President Donald Trump has said that Americans are now paying or will pay “the lowest price anywhere in the world for drugs,” thanks to the administration’s negotiations with pharmaceutical companies. The administration has announced discounted cash prices for a small number of brand-name drugs. There isn’t evidence Trump’s deals so far have led to broad decreases in drug prices, nor is it certain they will in the future.

Despite these caveats and ambiguities, Trump often has presented lower drug prices as a fait accompli. “We now are paying the lowest price anywhere in the world for drugs,” he said in a Jan. 27 speech in Iowa. “Every other president tried for it. They didn’t try very hard. They didn’t get anything. I got it done.”

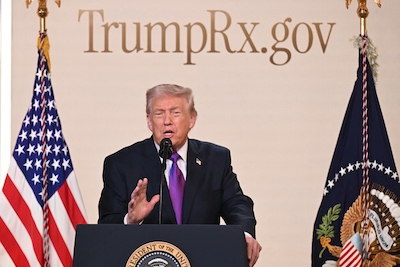

“The American people were effectively subsidizing the cost of drugs for the entire world, and it’s not going to happen any longer,” he said during the Feb. 5 launch for TrumpRx, the new federal website pointing people toward cash prices negotiated by the administration for brand-name drugs. “We ended it.”

The TrumpRx website makes similarly sweeping statements, claiming that the approach of basing U.S. prices off of prices in other countries — referred to as most favored nation, or MFN, pricing — is “guaranteeing huge savings for Americans.”

Trump’s efforts may have lowered prices for some consumers buying certain drugs. But experts told us there’s no guarantee of substantial savings for Americans in general.

Thus far, the Trump administration’s drug price negotiations have resulted in voluntary agreements with 16 companies, though many of the details remain unclear. Under those agreements, drug manufacturers have promised to offer discounts on select drugs to people who pay cash and are not using insurance. Companies have also agreed to launch new drugs or to offer Medicaid drugs at MFN prices. In exchange, the companies have said, they have been promised exemptions from tariffs and other benefits, such as exemptions from future mandatory MFN pricing.

“With rare exception,” the negotiations with drugmakers “don’t appear to have translated into actual savings for people at the pharmacy counter or for public or commercial payers yet,” Rena Conti, a health economist at Boston University Questrom School of Business, told us. These exceptions include certain weight loss and fertility drugs, which are often not covered by insurance to begin with and are now being offered at reduced cash prices, she said.

There is no single, easily tracked measure of drug prices in the U.S., making it challenging to assess broad claims about whether drug prices are rising or falling. Companies provide list prices, but individuals, health insurers and the government rarely pay these prices, often benefiting from rebates or other discounts.

That said, there are no signs of widespread slashing of list prices in the U.S. “Typically in January, we will see price increases for already-launched brand drugs, and just like we’ve seen in previous years, we saw prices rise,” Conti said. The median list price increase for hundreds of brand-name drugs so far in 2026 was 4%, which is the same median increase as in 2025, according to the research firm 46brookyln.

When we asked whether Trump is claiming that Americans in general are now paying the lowest prices, a White House spokesperson asserted they would in the future. “We are going to be paying the same if not lower than other wealthy nations,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “Either via TrumpRx or once the MFN deals are codified upon passage of Great Healthcare Plan.”

The Great Healthcare Plan is a series of health policy proposals, released Jan. 15, which Trump has called on Congress to pass as legislation. To lower drug prices, the plan calls for “codifying” MFN deals. The Trump administration has also said it will add more drugs to TrumpRx, and in December the administration released proposals to apply MFN pricing to a subset of Medicare beneficiaries.

It is unclear how or whether the MFN deals will be codified, however. Nor is it a given that even a widely applied MFN policy would reduce prices substantially.

Trump’s claim that he is the first president to lower drug prices also ignores past efforts that have had some success.

Separate from the MFN pricing efforts, the Trump administration has continued to negotiate lower Medicare prices for some specific drugs under the Inflation Reduction Act. However, this law was passed in 2022 under the Biden administration.

And rather than promoting these Medicare negotiations, the Trump administration is “talking about this unclear political pressuring that the White House is applying in general in the health industry and specifically on drugs,” Joseph Antos, a senior fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute, told us. AEI is a conservative-leaning think tank. “Is there any way to actually objectively measure the impact of any of that? I don’t think there is.”

