Economists cite several reasons for high inflation in the United States, starting with the unprecedented circumstances created by the COVID-19 pandemic. But TV ads in midterm races across the country blame one culprit: stimulus spending by President Joe Biden’s administration.

That spending — the American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021 — has been a factor “and not an unimportant one,” George Selgin, senior fellow and director emeritus of the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute, told us, echoing the view of other economists. But it “certainly has not been the whole story.”

Meanwhile, Democrats aren’t shy about picking favorites in the inflation blame game, either. Biden, as we’ve written before, focuses on the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, saying, “it’s not because of spending.”

Asked whether both sides were oversimplifying the issue, Alex Arnon, associate director of policy analysis for the Penn Wharton Budget Model, told us: “That’s an easy yes.” Arnon went on to say it was hard to disentangle all of the elements affecting inflation.

With the latest figures showing that inflation rose 8.6% year-over-year in May, and in the wake of several interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve to control inflation, the topic has, not surprisingly, become a theme of midterm ads attacking Democrats. In the month of June alone, 76 Republican TV ads mentioning inflation started airing, according to Kantar, which provides data on political advertising.

Republican Sen. Ron Johnson and the National Republican Senatorial Committee, for instance, launched a TV spot on June 22 that claims “$5,000 a year” is “the burden of Joe Biden’s inflation tax on Wisconsin families.” That figure is a Bloomberg Economics estimate, published in late March, for how much more a U.S. household, on average, would have to spend for the same basket of goods in 2022, compared with last year, due to inflation. But the estimate doesn’t break down the dollar amount by the inflationary factors causing the price hikes. It notes increased savings and higher wages would “cushion those costs.”

Johnson’s TV ad, though, only mentions “Biden’s massive deficit spending” for causing higher grocery and gas prices. The campaign pointed us to a Vox article from May that — as we do here — explored how much of a role the American Rescue Plan has played in inflation. It noted the United States’ problem was “more severe, to at least some extent” than inflation in other countries due to higher amounts of stimulus here. But that doesn’t mean Bloomberg’s $5,000 average cost estimate is pinned all on Biden, as the ad suggests.

Similarly, a string of ads from a group called One Nation says that a “liberal spending spree” is “jacking up inflation,” that “the highest inflation in 40 years” was “triggered by a massive surge in government spending” or that this spending “raised gas and grocery prices over 8%.” The ads are airing in support of Johnson in Wisconsin and against Democratic Sens. Raphael Warnock in Georgia and Catherine Cortez Masto in Nevada. And in Alabama, Republican Katie Britt, who won the Republican primary runoff in late June, and a group supporting her used the inflation issue in ads blaming “Biden’s liberal spending.”

Economists have said the American Rescue Plan — a $1.9 trillion pandemic relief measure that included $1,400 checks to most Americans; expanded unemployment benefits; money for schools, small businesses and states — has contributed to high inflation, though estimates vary on how much. Jason Furman, a former economic adviser to President Barack Obama and now a Harvard University professor, told us his estimate is 1 to 4 percentage points and when “pressed for one number,” he uses the midpoint of 2.5. Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s — whose work is often cited by the White House — said the impact of the stimulus measure now “has largely faded.”

The ARP came after two other pandemic stimulus laws were enacted under Trump, worth a total of $3.1 trillion. That spending, too, could have contributed to inflation. (Selgin said more spending, other things being equal, makes prices go up, as does a shortage of goods.) But the concern, particularly with the March 2020 relief law, was squarely on boosting the economy and aiding the millions of Americans who lost their jobs. The ARP came later, on top of trillions that already had been spent.

The relief spending, however, is hardly the only inflation factor, with the fallout from the pandemic the root of the matter. And while most economists we spoke with said the American Rescue Plan should have been smaller or the money spent more slowly, they said some level of stimulus was needed. They noted there were positive economic effects to the measure, too, helping insure a robust recovery.

We’ll go through the causes of inflation and what role the American Rescue Plan has played.

