequent executions can be implemented,” Durlauf said. “The system has many appeals, etc. built in out of fear of executing the innocent. (Whether it is foolproof is a different issue.) And there are reasons to believe juries will be more reluctant to give death sentences without safeguards.”

Robin M. Maher, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, concurred.

“There is no evidence that use of the death penalty acts as a meaningful deterrent against future violent crime,” Maher told us via email. “Studies completed over the past three decades have both failed to establish any deterrent effect and debunked other efforts suggesting there is a deterrent effect.”

Death Penalty in the U.S.

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit that studies capital punishment, there have been 1,637 executions in the U.S. since 1976, but there has been a steady decline in recent years. Only 108 executions have been carried out in the last five years. (There were more than three times that number in the five years between 1999 and 2003.) Currently, 27 states allow the death penalty, but many of those states have not executed anyone in years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

California, for example, has the highest number of inmates on death row — 585 — but it has not executed a prisoner since 2006. Although the death penalty remains on the books, Gov. Gavin Newsom placed a moratorium on the death penalty in the state in 2019, saying that it was “unfair, unjust, wasteful, protracted and does not make our state safer.”

Texas by far has had the highest number of executions — 595 since 1976. The next highest is Oklahoma with 128.

Capital punishment is still available as an option for some federal crimes, though there were no federal executions between 2003 and 2019. In Trump’s first term, the Justice Department restarted federal executions in July 2019, and between then and the end of Trump’s first term, 13 federal inmates were executed, the last less than a week before Trump left office.

In July 2021, under President Joe Biden, then Attorney General Merrick Garland imposed a moratorium on federal executions. A month before leaving office, Biden commuted the death sentence of 37 of the 40 people on federal death row to life sentences without the possibility of parole. The three exceptions were Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev; Dylann Roof, who was convicted and sentenced to death for murdering nine people at a historically Black church in Charleston, South Carolina; and Robert Bowers, who murdered 11 worshippers at a synagogue in Pittsburgh.

A White House fact sheet said Biden “believes that America must stop the use of the death penalty at the federal level, except in cases of terrorism and hate-motivated mass murder.”

Calling capital punishment “the ultimate deterrent,” Trump on his first day in office of his second term restored the pursuit of capital punishment “for all crimes of a severity demanding its use.” His executive order noted that federal prosecutors would seek federal jurisdiction and seek the death penalty for all cases involving the murder of a law enforcement officer or a capital crime committed by “an alien illegally present in this country.” In a separate executive order, Trump also encouraged federal law enforcement to detain those arrested in the district in federal custody and to pursue federal charges “whenever possible.”

We reached out to the White House press office for evidence that capital punishment for murder acts as a “preventative,” and asked how the president intends to enact his capital punishment policy in Washington, D.C.

“On Day One, President Trump signed an EO [executive order], restoring the death penalty and protecting public safety to strengthen federal and state options to use the death penalty for the most heinous crimes,” White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson told us via email. “Criminals should know that the Trump Administration will bring the full weight of the federal law, including the death penalty, against anyone who commits violent criminal acts. And victims and their families deserve justice across the country.”

But Cook, from Duke University, said the president may have difficulty enacting his plan.

“The federal criminal code limits the imposition of capital punishment to first degree murder with aggravating circumstances,” Cook said. “And certain defendants can’t be tried capitally,” such as those under age 18. So unless the administration ignores the federal code, he said, “only a fraction of defendants can possibly receive the death penalty in DC.”

There are practical concerns as well, he said.

“Capital prosecutions are subject to special procedural rules that make them enormously costly,” Cook said. “If DC really tried to apply the death penalty to every technically eligible defendant, it would swamp the current capacity of the court. One possible effect – not enough resources to try carjackers and nonfatal shooters and so forth.”

In Washington, D.C., the death penalty was abolished in 1981 by the D.C. Council. In 1992, the city’s residents voted overwhelmingly via a referendum against the death penalty. Five years later, the D.C. Council’s Judiciary Committee voted against a bill to allow the death penalty for those convicted of murdering a public safety employee.

Maher, of the Death Penalty Information Center, said she was “not aware of any presidential authority to unilaterally require the use of capital punishment in Washington DC.”

“There is currently no legal mechanism under which someone could be sentenced to death under DC law,” Maher said. “Federal law permits the federal government to seek a federal death sentence in all U.S. states and jurisdictions (including Washington DC) only if the crime is a federally death-eligible crime as defined by Congress.”

“If the President is suggesting imposing a change to DC law to require use of the death penalty, that would be an unprecedented use of federal authority that is likely to meet strong local and legal resistance,” Maher said. “If the President is suggesting that the death penalty should be an automatic, mandatory punishment for all murders committed in DC, he is suggesting something that has been unconstitutional for almost 50 years.”

Maher cited Woodson v. North Carolina, a case in which the Supreme Court in 1976 ruled 5-4 against mandatory death sentences saying, “The respect for human dignity underlying the Eighth Amendment … requires consideration of aspects of the character of the individual offender and the circumstances of the particular offense as a constitutionally indispensable part of the process of imposing the ultimate punishment of death.”

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.