Summary

The U.S. faces the possibility of another recession — the third in 11 years — if President Obama and Congress cannot find a way to avoid the so-called fiscal cliff. The one-two combination of massive tax increases and spending cuts scheduled to take effect, beginning Jan. 1, would push the unemployment rate back above 9 percent, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

There’s a growing consensus in Washington that some combination of spending cuts and increased revenues is needed to reduce annual deficits and slow the federal debt — without going over the fiscal cliff. The disagreement is over the details, particularly over how and how much to increase tax revenues and where to cut spending.

Some Republicans, including House Speaker John Boehner, say the president’s tax proposals would “destroy nearly 700,000 jobs,” which is an exaggeration. Many Democrats would prefer not to cut entitlement programs as part of the negotiations, even though the three largest entitlement programs — Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security — would consume 55 percent of all federal spending by 2022, compared with 43 percent in 2011, according to the CBO.

We take no position on what Congress should do. But we can offer some factual context to help understand the scope of what the CBO calls the nation’s “fundamental budgetary challenges.”

Some facts to consider:

- The scheduled tax increases, if allowed to take effect, would net an additional $536 billion in fiscal year 2013, according to the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, raising more than $5 trillion in 10 years. Nearly 90 percent of Americans would pay more in taxes, TPC says, with the average increase being nearly $3,500.

- The automatic spending cuts scheduled to take effect would cut $1.2 trillion over 10 years, split roughly in half between domestic and military spending.

- Obama’s plan calls for increasing revenue by $1.6 trillion over 10 years. Republican congressional leaders have not proposed a counter offer for revenues, but during the so-called “grand bargain” negotiations in the summer of 2011, Boehner reportedly had agreed to $800 billion worth of increased revenue.

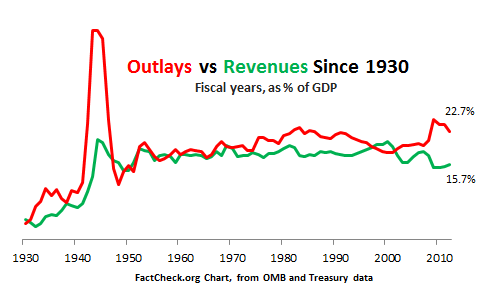

- As a percentage of the nation’s economy, the federal government now spends 22.7 percent and collects in revenue 15.7 percent — a large gap that has persisted for years and has contributed to four straight years of $1 trillion deficits.

- A bipartisan fiscal commission created by Obama has proposed capping revenues at 21 percent by the year 2022, and getting spending below 22 percent.

The Analysis below provides details on these and other facts.

Analysis

The fiscal cliff was created by a series of actions by Congress, beginning with the approval of the Bush-era tax cuts in 2001 and 2003.

The Bush tax cuts were extended by the Tax Relief Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization and Job Creation Act of 2010. But the 2010 tax legislation did more than that. It also extended some of the tax breaks in President Obama’s 2009 stimulus bill and temporarily reduced the Social Security payroll taxes.

A year later, Congress passed the Budget Control Act of 2011, which Obama signed into law. That law imposed spending caps on discretionary spending through 2021 that are supposed to save $917 billion over 10 years, according to an August 2011 analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

The law also created a special bipartisan congressional committee charged with reducing the deficit by at least $1.5 trillion over 10 years. But the so-called super committee failed to agree on a deficit-reduction plan and, under the Budget Control Act, $1.2 trillion in automatic budget cuts over 10 years are now scheduled to take effect, beginning in January. At the same time, the temporary tax cuts approved under both Bush and Obama are due to expire.

Tax Increases Looming

In an Oct. 1 report on the fiscal cliff, the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center estimates that the scheduled tax increases, if allowed to take effect, would net an additional $536 billion in fiscal 2013. How significant is that? Federal revenues were about $2.45 trillion in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30 — meaning the scheduled tax increases alone would raise revenues by about 22 percent.

In its report, TPC lists six reasons why taxes are scheduled to increase by so much:

- The Bush-era tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 and extended for two years at the end of 2010 are set to expire. Cost: $254 billion.