Below, we explain what we know and don’t know about the impacts of Trump’s MFN negotiations and proposed policies on drug prices.

TrumpRx Features Some Savings Amid Misleading Messages

There is some support for Trump’s claim that he has lowered drug costs, in the case of a few specific drugs being offered at relatively low cash prices.

However, TrumpRx, the website the administration built to promote these cash prices, echoes Trump’s exaggerated claims about the scope of the price reductions.

TrumpRx shows cash prices for 43 drugs from five manufacturers that made deals with the administration. People can either print a coupon to use at pharmacies or, in some cases, go to a manufacturer’s website to make the purchase.

GoodRx, a prescription drug coupon site that launched in 2011, has partnered with the administration to provide many of the TrumpRx-branded coupons, and people can in some cases use GoodRx to access coupons providing the same Trump administration-negotiated prices.

The TrumpRx website advertises the “lowest cash prices” and shows discounts of 50% to 93% off the list price. But most people, particularly those with insurance coverage, don’t pay the list price.

“Manufacturers have agreed to discount prices on some drugs that are not well covered by insurance or already have generic competition, and that’s not nothing, but it’s not necessarily going to help a lot of people, right now anyway,” Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at KFF, told us. KFF is a nonpartisan health policy organization. She explained that most people with health insurance will fare better using their insurance than paying in cash.

For example, a person with health insurance who pays a flat copay for medications is unlikely to get a better price by going to TrumpRx, two economists from the University of Washington explained in an opinion piece published in STAT. In fact, the TrumpRx website says: “If you have insurance, check your co-pay first—it may be even lower.”

People with insurance also benefit from caps on their spending in the form of deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums, the economists wrote, as well as prices for drugs negotiated by their insurers. But for now, drugs purchased via TrumpRx are not counted toward deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums. “A family might hit their out-of-pocket maximum by midyear using insurance, after which their insurer pays 100% of the prescription cost for the rest of the year,” the economists wrote. “Under TrumpRx, the family would pay full freight all year long, with no ceiling on their out-of-pocket spending.”

One group of people who are sometimes asked to pay list prices for drugs are those without insurance or whose insurance does not cover a specific drug, Cubanski explained.

But even for those without insurance or whose insurance doesn’t cover a certain drug, Conti said, there are better deals available on the U.S. market for some drugs featured on TrumpRx. “The majority of drugs that are listed on the TrumpRx website actually have generic competition, and for consumers it pays to shop,” she said. “You can get a better deal by simply buying the generic, even when this coupon is being offered.”

GoodRx or Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs, another website that negotiates with drug manufacturers, offer cheaper cash prices for generic versions of at least 18 of the 43 brand-name drugs promoted on TrumpRx, according to a review by STAT. TrumpRx does not notify people that generics may be cheaper than the brand-name drugs.

Conti did highlight some drugs for which cash prices appear to be “good deals.” These include insulin, the fertility drug Gonal-F and the GLP-1 weight loss drug Zepbound. Patients may benefit from low-cost insulin, which is offered at $25 per 10 milliliters, if they have gaps in their insurance coverage or have a health plan requiring high out-of-pocket payments, she said. Fertility and GLP-1 drugs for weight loss cost more but are often not covered by insurance even for those who have it, so patients may benefit from buying them for reduced cash prices.

Gonal-F is now available on TrumpRx at $168 for the lowest strength, compared with its list price of around $966. There were already discounts available for people paying for the drugs without insurance, but “the price that’s listed on the TrumpRx coupon is lower than the price being offered by the specialty pharmacy, even with other special discounts available,” Conti said.

Zepbound is being offered for $299 per month for the lowest dose, reduced from a list price of $1,087. (However, the lowest dose of the drug had previously been available for $349 per month for cash buyers.)

Cubanski said the latest weight loss medication discounts “can be seen as a pretty direct byproduct of negotiations between the manufacturers and the White House,” but said that the makers of these drugs have been “steadily offering increasing discounts” even before the negotiations. This is partly because for a while, there were shortages of the drugs, she explained, and companies have been allowed to market relatively inexpensive compounded versions, even though the drugs are under patent and do not have generics.

