When asked what he was going to do about the “gun problem,” President Donald Trump responded that “we have done much more than most administrations.” Trump has taken some action to strengthen federal gun control, but his administration also has eased gun restrictions.

Trump made his remark on Aug. 4, after the mass shootings in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, saying: “We’re talking to a lot of people, and a lot of things are in the works, and a lot of good things. And we have done much more than most administrations. And it does — it’s not — really not talked about very much, but we’ve done, actually, a lot. But perhaps more has to be done.”

Here’s what the administration has done, and not done, so far.

Fix NICS Act

On March 23, 2018, Trump signed into law an appropriations act that included the Fix NICS Act, a bipartisan measure aimed at improving the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. The act, pushed by Republican Sen. John Cornyn and Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy, and co-sponsored by a bipartisan mix of 76 other senators, required federal agencies to submit semiannual certification reports to the attorney general on their compliance with record-keeping and transmission requirements, and to come up with plans to increase coordination and automated reporting. It carried financial penalties for political appointees who didn’t comply.

The new law also required the attorney general to “establish implementation plans for each state and tribal government” and to “determine if the state is in compliance with the benchmarks contained in the implementation plan,” according to a February bipartisan letter from senators urging agencies, specifically the Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security, to fully comply with the act.

Universal Background Checks

Over the course of his presidency, Trump has sent mixed public signals about his support for universal background checks, which would cover private sales by unlicensed individuals, including some sales at gun shows and over the internet. But when the Democratic-controlled House passed such a bill in February, Trump said he would veto it, and the bill stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate.

In the wake of the deadly mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, Trump held a bipartisan meeting with members of Congress on Feb. 28, 2018, to discuss measures to address gun violence. During the meeting, Trump seemed to offer support for legislation — proposed by Sens. Joe Manchin and Pat Toomey after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012 — that would have expanded background checks to private sales by unlicensed individuals at gun shows and over the internet. The measure failed in a close 54-46 procedural vote in the Senate.

Here’s an exchange Trump had with Murphy, a supporter of the amendment:

Murphy, Feb. 28, 2018: Ninety-seven percent of Americans want universal background checks. In states that have universal background checks, there are 35 percent less gun murders than in states that don’t have them. And yet, we can’t get it done. There’s nothing else like that, where it works, people want it, and we can’t do it.

Trump: But you have a different president now … You went through a lot of presidents and you didn’t get it done. You have a different president. And I think, maybe, you have a different attitude, too. I think people want to get it done.

Murphy: Well, listen, in the end, Mr. President, the reason that nothing has gotten done here is because the gun lobby has had a veto power over any legislation that comes before Congress. I wish that wasn’t the case, but that is. And if all we end up doing is the stuff that the gun industry supports, then this just isn’t worth it. We are not going to make a difference. And so I’m glad that you’ve sat down with the [National Rifle Association], but we will get 60 votes on a bill that looks like the Manchin-Toomey compromise on background checks, Mr. President, if you support it. If you come to Congress, if you come to Republicans and say, “We are going to do a Manchin-Toomey-like bill to get comprehensive background checks,” it will pass. But if this meeting ends up with just, sort of, vague notions of future compromise, then nothing will happen.

Trump: I agree. We don’t want that.

Murphy: And so I think we have a unique opportunity to get comprehensive background checks, and make sure that nobody buys a gun in this country that’s a criminal that’s seriously mentally ill, that’s on the terrorist watch list. But, Mr. President, it’s going to have to be you that brings the Republicans to the table on this because, right now, the gun lobby would stop it in its tracks.

Trump: I like that responsibility, Chris. I really do. I think it’s time. It’s time that a president stepped up, and we haven’t had them. And I’m talking Democrat and Republican presidents — they have not stepped up.

Two days later, however, after Trump met privately with officials from the NRA, the White House “softened its tone” — as the Washington Post put it — on background checks. Asked about the president’s position on background checks, White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders told reporters, “Not necessarily universal background checks but certainly improving the background check system. He wants to see what that legislation, the final piece of it looks like. ‘Universal’ means something different to a lot of people.”