Causes of Inflation

The first factor, Arnon said, is that “obviously” the economy is coming out of “exceptional” circumstances. The shutdown of the economy during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, followed by the quick recovery was “unlike anything before.”

“It was pretty much inevitable … we were going to see some friction” that would mean higher prices, he told us.

Wendy Edelberg, director of The Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, who served on the president’s Council of Economic Advisers under Obama and George W. Bush, similarly said it all started with the pandemic. “I do think that in many ways [inflation] traces back to the pandemic because the pandemic has interacted with everything else that has happened to create the mess that we’re in,” she said. But “we wouldn’t be seeing what we’re seeing right now without other factors.”

Selgin said that earlier in the pandemic people were spending less, with fewer opportunities to spend. Plus, it was necessary for the government to take steps to allow people to have earnings. At the same time, productive activity was limited, which “makes goods more scarce,” he said. “Other things equal, that makes prices higher.”

And once spending picked back up “that lack of productivity would become more and more evident as a source of higher prices.” There were also consequences for the United States from the limit on world productivity, Selgin explained.

With supply shortages, increased savings in Americans’ bank accounts and a desire to avoid public activities due to COVID-19, people spent their money on goods. “We just gorged on goods,” is the way Edelberg put it, outfitting our home offices, acquiring home exercise equipment, buying more food to use at home and making other pandemic purchases.

In addition to savings from simply not going out and doing as many things, households received those government stimulus checks, three rounds of them. The CARES Act, enacted in late March 2020, gave up to $1,200 to Americans earning under $75,000 in adjusted gross income. At the end of 2020, Trump signed another COVID-19 relief measure that provided $600 to most Americans, well short of the $2,000 that both Trump and Biden wanted.

Two and a half months later, on March 11, 2021, Biden signed the American Rescue Plan, with $1,400 going to most Americans.

Edelberg said her reading of the data is that consumers “took that enormous fiscal support and while still not feeling comfortable with all of the face-to-face services, they focused their spending on goods,” a sector that “had already been pretty crippled by the extraordinary increase in goods spending throughout the pandemic.”

In some months, real — meaning inflation-adjusted — spending on goods was 15% above trend. “That’s crazy,” she said. “Even in the best of circumstances, our goods sector would not be able to keep up with that level of demand for that long.”

But it wasn’t the best of circumstances. There were also labor issues, with workers out sick or not interested in working in some jobs, and supply issues with imports coming from other countries.

Edelberg said she does expect some decline in the prices of goods, because demand is now dropping. Consumers are starting to buy more services, however, and there’s “very strong inflation in the services sector.”

The chart below tweeted by Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, shows personal consumption expenditures, for goods and services, above the trend line.

Nothing to see here, folks. Demand is totally normal and inflation is on a supply issue. https://t.co/xZoaM0JkB9 pic.twitter.com/n02ssf71hm

— Marc Goldwein (@MarcGoldwein) June 13, 2022

In 2022, these pandemic-related factors were “compounded very seriously by the Ukraine war and the sanctions that have been applied to Russia,” Selgin said.

Furman told New York Magazine in May that “[n]o one expected 8.5 percent inflation. I don’t think that would have been a reasonable thing to have thought. One point or more of our inflation, really, is Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.”

The “biggest story” over the past few months, Arnon told us, is energy prices, which dominate how the public thinks about inflation. It’s “really hard to overestimate the impact in gas prices in how people experience inflation,” he said.

He said there’s “not an especially strong” link between the ARP and energy prices. The ARP contributed to demand, which affects demand for energy overall, but Arnon said such an impact would be “small.”

As we’ve written before, experts have said higher gas prices aren’t the fault of the Biden administration, but rather the result of pandemic-related supply-demand repercussions that have been exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Oil supply dropped early in the pandemic, and then struggled to keep up with surging demand. After Russia invaded Ukraine, several countries put sanctions on Russian oil and the U.S. banned imports completely.

According to the International Energy Agency, Russia is the largest exporter of oil to the global market, with most of those exports going to Europe. So the fallout from the conflict has affected global supply.