- Temporary tax breaks that were part of Obama’s stimulus law and extended at the end of 2010 will expire. Cost: $27 billion.

- Congress has yet to act on short-term tax breaks, mostly for businesses, that are routinely extended but have yet to be approved. Cost: $75 billion.

- A temporary payroll tax cut enacted for 2011 was extended through 2012, but is now set to expire at the end of this year. Cost: $115 billion.

- Tax increases contained in the Affordable Care Act on upper-income taxpayers will go into effect: a 3.8 percent tax on unearned income, 0.9 percent increase in Medicare payroll taxes and a higher income threshold for deducting medical expenses. Cost: $24 billion.

- The Alternative Minimum Tax, which was designed to make sure wealthy Americans pay a minimum tax, was never indexed to inflation on a permanent basis. As a result, Congress must fix this problem — as it has every year since 2001 — or 28 million more taxpayers will pay higher taxes. Cost: $40 billion.

If all that happened, taxes would increase an average of $3,466 per household, according to the TPC. Middle-income households — those earning nearly $40,000 to about $64,500 a year — would see an average increase of $1,984.

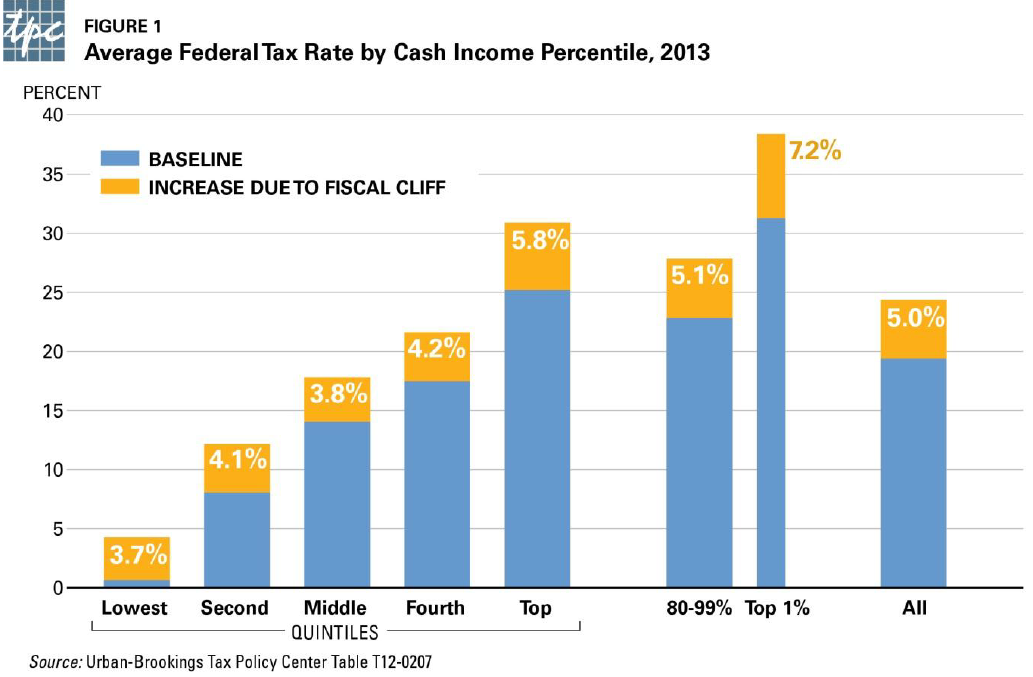

The chart below from the Tax Policy Center shows the impact on average tax rates for taxpayers in different income groups (as defined in a footnote on the last page of the report):

Congressional leaders say they are confident that they will negotiate a deal that will avoid some if not most of these tax increases from taking effect.

Congressional leaders say they are confident that they will negotiate a deal that will avoid some if not most of these tax increases from taking effect.

What is likely to happen?

Congress is widely expected to “patch” the AMT. In its report on the fiscal cliff, the TPC ranked the AMT tax the least likely to increase among nine categories of pending tax increases. In urging Congress to pass an AMT “patch,” the IRS said 28 million taxpayers, “many of them middle-class families,” would pay more in taxes if Congress fails to act.