Instead, Trump signed the appropriations act that included the Fix NICS Act, as mentioned earlier.

After Democrats took control of the House in 2019, the House, on Feb. 27, passed the Bipartisan Background Checks Act — which, like the Manchin-Toomey legislation, would expand federal background checks to gun purchases and transfers between private parties, including some sold at gun shows or over the internet not covered by current law. The bill passed 240-190 largely along party lines, though eight Republicans voted for it.

The following day, the House passed the Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019, a bill that sought to close the so-called “Charleston Loophole” by extending the window for completing a background check from three to 10 business days.

In a policy statement, the administration signaled that Trump would veto both bills if they ever passed. The statement said the Bipartisan Background Checks Act “would impose burdensome requirements on certain firearm transactions.” According to the statement, the bill “would require that certain transfers, loans, gifts, and sales of firearms be processed by a federally licensed importer, manufacturer, or dealer of firearms” and “would therefore impose permanent record-keeping requirements and limitless fees on these everyday transactions.”

The bill “contains very narrow exemptions from these requirements, and these exemptions would not sufficiently protect the Second Amendment right of individuals to keep and bear arms,” the statement read.

As for the Enhanced Background Checks Act, the statement said Trump would oppose it because “[b]y overly extending the minimum time that a licensed entity is required to wait for background check results, [the bill] would unduly impose burdensome delays on individuals seeking to purchase a firearm.”

Neither bill has been taken up in the Senate, which is controlled by a Republican majority.

After the mass shootings in Texas and Ohio this past week, though, Trump again appears to be at least considering some version of a universal background checks bill.

Toomey and Manchin met separately with the president on Aug. 5 and later issued a statement saying, “This morning, we both separately discussed with President Trump our support for passing our bipartisan legislation to strengthen background checks to keep guns out of the hands of criminals, the dangerously mentally ill, and terrorists while respecting the Second Amendment rights of law-abiding gun owners and all Americans. The president showed a willingness to work with us on the issue of strengthening background checks.”

Before Trump traveled to Ohio and Texas on Aug. 7, a reporter cited the House-passed background checks bills that he threatened to veto and asked what he would support.

“Well, I’m looking to do background checks,” Trump said. “I think background checks are important. I don’t want to put guns into the hands of mentally unstable people or people with rage or hate, sick people. I don’t want to — I’m all in favor of it.”

Trump added that he saw “no political appetite” in Congress for a ban on assault rifles. But, he said, “There’s a great appetite — and I mean a very strong appetite — for background checks. And I think we can bring up background checks like we’ve never had before. I think both Republican and Democrat are getting close to a bill on — they’re doing something on background checks.”

Bump Stocks Ban

The Department of Justice and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives issued a new federal regulation on Dec. 18, 2018, officially banning bump stocks, or devices that can be attached to the rear of a semiautomatic rifle to make it shoot almost as fast as a fully automatic weapon. The ATF had previously ruled 10 times between 2008 and 2017 that certain models could not be prohibited under existing gun laws.

The devices became part of the national gun debate in October 2017 after 64-year-old Stephen Paddock used AR-style rifles affixed with bump stocks to shoot people attending an outdoor concert in Las Vegas. More than 50 people were killed and hundreds more were injured.

Then, in February 2018, after the Parkland, Florida, school shooting, Trump announced that he had signed a memorandum directing the attorney general to “dedicate all available resources to complete the review of the comments received, and, as expeditiously as possible, to propose for notice and comment a rule banning all devices that turn legal weapons into machineguns.” The following month, on March 23, the Justice Department announced that it was proposing a rule to that effect, which was finalized about nine months later — despite objections from the NRA.

The final rule required the owners of any bump stocks to destroy the devices or turn them in at an ATF office prior to March 26, when the rule went into effect.