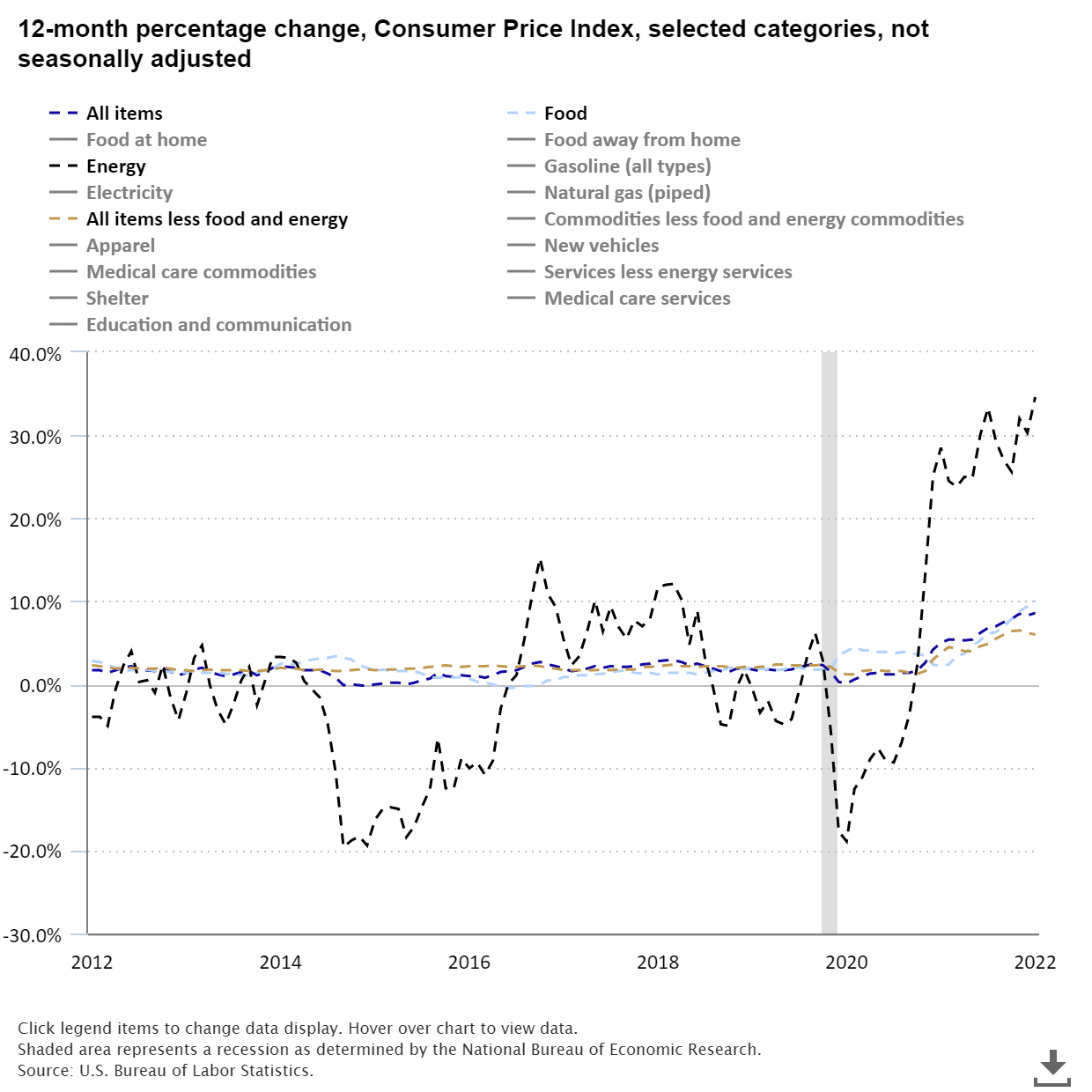

The May figures on the Consumer Price Index showed energy prices up 34.6% over the prior 12 months and gas prices up 48.7%. By comparison, food prices had increased 10.1%, and all prices minus food and energy (what’s called “core inflation”) had gone up 6%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (Go to the BLS page to explore the data further.)

