President Donald Trump has repeatedly said that Obamacare is “dead,” but recently he has been making a misleading boast about low insurance premium growth for 2019 marketplace plans.

Trump claimed that “the rates are far lower than they would have been under the previous administration,” adding, “because we’re managing it very, very carefully.” One study disputes that, and experts say most administration actions in the past two years have driven premiums up.

The actions the administration has taken “by and large have destabilized the market,” said Cynthia Cox, the director of the program for the study of health reform and private insurance at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Experts also espouse a longer view at the trajectory of premiums for the individual market, where people buy their own insurance, including on the Affordable Care Act exchanges, such as HealthCare.gov. The expected low average premium change for 2019 plans comes after a double-digit increase last year — which was also under the Trump administration and driven by the administration’s elimination of cost-sharing subsidies and uncertainty over the ACA’s future.

This year, there was less policy upheaval.

Many of the factors affecting premiums “have settled down this year,” Kelley Turek, the executive director of employer and commercial policy at the insurer trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans, told us. In addition, after several years under the ACA, “we are getting to a point where issuers are getting a better sense of this market,” she said, such as the population, their health costs and how to price plans.

The president made his claim on Sept. 17 at an event at the White House to launch the National Council for the American Worker. Trump spoke about new regulations for association health plans, to be created by groups of employers, and then said, “we have the remnants of Obamacare.”

Trump Sept. 17: “But the thing that I really am very happy to announce is that the rates are far lower than they would have been under the previous administration, or under a Democrat administration. We’re holding the rates down. So that remnant is being able to — the remnant of Obamacare is much less expensive than people thought. They were going up, before I got here, at 118 percent, in some cases; 150 percent, 160 percent, 55 percent. We have the percentage going up at a much lower level because we’re managing it very, very carefully. So we’re very proud of that.”

In August, in a Fox News interview, the president similarly said, “You know, we’ve mostly got it killed … but we’re getting the remnants of Obamacare — the increase is much less than people thought. That’s because of us.”

The average increase announced by the Department of Health and Human Services in October 2016 — before Trump became president — for the 2017 plan year was 25 percent for the second-lowest cost silver plan available on HealthCare.gov, which covered 38 states. Trump, as he did during the presidential campaign, cherry-picks particularly high increases in certain states or cities, though the highest we found was a 145 percent increase in Phoenix. The rate changes varied widely — Indianapolis saw a 12 percent decrease at the other end of the spectrum.

It’s worth noting there have been high increases in some states and cities under Trump as well: For the 2018 plan year, the average increase was 133 percent in Cedar Rapids, for instance. And the average increase for the second-lowest cost silver plan across HealthCare.gov states for a 27-year-old was 37 percent. Silver level plans in particular increased due to the elimination of cost-sharing subsidies, as we’ll explain.

After the president made his remarks, HHS Secretary Alex Azar announced on Sept. 27 that the “benchmark” silver plan, on which federal subsidies are based, is projected to decrease for HealthCare.gov states by 2 percent on average for 2019 plans. He gave credit for that to the president.

Final rates will be released sometime in October.

2019 Premiums

It’s true that the premium increases for 2019 plans are expected to be low.

An analysis published in early September by the Associated Press and the consulting firm Avalere Health of state rate filings by insurers found a 3.6 percent average increase for 47 states and Washington, D.C., for 2019. Avalere Health has since updated that figure to 2.8 percent for 48 states plus D.C. The analysis looked at overall premiums in rate filings for 34 states and final rates for 14 states.

The 2018 premium increase had been about 30 percent on average nationwide, the AP reported.

HHS reported a 37 percent average increase in the second-lowest cost silver plan for 2018, and, as Azar announced, is now projecting a 2 percent average decrease for HealthCare.gov states for 2019.

Why is there such a large drop in premium growth?

“This year, there was an absence of disruption,” in terms of policy changes, Dan Mendelson, the founder of Avalere Health, told us in a phone interview. “In other words, markets were stable.” And the second factor is an expectation of slower growth in medical expenses, a factor he doesn’t think “any politician can take credit for.”

Others say that low premium growth for 2019 might have been even lower yet were it not for some political disruption this year.

“Individual market premiums will be higher in 2019 than they would have been without the administrations’ policies,” Matthew Fiedler, a fellow with the Center for Health Policy in Brookings’ Economic Studies Program, told us in an interview.

Fiedler, who was the chief economist on the staff of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration, analyzed what premiums would have been in 2019 in a “stable policy environment,” which meant that the 2018 policies toward the individual market would remain in effect. This scenario, then, would keep the individual mandate penalty next year (which will be eliminated as part of the tax cut law) and wouldn’t include any new regulations on association health plans or short-term limited duration plans (as announced by the administration this year to expand these offerings that don’t have to meet all of the requirements of the ACA).

“I estimate that the nationwide average per member per month premium in the individual market would fall by 4.3 percent in 2019 in a stable policy environment,” Fiedler wrote in the report.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office expects healthier individuals to join those association and short-term plans, which would then increase premiums for those remaining in the individual and small-group markets. CBO said in a May report that it expects premiums in those markets to increase by an estimated 2 percent to 3 percent “in most years” due to these measures.

Mendelson, though, said it would be “a considerable amount of time” before markets form for those plans.