Prosecuting Firearm Offenses

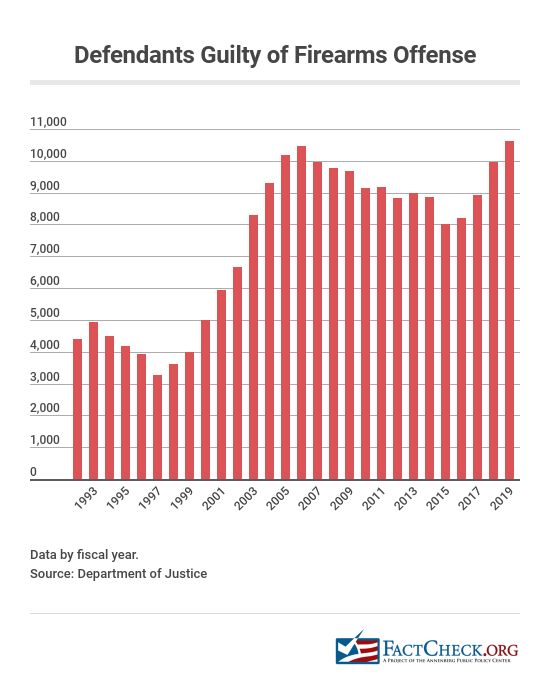

In his Aug. 5 remarks on the mass shootings in Ohio and Texas, Trump pointed to his administration’s record of prosecuting people who have violated federal gun laws. “Last year, we prosecuted a record number of firearms offenses,” he said.

There has been a notable increase in the successful prosecution of firearms offenses each year under Trump.

In fiscal year 2019, the Department of Justice successfully prosecuted 10,623 defendants of firearms offenses, according to data provided by department spokesman Peter Carr. That’s the most since at least fiscal year 1992, based on a review of the department’s annual statistical reports since fiscal year 1992. The previous high was 10,466 in fiscal 2006, as the chart below shows. (See “defendants guilty of firearms offense” in Table 3B in the fiscal 2010 report for fiscal years 1992 to 2010, and Table 3C in the fiscal 2017 report for fiscal years 2000 to 2017.)

Rescinded Social Security Rule

In late February 2017, Trump signed into law a joint resolution that eliminated an Obama-era rule requiring the Social Security Administration to report to the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System certain disability beneficiaries deemed unable to manage their finances due to a mental health condition.

The SSA rule, which was issued in December 2016, was created to comply with the reporting requirements mandated by the NICS Improvement Amendment Act of 2007, which was signed into law in January 2008 by President George W. Bush. The law required federal agencies to report individuals prohibited from acquiring guns to the NICS, and federal law prohibits someone “who has been adjudicated as a mental defective or has been committed to any mental institution” from buying or possessing a gun.

The SSA rule said that in order to be reported to the background check system, individuals had to meet five criteria, including having a severe mental disability and having a representative assigned to handle their benefit payments. The Obama administration estimated that the reporting requirement would cover “approximately 75,000 people each year who have a documented mental health issue, receive disability benefits, and are unable to manage those benefits because of their mental impairment, or who have been found by a state or federal court to be legally incompetent.”

Trump opposed the rule because it “could endanger the Second Amendment rights of law abiding citizens,” the White House said. The National Rifle Association, the American Civil Liberties Union and many disability rights groups also argued that it risked violating the rights of some beneficiaries by unduly preventing them from being able to buy firearms.

The legislation blocking the rule from being implemented passed 235-180 in the House, with only six Democratic votes, and 57-43 in the Senate, where four Democrats supported it.

Redefining ‘Fugitive from Justice’

In February 2017, under Trump, the Department of Justice narrowed the definition of “fugitive from justice” when determining who is prohibited from buying a gun. It issued a memo that said, “The current process of denying a NICS transaction based on the existence of an active warrant alone is no longer valid.” The Justice Department policy now applies the “fugitive from justice” prohibitor only to individuals who fled their state to “avoid prosecution for a crime or to avoid giving testimony in a criminal proceeding,” and who are “subject to a current or imminent criminal prosecution or testimonial obligation.”

