Both political parties are spinning the facts on whether the Democrats’ Inflation Reduction Act would raise taxes.

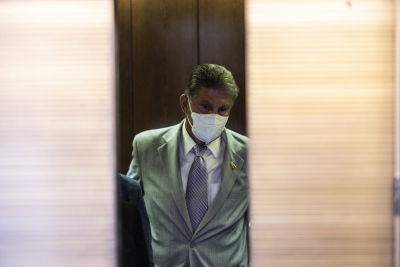

Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin says the climate bill “does not raise taxes” but merely closes tax “loopholes.” Republicans say it does raise taxes and would break President Joe Biden’s pledge not to raise taxes on people making less than $400,000 a year.

Republicans say that since higher corporate taxes lead to reductions in stock values and workers’ wages — both of which fall, in part, on earners throughout the income scale — Biden has broken his pledge. But in promising during the campaign not to raise taxes on those making below $400,000, Biden always followed that up with promises that he would make corporations “pay their fair share.”

The Inflation Reduction Act would invest about $385 billion in energy and climate change incentives including tax credits for the production of solar and wind energy equipment and the purchase of electric vehicles, and another roughly $100 billion in health care expenditures, mainly for an extension of subsides for health insurance policies purchased via the Affordable Care Act exchanges. (For an explanation of the climate-focused provisions in the bill, see our story “How Does the Inflation Reduction Act Address Climate Change?”)

The bill also seeks to create about $320 billion worth of health care savings, in part by lowering Medicare drug costs by allowing Medicare to directly negotiate drug prices and limiting out-of-pocket prescription drug costs to $2,000 per year.

The biggest revenue-producer in the plan is a corporate minimum tax of 15% on companies that report profits in excess of $1 billion, a measure that is expected to bring in about $315 billion over 10 years. The plan also includes funding for increased IRS enforcement and seeks to end the “carried interest” tax benefit that allows managers of investment funds to pay a lower capital gains tax rate, rather than income tax rates.

(Update, Aug. 5: To secure the support of Democratic Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, Democratic leaders scrapped the provision to eliminate the carried interest tax benefit.)

In all, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projects the savings and revenue would come to $790 billion, paying for all of the spending in the bill plus reducing the annual deficit by a total of about $305 billion over 10 years. The Penn Wharton Budget Model projects the bill would reduce cumulative deficits by $248 billion over 10 years.

The Senate Democrats plan to pass the bill using the reconciliation process, which would require only 51 votes in the Senate. The reconciliation bill is a scaled-down version of Biden’s Build Back Better bill, which stalled after Manchin announced in December that he would not support it. But in what came as a surprise to many on the Hill, Manchin on July 27 announced his support for the Inflation Reduction Act. It has not yet come up for a vote in the Senate.

Update, Aug. 18: Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law on Aug. 16.

The Rhetoric from Both Sides

On “Fox News Sunday” on July 31, Manchin was asked about his past comments expressing concern about raising taxes and the fact that some experts say the Inflation Reduction Act technically does raise taxes. Manchin replied, “They’re wrong, it does not raise taxes.” He added that what it does is “close loopholes.”

“We’re not putting a burden on any taxpayers whatsoever,” Manchin said on CNN’s “State of the Union.”

Republicans disagree.

“Joe Biden and Democrats want to raise taxes during a recession,” Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel said in a statement on July 28.

According to the RNC, “The Biden tax hikes break his promise to not raise taxes on Americans making less than $400,000.”

In a speech on the bill on July 28, Biden said the bill was about “making the largest corporations in America pay their fair share,” and he insisted, “This bill will not raise taxes on anyone making less than $400,000 a year … a promise I made during the campaign and one … that I have kept.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer echoed those sentiments in remarks from the Senate floor the same day.

“Republicans go on and on and on about how this is a tax on the American people: No, Republicans. You try to hide the truth,” Schumer said. “The truth is this bill will close tax loopholes exploited by the wealthiest Americans and largest corporations and will not touch Americans who make below $400,000 a year.”

Does It Raise Taxes?

Let’s start with the claims from Manchin and Schumer that the bill would not raise taxes and that it simply closes tax loopholes.

The bill would impose a corporate minimum tax of 15% on companies that report profits in excess of $1 billion. Although the current statutory corporate tax rate is 21%, Senate Democrats say some 200 or more large corporations pay below 15% due to various tax incentives. That minimum tax is expected to raise about $315 billion over 10 years.