On the other hand, the tax increases contained in the Affordable Care Act are expected to take effect next year now that Obama has won reelection. Those taxes would fall most heavily on upper-income taxpayers. TPC says taxpayers earning more than $108,266 would see an average increase of $1,141 a year.

There is less certainty about the other scheduled tax increases — particularly the Bush-era tax cuts, which reduced tax liability on earned income, capital gains and dividends, and the estate tax.

Under current law, the marginal individual income tax rates would all snap back to pre-2001 levels. As the TPC explains, the 10 percent tax bracket will disappear, making the lowest bracket 15 percent, and the “25 percent, 28 percent, 33 percent, and 35 percent rates will revert to 28 percent, 31 percent, 36 percent, and 39.6 percent respectively.”

Allowing the Bush-era tax cuts to expire for individuals earning less than $200,000 and married couples earning less than $250,000 would cost those taxpayers $171 billion, or nearly a third of the total $536 billion “cliff,” according to the TPC.

If Congress does extend the Bush tax cuts for those taxpayers, as the president has proposed, then the total average tax increase for middle-income taxpayers would drop from $1,984 to $1,096, according to the Tax Policy Center. The AMT “patch” would reduce the potential tax hike for those same taxpayers another $104 a year on average — dropping the average tax increase for middle-income taxpayers to less than $1,000 by virtue of those two actions.

The Bush-era tax cuts for the upper-income taxpayers appear to be at a greater risk of expiring — unless the parties can negotiate an agreement to raise revenue elsewhere to keep the lower tax rates in place. TPC estimates that the income tax changes would raise $44 billion from individual taxpayers who earn $200,000 and couples earning $250,000.

In addition to the individual income tax changes, other major changes slated to take place that will affect the wealthy include these:

- The estate tax: The current $5.1 million per-person exclusion from the federal estate tax is scheduled to fall to $1 million, and the top tax rate is scheduled to rise to 55 percent in 2013. That would raise an estimated $31 billion in 2013.

- Capital gains and dividends: The tax rate is 15 percent on long-term capital gains (assets held at least one year) and qualified dividends for taxpayers in the top four tax brackets (currently ranging from 25 percent to 35 percent). The capital gains rate is scheduled to increase to 20 percent for those taxpayers, while dividends would return to being taxed at regular income tax rates. Estimated impact: $8 billion.

There’s uncertainty for low- and middle-income taxpayers, too.

As we mentioned earlier, the 2010 tax legislation cut the employee portion of the Social Security payroll tax. The rate fell from 6.2 percent to 4.2 percent in 2011 and 2012.

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner testified before the election that he did not support extending the payroll tax cut again. The New York Times quoted him as saying: “This has to be a temporary tax cut. I don’t see any reason to consider supporting its extension.” Now, however, the administration is negotiating to “include an extension of the payroll tax cut or an equivalent policy aimed at working-class families,” the Times reported on Nov. 29.

The expiration of the payroll tax cut would mean that middle-income taxpayers would see an average tax increase of $672 per year, according to the TPC.

In addition to the expiration of the payroll tax cut, there were a host of tax credits in the president’s 2009 stimulus legislation that were extended in 2010 and are now due to expire. Obama expanded the earned income tax credit, increased the value of the child tax credit for low-income families, and expanded and increased the college tuition credit.

The Tax Policy Center says the credits benefit about 152 million taxpayers, and more than half of them earn less than $50,000 a year. For example, a taxpayer earning $20,113 or less would pay an average of $209 more in taxes if the credits expire, the TPC analysis shows (Table 6). That’s about half of what that taxpayer’s total increased tax liability would be — $412 — if all of the fiscal cliff tax changes went into effect as scheduled.

Closing the Gap

There is a growing consensus in Washington that there needs to be a combination of increased revenues and spending cuts to close the big gap that has developed in recent years between revenues and outlays.

As a percentage of the nation’s economy, the gap between what Washington spends (22.7 percent) and collects in revenues (15.7 percent) narrowed slightly in the last fiscal year. But the federal government is still a long way from the times when revenues more closely matched spending — as you can see from the chart below. We created the chart using historical budget data from the federal Office of Management and Budget, updated with Treasury Department figures for the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2012.