The Biden administration has emphasized that inflation is a global issue. It is. Countries around the world are experiencing the same types of pandemic- and Russia/Ukraine-related influences. But there are differences by country, and the difference in the U.S. is largely higher amounts of stimulus, economists say.

So far this year, energy and commodity prices have been “much worse in western Europe for households,” Arnon said. In the U.S., “we brought the economy back up faster and we are dealing with some of the costs of doing that in terms of higher inflation.”

Moody’s Analytics, in a February 2022 report, said the “well over $5 trillion” in fiscal support in the U.S. under both Trump and Biden equaled nearly 25% of gross domestic product, compared with less than 18% in the United Kingdom and about 10% for all countries on average.

Selgin cited a “noticeable gap” between inflation, including core inflation, in the U.S. and Europe.

The latest figures from Eurostat show inflation overall at 8.1% in May for the Euro area, and core inflation — without energy and unprocessed food — at 4.4%. In the U.S., the May figures are 8.6% overall and 6% for core inflation.

A March paper by economists with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found a similar gap throughout 2021 in comparing the U.S. to a sample of nine countries. Pre-pandemic, the economists said the U.S. core inflation was on average 1 percentage point above the sample. “By early 2021, however, U.S. inflation increasingly diverged from the other countries,” they wrote. “U.S. core CPI grew from below 2% to above 4% and stayed elevated throughout 2021. In contrast, our OECD sample average increased at a more gradual rate from around 1% to 2.5% by the end of 2021.”

While the estimates of the impact of the ARP on inflation vary, “most economists agree that it’s a big part of the explanation for that difference,” Selgin said.

The Impact of the American Rescue Plan

There are no hard estimates of how much the American Rescue Plan contributed to the higher inflation the U.S. is experiencing. Asked if there were any good studies on this, Arnon said there was nothing he would call “especially reliable.”

The White House has pointed to work by Moody’s Analytics to bolster its claim that there hasn’t been much of an impact from the ARP. Moody’s February report said the stimulus measure temporarily contributed to inflation, “almost entirely in the first half of 2021,” and that without the law, unemployment would have been higher, crediting the ARP for “adding well over 4 million more jobs in 2021.”

In a June 12 Twitter post, Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s, said the ARP contributed only 0.1 percentage points to year-over-year inflation in May and now the “Russian invasion and spike in oil and other commodity prices is the #1 reason, followed by the pandemic & the housing shortage.”

Zandi told us in an email that he does think the ARP “added significantly to inflation a year ago, but at the time that was considered a feature and not a bug, as inflation had been uncomfortably low and well below the Federal Reserve’s target for more than a decade. But I don’t think the ARP is adding meaningfully to inflation currently.” He said the impact “has largely faded.”

Others disagree. As we said, Furman said his estimate was about 2.5 percentage points, with a range from 1 to 4 percentage points.

Selgin told us a “good guess might be 2 to 3” percentage points.

The San Francisco Federal Reserve report echoes that 3 percentage points estimate, but it comes with caveats. The March 28 report said that figure may have been the impact from fiscal support by the fourth quarter of 2021, but noted the estimate comes with “considerable uncertainty because the available sample is too short for any greater precision.” Plus, it said there may have been worse economic outcomes without the spending.

“However, without these spending measures, the economy might have tipped into outright deflation and slower economic growth, the consequences of which would have been harder to manage,” the authors wrote.

Edelberg, too, said the law had positive economic effects. “When people say the American Rescue Plan has been to blame for inflation,” she said, “what’s their counterfactual?” If they say it shouldn’t have been quite as big — “well, absolutely.” But if the counterfactual is that nothing should’ve been done, that would mean we would be in a weaker economy. Inflation would be lower, “but I don’t like that world.”

Furman has said it wasn’t the size of the ARP but how quickly it was spent that was the problem. “It would have been fine to spend $2 trillion dollars,” he told New York Magazine in November, “but to spread that money out over time. By concentrating so much of it so quickly, it added kerosene to what was already a fire.”