The policy change settled a dispute between the ATF and the FBI that had lasted since at least 2008, according to a 2016 report by the Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General. The ATF had long maintained “that an individual is not a fugitive from justice if they remain in the state where the warrant was issued,” while the FBI had been denying “transactions involving the purchase of a firearm outside the county or other local jurisdiction where the warrant was issued, even if the purchase is within the same state.”

In November 2017, the Washington Post reported that, before Trump took office, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel “sided with ATF and narrowed the definition of fugitives” and said that gun purchases should only be denied to fugitives who crossed state lines.

“After Trump was inaugurated,” the Post said, “the Justice Department further narrowed the definition to those who have fled across state lines to avoid prosecution for a crime or to avoid giving testimony in a criminal proceeding.”

Funding Study of Gun Violence

Although academics have for decades said there is a critical need for more research into gun violence, the Trump administration has shown no interest in restoring government funding for such research.

Since the late 1990s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been wary of studying gun issues after the NRA objected to a series of studies that it claimed advocated for gun control. In 1996, NRA lobbyists convinced Congress to insert language, known as the Dickey amendment, in annual appropriations bills that says “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”

Compromise language accompanying a 2018 spending bill clarified that, while the prohibition remains, “the Secretary of Health and Human Services has stated the CDC has the authority to conduct research on the causes of gun violence.” But without funding allocated, the additional language didn’t mean much in practice, several researchers told NPR. In April, a CDC spokesperson told Politico, “Dedicated funding from Congress would help CDC to move forward in this work.”

This year, Democratic appropriators in the House allocated $50 million in next year’s budget to study gun violence: $25 million to the CDC and $25 million to the National Institutes of Health. It remains to be seen whether the Republican-controlled Senate will seek to strip that funding in negotiations this fall.

Trump has remained mum on the subject. In Trump’s bipartisan meeting with members of Congress in February 2018, Rep. Stephanie Murphy advocated removing the Dickey amendment from spending bills.

“It’s a key piece — having facts and scientific data is a key piece in helping us address this national public health issue,” Murphy said. “And so I would hope that we, as lawmakers, can have opinions about policies, but we should all have good sets of facts.”

Trump responded noncommittally, saying, “Okay. Thank you very much,” and then moved on to the next topic.

The president’s proposed budgets — which are largely a symbolic statement of priorities — have called for cutting the spending for the CDC and the NIH, and have not included money earmarked for research into firearm violence.

3D-Printed Guns

On June 29, 2018, the State Department settled a lawsuit that began during the Obama administration over the online publication of blueprints for 3D-printed guns. The State Department under the Obama administration blocked the online publication, arguing that the publisher, Defense Distributed, was violating firearm export laws and regulations, the Arms Export Control Act and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, since the data would be available to those abroad.

In a response to lawsuit brought by Defense Distributed against the State Department, the government also argued national security interests in the case, and both a district and appellate court sided with the State Department. The State Department under Trump initially continued the legal fight, but as our fact-checking colleagues at PolitiFact.com explained, the State Department made an abrupt settlement offer when the case turned to the issue of the defendant’s arguments about their First Amendment right to free speech.

The settlement allowed the company to proceed with the publication of 3D blueprints. That was promptly halted by an injunction from a district court judge after several state attorneys general filed suit against the State Department. That case, in the Western District of Washington, is still pending.

The Department of Justice opposed that injunction, arguing that the case was about the DOJ’s authority to control the export of items or services that “raise military or intelligence concerns.” The DOJ assured that if someone used the blueprints to actually manufacture plastic weapons, they would run afoul of federal law.

In a statement, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said, “Under federal law, it is illegal to manufacture or possess plastic firearms that are undetectable. Violation of this law is punishable by up to five years in prison. Such firearms present a significant risk to public safety, and the Department of Justice will use every available tool to vigorously enforce this prohibition.”

The Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence has filed suit as well against the State Department, seeking documents to explain why it had settled the case. After the State Department had won at every stage of the case, it “out of the blue folded its winning hand,” Joshua Scharff, an attorney at Brady, told us.

Trump himself wasn’t involved in the decision to settle, according to the White House. Trump tweeted on July 31, 2018, “I am looking into 3-D Plastic Guns being sold to the public. Already spoke to NRA, doesn’t seem to make much sense!” That was after the State Department’s settlement was made public. On Aug. 1, 2018, then-White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said the Justice Department “made a deal without the president’s approval.”

Suggested Arming School Staff

After the Parkland, Florida, school shooting in February 2018, Trump suggested arming teachers or school personnel to lessen or deter such attacks.

“It’s called concealed carry, where a teacher would have a concealed gun on them,” Trump said on Feb. 22, 2018, during a meeting with students, teachers and parents at the White House. “They’d go for special training. … So let’s say you had 20 percent of your teaching force, because that’s pretty much the number — and you said it — an attack has lasted, on average, about three minutes. It takes five to eight minutes for responders, for the police, to come in. So the attack is over. If you had a teacher with — who was adept at firearms, they could very well end the attack very quickly.”

Trump said, “We’re going to be looking at it very strongly,” and said he believed it could “very well solve your problem” because shooters “wouldn’t go into the school to start off with” if they knew school personnel were armed.

In December 2018, a Federal Commission on School Safety issued a report that discussed including armed school personnel in safety preparedness. It said states, districts and local schools should “[d]etermine, based on the unique circumstances of each school (such as anticipated law enforcement response times), whether or not it is appropriate for specialized staff and non-specialized staff to be armed for the sake of effectively and immediately responding to violence.”

The report outlined several questions schools and districts should ask in determining whether they should arm some personnel.

Reconsidering Gun Ban on Some Federal Lands

The Trump administration says it is reconsidering a Nixon-era policy that bans loaded guns on the almost 12 million acres of land and water managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, except where it allows hunting.

The policy was challenged in federal court, and the case now sits in federal appeals court. The Obama administration defended the ban in court, but in September of 2017, the New York Times reported, the Justice Department under Trump filed a motion stating that the Army Corps was “reconsidering the firearms policy challenged in this case.”

Although the ban currently stands, Corps spokesman Dough Garman told Politico this week, “The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is reconsidering the regulation that governs the possession and transportation of firearms and other weapons at Army Corps of Engineers water resources development projects.”

NYC Gun Rule

In May, Justice Department attorneys filed a brief asking the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn a federal court of appeals decision upholding a New York Police Department rule that, in most cases, banned certain gun-license holders from transporting their handguns from the home or business address on their handgun license.

“Few laws in the history of our nation, or even in contemporary times, have come close to such a sweeping prohibition on the transportation of arms,” the brief said. “And on some of the rare occasions in the 19th and 20th centuries when state and local governments have adopted such prohibitions, state courts have struck them down. That is enough to establish that the transport ban is unconstitutional.”

In January, the Supreme Court agreed to review the case — New York State Rifle and Pistol Association, Inc. v. City of New York — which was originally filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in 2013. In a motion filed in July, however, the city requested that the Supreme Court order the case to be dismissed because both the NYPD rule and state law have been amended and, the city argues, make the lawsuit “moot.”

“[T]he City has amended the challenged regulation to enable holders of premises licenses to transport their handguns to additional locations, including second homes or shooting ranges outside of city limits,” and “the State of New York has amended its handgun licensing statute to require localities to allow holders of premises licenses to engage in such transport,” the motion states. “Independently and together, the new statute and regulation give petitioners everything they have sought in this lawsuit. The Court should accordingly vacate the decision below and remand with instructions to dismiss — or at least to consider in the first instance whether any Article III case or controversy still exists.”

The case is still pending, though.