Since fiscal year 1946, a post-World War II federal government has run surpluses in 12 of 68 years — most recently for a period of four straight years, beginning in 1998 under President Bill Clinton.

The government’s checkbook benefited in the Clinton years from the effects of a large tax increase pushed by the Democratic president in 1993, his first year in office. That tax increase fell most heavily on those making more than $200,000 — which is why the tax rates under Clinton are cited frequently (but not entirely accurately) by Obama in his push to allow the marginal individual tax rates to rise in the top two brackets. (We’ll get to Obama’s plan later.)

Clinton’s fiscal 1994 budget also contained limits on spending, particularly in the military following the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991. When the House passed that budget, the New York Times reported that there was roughly a 1-for-1 ratio between spending reductions and tax increases over a five-year period.

The surpluses evaporated as the nation went through two wars and two recessions — the first triggered by the dot-com bust, which began in mid-2000. Deficit spending returned in fiscal 2002 and worsened after the second recession. The federal government has now posted four straight years of $1 trillion deficits.

In March, the Congressional Budget Office projected that under the president’s proposed budget for 2013, spending would equal 23.4 percent of GDP while revenues would be 17.2 percent. The deficit, CBO said, would equal 6.1 percent of the economy that year and average 3.2 percent over the 10-year period ending in 2022. But the CBO currently projects that a continuation of current policies — including the Bush-era tax cuts and an AMT “patch” — would push the deficit to 6.5 percent of GDP in 2013, with spending and revenues equal to 22.8 percent and 16.3 percent, respectively.

In an op-ed piece, Warren Buffett, the chairman and chief executive of Berkshire Hathaway, wrote that the government should aim to raise revenues to 18.5 percent of GDP while keeping spending to around 21 percent. Acknowledging that this wouldn’t eliminate deficits, he wrote that “this ratio of revenue to spending will keep America’s debt stable in relation to the country’s economic output.”

The president’s bipartisan fiscal commission, on the other hand, called for more revenues in a report issued back in December 2010. As part of its “six-part plan to put our nation back on a path to fiscal health, promote economic growth, and protect the most vulnerable among us,” the commission proposed capping revenues at 21 percent by the year 2022, and getting spending below 22 percent and eventually to 21 percent by 2035.

And the CBO issued a report in November saying that there are many options for reducing our deficits. But continuing on the current path, CBO said, was not one of them.

The Opening Proposals

Both Democrats and Republicans have been talking about the need to compromise on the fiscal cliff. But what is their starting position in these negotiations?

Obama laid out his vision in his 2013 budget proposal. Overall, his plan calls for increasing revenues by $1.6 trillion over 10 years. (During the “grand bargain” negotiations between Obama and House Speaker Boehner in the summer of 2011, Boehner had agreed to $800 billion worth of increased revenue.)

There are a number of corporate tax implications in Obama’s plan, but here are the major parts affecting individual taxpayers:

- Allow the Bush tax cuts to expire for couples making over $250,000. Specifically, that would increase the top tax rate from 35 to 39.6 percent. That’s expected to generate $442 billion over 10 years. (page 219)

- Reduce the value of itemized deductions and other tax preferences to 28 percent for families with incomes over $250,000. That is expected to generate $584 billion over 10 years. (page 220)

- Increase capital gains tax rates from 15 percent to 20 percent, raising $36 billion over 10 years.

- Increase taxes on dividends from 15 percent to 39.6 percent. That’s expected to raise $206 billion over 10 years.

That’s the meat of Obama’s plan, but as he said in a news conference on Nov. 9, “I’m not wedded to every detail of my plan. I’m open to compromise. I’m open to new ideas.”

There has been no consensus plan yet proffered by Republicans, though last year the House passed a bill to extend the Bush tax cuts for everyone for another year.

More recently a number of Republican leaders have floated the idea of capping itemized deductions as a way to raise revenue without raising tax rates.