Furman said in January 2021, before the ARP was passed, that the spending “should be contingent on the pace of recovery,” and other economists, such as Larry Summers, who was treasury secretary under President Bill Clinton and a top economic adviser to Obama, warned of inflationary impacts from the legislation before it was passed. But some of the blame on the law is hindsight.

When the American Rescue Plan was passed, Edelberg thought it would “make the economy run hot and create inflationary pressure.” That was “mostly widely understood,” she told us. But “by no means I expected the extraordinary inflation we’ve seen.” She said she didn’t expect the makeup of consumer spending, with spending heavily on goods, to be “so crazy” and she expected people to return to work faster.

She was wrong on both factors, and both are because of the pandemic. “In retrospect,” she said, “we could’ve done a much better job of calibrating the size of the American Rescue Plan.”

What the legislation did was “give us a huge amount of insurance that we were going to have a robust recovery,” she said.

Edelberg and Arnon told us policymakers likely saw the ARP as a tradeoff: a stronger recovery at the risk of some inflation.

“It was far from clear that this would be more inflationary than was desired,” Arnon said, explaining that it was a choice between risking a recovery with higher unemployment and businesses not able to reopen with the risk of “reopening the economy way too fast and throwing off some of this friction that was going to lead to inflation.” Policymakers “chose between those two risks I think pretty deliberately.”

Now, with the ability of hindsight, he said, most economists agree the ARP was too big.

The legislation was “clearly a factor” in inflation, especially at the end of 2021 and early this year, Arnon said, but now the impact “has pretty clearly been swamped by the rise in energy prices.” He said there’s “not an especially strong” link between the ARP and energy prices.

The ARP helped cushion the blow for consumers from those higher gas prices, and other higher prices, even as it contributed to inflation overall.

More Blame to Go Around

Selgin told us it was clear that total spending from all sources — not only the fiscal stimulus — was responsible for “more than half of the inflation and probably three quarters of the inflation we see.” That includes bank lending, which increased as the COVID-19 pandemic waned and has contributed to private spending.

“That’s the component the Fed is tamping down on,” he said.

Speaking of the Federal Reserve, it gets a piece of the blame, too, Selgin said, and it has the responsibility to control inflation, with interest rates.

In the runup to the passage of the ARP, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell said inflation wasn’t a major concern. In early March 2021, he said as the economy reopens there could be “some upward pressure on prices” but he didn’t expect it would last long.

The Fed didn’t raise the benchmark interest rate until a year later, by 0.25 percentage points in March. It then raised the rate again by 0.5 percentage points in May. On May 12, Powell said in an interview with the radio show Marketplace that with “perfect hindsight … it probably would have been better for us to have raised rates a little sooner. I’m not sure how much difference it would have made, but we have to make decisions in real time, based on what we know then, and we did the best we could.”

On June 15, the Fed raised rates by another 0.75 points.

Edelberg agreed the Fed “made mistakes here, too.” She thinks they hoped, as she also did, that the composition of spending would go away quickly and people would return to work faster. “Had monetary policy been a lot more aggressive after the American Rescue Plan was passed … we’d see more modest inflation now for sure.”

There is plenty of responsibility to go around, Arnon said, citing an “unusually rough few years for commodity markets,” climate events and conflicts that have affected production in some countries, and an underinvestment in supply-chain infrastructure. There has been “a lot of mess lately.”

Campaign ads and political talking points rarely capture this level of nuance. The Republican ads have a point — the American Rescue Plan did contribute to higher inflation, many economists say — but the Biden administration has a point, too — the global pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also provoked price hikes. Yet, the political messaging doesn’t tell the whole story.

Furman told New York Magazine in May that “it’s not all fair” for voters to blame Democrats, mentioning that global oil markets and the independent actions of the Fed are other factors. “But, you know, if you’re the incumbent, rightly or wrongly, you sort of own everything.”

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.