“The competitive pressures in the GLP-1 market have likely been responsible to some degree for bringing down cash pay prices,” Pragya Kakani, a health economist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College, told us. She added that it is “challenging to disentangle the effects from the Trump administration’s MFN initiatives vs. pre-existing competitive pressures.”

Claims Touting Lowest International Prices Are Difficult to Verify

As for the claim on the website that TrumpRx is offering the “world’s lowest prices,” or the lowest in the developed world, this is challenging to check.

The Trump administration has provided limited information on how the prices were arrived at during the closed-door negotiations with drug companies. We asked the White House for more detail on what international prices the TrumpRx prices are being compared with, and a spokesperson told us the administration was using prices from other G7 nations but did not provide more details.

Cubanski said it is difficult to check whether prices are the lowest, as “there’s not a lot of transparency in drug pricing internationally.” It’s possible to find prices, but it’s unclear what rebates or discounts countries have negotiated off of these prices.

Conti agreed, adding that in many cases, brand-name drugs may not even be offered in other countries because other countries drop brand-name drugs once a generic is available. Since many of the drugs now promoted on TrumpRx are available as generics, it is challenging to determine international prices.

People can make statements about offering the lowest drug prices internationally “because it’s impossible to check,” Conti said.

Medicaid Deals With Unclear Impact

The Trump administration has also said that as part of the MFN deals, companies agreed to sell drugs at MFN prices to Medicaid programs. A voluntary initiative invites companies to negotiate prices for certain drugs “aligned with those paid in select other countries,” according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. The initiative launched in January, a spokesperson for the agency told us.

It remains unclear exactly what drugs are being offered to Medicaid at these prices and what companies and states are participating, Cubanski said. The CMS spokesperson told us that the agency hasn’t yet published a list with these details.

It’s also not clear MFN prices would compare favorably to the prices the programs are already getting. “States pay among the lowest prices through the Medicaid program for prescription drugs of all payers in the U.S.,” Cubanski said. “So whether the so-called most favored nation price that pharmaceutical companies will be offering on specific medications is lower than what states are currently paying isn’t really something that we’re able to rigorously quantify.”

The average net Medicaid prices for top-selling drugs are 65% lower than those in Medicare Part D, according to an analysis from the Congressional Budget Office, Kakani said.

Furthermore, Cubanski said, “People on Medicaid pay very little if not nothing for prescriptions, so the savings would be to the state and federal government, not to people with Medicaid directly.”

Conti said that the larger current issue for drug affordability for people on Medicaid is that provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will lead to health care coverage losses. The CBO estimated that the law would increase the number of uninsured people in the U.S. by 10 million over 10 years, with 7.5 million of those due to changes to Medicaid. “The administration is weakening insurance protections at the same time that they are offering out the hope of these potential deals,” she said.

No Evidence of Impact on Private Insurance

Despite the discounts for a limited group of cash payers, experts said that the Trump administration’s MFN deals do not so far directly affect drug affordability for those with private insurance.

“The biggest affordability challenges are ones that are related to very high-cost brand drugs,” Conti said. “It’s not obvious that much of what the administration is pursuing right now is going to really make a difference for people who are commercially insured and who are using these high-cost brand drugs.”

Kakani said that the MFN deals have only addressed commercial insurance in a limited way, to the degree that the negotiations might indirectly influence negotiations between drugmakers and insurers. However, she added that the TrumpRx prices “are unlikely to be lower than net prices commercial plans were already negotiating,” as many of the drugs “face significant competition.”

Recently, CMS Administrator Dr. Mehmet Oz has argued that the cash discounts the Trump administration has negotiated will translate into wider price reductions, including for people with private insurance, due to increased transparency.

“Now that everyone knows the true worldwide most favored nation drug prices, it’s going to allow employers, insurers and everyone in between to be able to take out the middlemen and drive those prices down,” Oz said in a Feb. 6 CNN interview. He suggested on CNN two days later that if employers saw a drug price on TrumpRx that was lower than what they were paying, they would ask for that price.

However, Conti disagreed that transparency would uniformly lead to better deals for Americans. She explained that the current opaque system likely allows some Americans to get particularly good deals on drug prices, because plans and pharmacy benefit managers are negotiating and passing on some savings as lower out-of-pocket costs and premiums.