For example, on ABC’s “This Week” on Nov. 25, Sen. Lindsey Graham said:

Graham, Nov. 25: I’m willing to generate revenue. It’s fair to ask my party to put revenue on the table. We’re below historic averages. I will not raise tax rates to do it. I will cap deductions. If you cap deductions around the $30,000, $40,000 range, you can raise $1 trillion in revenue, and the people who lose their deductions are the upper-income Americans.

During the presidential campaign, GOP nominee Mitt Romney floated a proposal during the second debate to cap itemized deductions at $25,000.

Romney, Oct. 16: And so in terms of bringing down deductions, one way of doing that would be to say everybody gets — I’ll pick a number — $25,000 of deductions and credits. And you can decide which ones to use, your home mortgage interest deduction, charity, child tax credit and so forth.

The Tax Foundation analyzed a $25,000 cap and concluded it would raise about $1.3 trillion over 10 years.

So why do some Republicans prefer caps on itemized deductions to higher tax rates? Mark Duggan, professor of business economics and public policy at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, said a higher rate “hurts incentive to work.” Second, he said to us in an email, “when you exclude some things from the tax base you introduce distortions. By excluding health insurance, mortgage interest, etc. you subsidize certain goods (health care and housing) but not others. Furthermore the subsidies are bigger for those with high incomes where rates are highest.”

One option not being considered is doing nothing — thus allowing the spending cuts and the tax increases to take effect. What’s the consequence of that? CBO projects that the nation will most likely slide into a recession and the unemployment rate, which was 7.9 percent in October, would rise to 9.1 percent.

But short-term pain would be followed by long-term gain, the CBO says.

CBO, Nov. 8: CBO projects that the significant tax increases and spending cuts that are due to occur in January will probably cause the economy to fall back into a recession next year, but they will make the economy stronger later in the decade and beyond. In contrast, continuing current policies would lead to faster economic growth in the near term but a weaker economy in later years.

On the spending side of the equation, Obama’s position has not budged much from the position he outlined in September 2011 in his President’s Plan for Economic Growth and Deficit Reduction.

The president’s plan boasts of $4 trillion in “savings” from spending over 10 years. To get to that figure, the president included roughly $1 trillion in spending cuts that he had already signed into law in the Budget Control Act; savings from drawing down the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; and $580 billion in “cuts and reforms” to an array of mandatory programs — everything from agricultural subsidies to federal civilian worker retirement plans. Also included in that figure is $248 billion in reduced spending on Medicare and $73 billion on Medicaid.

The Spin

There are an awful lot of numbers and scenarios being thrown around by politicians regarding the fiscal cliff. We find that some are false and misleading, while others are accurate, but show an incomplete picture.

For example, Obama several times has stated that if the Bush tax cuts are not extended for families making under $250,000, “A typical middle-class family of four would see its taxes rise by $2,200.” The White House has even launched a campaign asking Americans to, “Tell us what $2,000 means to you and your family.” The White House is also encouraging people to “keep the conversation going online” on Facebook and Twitter using the hashtag #My2K.

The White House construction is accurate, but very specific. Note that in the online appeal, Obama is pictured at a table with two parents and their two children. According to a White House fact sheet, a married couple with two children with income between about $50,000 and $85,000 would see a tax increase of $1,000 because of a Child Tax Credit reduction; a tax increase of $890 due to the merging of the 10 percent tax bracket into the 15 percent tax bracket; and a tax increase of $310 because of the expiration of marriage penalty relief that provides a larger standard deduction for married couples. In total, that comes to $2,200.

As this breakdown makes clear, the biggest part of the tax increase comes from the fact that they are married and have two kids. The tax impact is much less for unmarried people without children, or even married people with one or no children.

According to calculations by the Tax Policy Center, those in the middle-income quintile, who earn roughly between $40,000 and $64,000 would see — on average — a $961 tax increase next year if the Bush tax cuts are not extended. (It comes to about $1,100 for those earning between $50,000 and $75,000 — which is closer to Obama’s parameters.)

The Tax Policy Center has created a tax calculator with which taxpayers can determine how much various fiscal cliff scenarios may affect them.

Other claims from politicians include:

- Raising taxes on upper-income earners would “destroy nearly 700,000 jobs in our country.” We looked at this when Boehner said it recently. It’s based on a report from the accounting firm Ernst & Young that assumed revenue from the taxes would be used “to finance a higher level of government spending,” even though Obama would use the added revenue to reduce the deficit.