Whether that is a tax increase or merely “closing a tax loophole,” may be a matter of semantics, but two experts we interviewed said this was a tax increase. Corporations subject to that tax will pay more in income taxes to the federal government than they otherwise would without the bill.

“It is a tax increase,” Will McBride, vice president of federal tax and economic policy at the Tax Foundation, told us in a phone interview. “That’s the way the office of the nonpartisan scorekeepers, the Joint Committee on Taxation, sees it. They call it a tax increase, and we call it a tax increase.”

The definition of a loophole is somewhat “in the eye of the beholder,” and often amounts to a political term for a tax provision you don’t like, Steven Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, told us in a phone interview.

Rosenthal said he views a tax loophole as a company finding a way to avoid taxes in a way that Congress did not intend. But by and large, corporations are paying below the statutory corporate tax rate because they are taking advantage of various tax incentives, like bonus depreciation, which Congress enacted to encourage investments and stimulate the economy.

“Many provisions of the code are there by design,” Rosenthal said. “Congress expects companies to avail themselves of these provisions. I’d be hard pressed to label those as loopholes.”

And so, Rosenthal said, contrary to what Manchin and Schumer claim about the bill, “Yes, it raises taxes. It’s more than just closing loopholes.”

Biden’s Tax Pledge

But Rosenthal also disagrees with Republican claims that the bill would break Biden’s pledge not to raise taxes on people making less than $400,000. “I think that’s also wrong,” he told us.

When Biden was campaigning in 2020 on the pledge, he also vowed repeatedly to make corporations “pay their fair share.”

“Everyone knew what Biden meant when he made this pledge during the campaign,” Rosenthal said.

Republicans point to a Joint Committee on Taxation analysis of the bill, which indicates federal taxes for people making less than $200,000 would rise by $16.6 billion in 2023, and that those taxpayers would be shouldering just over 42% of the tax increases in the bill that year. That’s a function of estimating the effect on individuals of collecting the minimum corporate tax. Corporations pass along some of the burden of higher taxes in the form of lower wages and lower stock values, affecting shareholders.

In 2013, the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation began including the distributional effects of business taxes on individuals.

“The new methods adopted by the Joint Committee staff for distributing taxes on corporations and taxes with respect to income of passthrough entities reflect the current understanding in the economics profession that domestic individuals ultimately bear the majority of the burden of these taxes,” the JCT wrote. “Given the general economic consensus that these taxes should be distributed to individuals, the Joint Committee staff believes that estimating the distribution is appropriate.”

In other words, as then-presidential candidate Mitt Romney once famously said, “Corporations are people, my friend.” Or, as McBride put it to us, “Some human pays this tax.”

For its modeling JCT assumes that over the long term, 75% of corporate taxes fall on capital owners of those corporations, meaning that tax increases reduce stock values, for example, and shareholders take some of the hit. The JCT also assumes workers shoulder about 25% of the burden of corporate taxes over the long term, mainly in the form of lower wages or other compensation.

Given that even middle- and low-income workers own stocks through IRAs and 401(k)s, McBride said, the burden of corporate tax hikes are felt “all over the income scale.” In addition, longer term, workers also bear some burden of corporate tax hikes via lower wages, he said.

Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, told us that while there is a small increase for middle-income people in the first year, by the third year of the bill, JCT’s modeling shows the percentage increases are almost negligible.

In addition, Goldwein said, JCT’s distributional tables do not include the benefits of individual energy tax credits, savings from the prescription drug provisions, health care subsidies and a reduction of inflation over time. If they did, he said, the net impact of the bill would be closer to zero for middle-income Americans in the early years, and over time would result in a net tax benefit for middle-income earners.

So while there would be some individuals worse off economically if the bill passes, Goldwein said, “every income class overall is benefiting from the bill.”

The JCT’s analysis of the overall impact of the bill shows it would raise about $68 billion over 10 years. But most of that comes from the early years. In fact, by 2027, the bill would amount to a net tax cut for individuals each year, according to the JCT.

As for the bill’s elimination of the “carried interest” tax benefit that allows managers of investment funds to pay a tax rate lower than income taxes, the $15 billion in revenue it is projected to raise is a relatively small part of the overall package. And the bill specifically restricts carried interest to those making over $400,000.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.