“If we move towards more radical transparency in this system, yes, there are consumers that will benefit, absolutely,” she continued. “But it also might erode the company’s willingness to offer really good deals” to some payers.

Uncertainty About Broader MFN Policies

Trump has often said that drug prices will dramatically fall due to MFN policies, referring to discounts of as much as 80% or 90%.

As we have said, proposed MFN strategies range from voluntary deals to launch new drugs or offer Medicaid drugs at lower prices to mandatory MFN pricing for some Medicare beneficiaries or a “codified” MFN strategy.

However, experts said that many details are missing regarding these strategies. Drugs are often launched in the U.S. before they are available in other countries, Conti said. It’s unclear how the U.S. will ensure it is getting the lowest prices internationally if there are no prices in other countries yet.

In the case of Medicare, CMS has proposed mandatory pilot programs testing MFN prices for some beneficiaries. But it’s unclear what drugs and companies will participate. Drug companies that voluntarily agreed to Medicaid MFN pricing may be exempted, Cubanski said, which “could potentially undercut savings.” CMS has estimated that its two initiatives — impacting drugs given by physicians or prescription drugs picked up at pharmacies — will generate around $12 billion of savings to Medicare over seven years and $14 billion over six years. “That’s not nothing, but given that Medicare spends roughly $200 billion per year approximately on drugs,” Cubanski said, the programs don’t “really move the needle all that much.”

As for broader, mandatory MFN pricing, it could face political headwinds, Cubanski said. “Historically, Republicans have not been in support of efforts to regulate drug prices,” she said, and pharmaceutical companies would also be expected to push back.

Even if widely implemented, MFN pricing may or may not lead to widespread and substantial reductions in drug prices.

A survey of health policy experts published Feb. 4 in Health Affairs found that around half thought MFN pricing would “substantially reduce” average net prescription drug prices in the U.S. for branded drugs, even if such a policy were broadly implemented.

“The overall takeaway was it’s really hard to predict what the effect of this policy is going to be, and the simplistic idea that this is going to suddenly reduce drug prices by … 80%, 90% are probably just that – overly simplistic,” said Kakani, the study’s lead author.

Companies would likely change their international strategies in response to a broad MFN policy, Kakani said. Companies could make it more difficult for the U.S. government to determine what other countries were paying, by issuing rebates in other countries and not disclosing them; they could delay product launches abroad, particularly in countries with very low prices, to set a higher benchmark; or they could increase international prices to a degree that the U.S. did not pay significantly less than before.

Kakani added that drug prices in the U.S. are not as high as Trump’s 80% or 90% discount claims have implied, when compared with other countries. A RAND report, based on 2022 data, found that on average, U.S. prices are 2.78 times higher than in other developed countries, and 4.22 times higher when looking at brand-name drugs before adjusting for discounts by manufacturers, as we’ve written in the past. Generic drugs had lower prices overall in the U.S. than in most countries.

Antos pointed to practical challenges to setting MFN prices. For example, he said it is unclear how the proposed Medicare programs to try out MFN pricing are supposed to work. “CMS doesn’t have the authority to force Germany to tell them everything about their pricing, and they also don’t have the ability to get Pfizer to open its books,” he said.

“Trying to tie it to some kind of European price is doing it the hard way,” Antos said, suggesting that if the U.S. wants price controls, it could just ask more broadly for the already-good prices it gets for Medicaid. “We have domestic reference pricing right here.”

While Trump claimed that it would be other countries that now pay higher prices, Antos said that “by and large” manufacturers “are not in a position to renegotiate a price” with other countries. (As part of tariff negotiations, the U.K. did agree to increase what it pays for new drugs, although it’s unclear what will happen with drug prices in other countries overall.)

Antos said that regardless, any attempt at price setting is “not going to necessarily translate into lower prices at the drug store for most people.”

And it will be difficult to evaluate whether U.S. policies are making a difference for consumers. If copays or deductibles went down, for example, perhaps insurance companies would make up for this by slightly increasing the growth rate of premiums, Antos said, which would be hard to quantify because premiums go up each year and are driven by hospital and doctor costs.

“In other words, it’s very hard to know what the net impact of any of these policies is,” he said.

Update, Feb. 18: We added that Conti is at the Boston University Questrom School of Business.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.