- Among wealthy taxpayers who would be hit with an increase under Obama’s proposal, Boehner said, “more than half of them are small-business owners.” According to a 2011 report from the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis, more than 90 percent of small-business owners wouldn’t be affected by Obama’s proposal. But upper-income taxpayers do account for 57 percent of the income of small-business owners, which is what Boehner’s spokesman says he meant to say.

- “Social Security does not add one penny to our debt.” We fact-checked that claim when Democratic Sen. Richard Durbin said it on ABC’s “This Week” on Nov. 25. It’s false. The federal government for the first time in its history had to borrow money in 2010 to cover Social Security benefits to retired and disabled workers — a trend that worsened in 2011 and will not change at any point in the future unless changes are made.

— by Eugene Kiely, Robert Farley and D’Angelo Gore

Sources

Congressional Budget Office. “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022.” 22 Aug 2012.

“Background: Bush Tax Cuts.” Tax Policy Center. Undated, accessed 29 Nov 2012.

“2010 Tax Act.” Tax Policy Center. Undated, accessed 29 Nov 2012.

U.S. House. “H.R. 4853, Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010.” 5 Jan 2010.

Williams, Roberton et al. “Toppling off the Fiscal Cliff: Whose Taxes Rise and How Much?” Tax Policy Center. 1 Oct 2012.

Congressional Budget Office. “Monthly Budget Review.” 5 Oct 2012.

“Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010: Information Center.” IRS. 4 Aug 2012.

Press release. “Payroll Tax Cut Temporarily Extended into 2012.” IRS. 23 Dec 2011.

Taylor, Andrew. “Hill leaders voice confidence in debt deal.” Associated Press. 16 Nov 2012.

Rodibaugh, Jennifer J. “Experts Predict AMT Patch, Temporary Extension of Many Tax/Budget Provisions, No Payroll Tax Cut Extension.” CCH Group. 9 Nov 2012.

Paul Cherecwich Jr., chairman, IRS Oversight Board. Letter to Sen. Max Baucus. 19 Nov 2012.

Lowrey, Annie. “Payroll Tax Cut Is Unlikely to Survive Into Next Year.” New York Times. 30 Sep 2012.

Weisman, Jonathan. “G.O.P. Balks at the White House Plan on Fiscal Crisis.” New York Times. 29 Nov 2012.

“Questions and Answers for the Additional Medicare Tax.” IRS. 4 Aug 2012.

Press release. “In 2012, Many Tax Benefits Increase Due to Inflation Adjustments.” IRS. 20 Oct 2011.

Congressional Budget Office. “An Analysis of the President’s 2013 Budget.” Mar 2012.

Robillard, Kevin. “Report: Max Baucus wants to preserve estate-tax cut.” Politico. 26 Nov 2012.

Tax Policy Center. “Fiscal Cliff Analysis, Step 5 of 9: Stimulus Legislation EITC, CTC, AOTC.” 1 Oct 2012.

The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. “The Moment of Truth.” Dec 2010.

Office of Management and Budget. Historical Tables (Table 1.2—Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-) as Percentages of GDP: 1930–2017). Accessed 26 Nov 2012.

U.S. Department of Treasury. “Joint Statement of Secretary Geithner and OMB Deputy Director for Management Jeffrey Zients on Budget Results for Fiscal Year 2012.” 12 Oct 2012.

Jackson, Brooks. “Fiscal FactCheck.” FactCheck.org. 15 Jul 2011.

Office of Management and Budget. “Fiscal year 2013 Mid-Session Review: Budget of the U.S. Government. Table S-6 Proposed Budget by Category as a Percent of GDP.” 27 Jul 2012.

Congressional Budget Office. “An Analysis of the President’s 2013 Budget: Table 1. Comparison of Projected Revenues, Outlays, and Deficits under CBO’s March 2012 Baseline and in CBO’s Estimate of the President’s Budget.” Mar 2012.

Congressional Budget Office. “Choice for Deficit Reduction.” Nov 2012.