Average premiums also may be going up more slowly for 2019 because some insurers increased premiums substantially last year.

“There have been a lot of balls in the air in the policy realm and some uncertainty that really set into premiums last year,” Turek, with America’s Health Insurance Plans, said in an interview.

Among that uncertainty: a debate over repealing and replacing the ACA in Congress, concern that the individual mandate would end, and the administration’s elimination of cost-sharing subsidies, or cost-sharing reductions, that were paid to insurers to reduce out-of-pocket costs for low-income policyholders. The ACA caps the amount policyholders have to spend out of pocket on deductibles, copays and coinsurance, and the cost-sharing subsidy lowers that cap. The insurers were still required to offer the lower-cap policies even though the administration ended the subsidy payments in October 2017.

“Those are all factors that led to some larger premium increases for the 2018 year,” Turek said.

Cox, with the Kaiser Family Foundation, similarly told us that premiums are growing more slowly this year than in the past because insurers have been overpriced this year. “Going into 2018 insurers raised their rates significantly in large part because of this political uncertainty. In some cases, I think it’s likely insurers guessed too high,” she said.

In particular, insurers were encouraged in many states to increase premiums for silver-level plans, more so than bronze or gold plans, because of the loss of the cost-sharing subsidies, which applied only to silver-level plans.

The Kaiser Family Foundation’s tracking of insurer rate filings for 2019 plans has found about a 5 percent increase in the second-lowest cost silver plans for a 40-year-old in cities for which there is complete data, Cox said in an interview. As we’ve seen in other years, the rate changes vary across the country, from a 24 percent decrease in Philadelphia to a 23 percent increase in Burlington, Vermont.

Many insurers built in increases last year anticipating that the individual mandate would be eliminated. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ June brief on the drivers of 2019 premium increases acknowledges this as well, saying that the elimination of the mandate would drive premiums up next year to the extent that it “hasn’t already been incorporated into premiums.”

But AHIP, in a brief it published earlier this year, still estimated a 9 percent to 10 percent increase in premiums for 2019 due to the repeal of the mandate penalty.

Administration Actions

That AHIP brief also estimated increases due to medical costs, and the regulations on association and short-term plans. However, it estimated a 3 percent decrease in premiums due to a one-year moratorium in 2019 on a tax on health insurers.

Experts said that’s one move the administration has made that would drive premiums down.

States also have taken actions to depress premium growth. Some states have proposed, and the administration has approved, waivers to create reinsurance programs, which will reimburse insurers for high-dollar medical claims. Seven states have received such waivers, according to the journal Health Affairs.

Whether the states or the administration gets credit for those waivers is a matter of opinion. Azar gave credit to the president for the approval of the waivers in his remarks on Sept. 27.

Azar also cast the administration’s actions on cost-sharing subsidies as a positive, even though experts say ending the subsidies drove premiums up. He said, “We took bold action to fix a lawless situation in which the previous administration made payments to insurers that Congress never funded.” Azar said the president supported a bipartisan bill to “fix this situation,” which was a measure to reinstate the cost-sharing payments for at least two years. It failed.

The CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation have estimated, based on insurers’ rate filings, that premiums for silver-level plans are about 10 percent higher on average for 2018 due to the elimination of the cost-sharing payments, and the “agencies project that the amount will grow to roughly 20 percent by 2021.” Those receiving premium tax credits to buy insurance are also now receiving larger tax credits, since those are based on the silver plans.

Larry Levitt, senior vice president for health reform at the Kaiser Family Foundation, tweeted that there was a stabilizing effect from eliminating the cost-sharing payments. “Ironically, one of the most stabilizing actions the Trump administration has taken was cutting of cost-sharing subsidy payments to insurers. That led to an increase in ACA benchmark premiums this year, which in turn led to higher premium subsidies and more stable enrollment,” he said on Sept. 27.

Overall, Levitt said, “ACA premiums are stable for 2019 because they went up so much this year due to an uncertain environment and regulatory actions by the Trump administration. Premiums would be going down a lot if not for repeal of the individual mandate penalty and expansion of short-term plans.”

This year, the administration also ended, but then reinstated, payments to insurers for a risk-adjustment program that compensates insurers that cover more high-risk consumers. The program had been challenged in court, and the administration issued a new rule giving further justification for the financial formula the program uses. If the program had ended entirely, premiums would have gone up.

The HHS secretary also cited an executive order that Trump signed his first day in office, which called for HHS and other agencies to “delay the implementation of any provision or requirement of the [ACA] that would impose a fiscal burden on any State or a cost, fee, tax, penalty, or regulatory burden on individuals or health care providers” and called for “greater flexibility to the States.”

And he cited new rules issued by HHS in April 2017 to reduce the open enrollment period for the individual market by half, add documentation requirements for those buying plans under special enrollment periods — such as after getting married or having a child, allow insurers to require past-due premium payments before an individual could reenroll, and allow a little more variation for insurers in actuarial value requirements for plans. Actuarial value is the percentage of health care costs paid by a plan for the population of enrollees.

In our interview with Cox, she noted that shortening the open enrollment period could be seen as a way to limit the enrollment of those with medical conditions, which would drive down premiums. But that began last year.

Premium Increases Since 2014

Overall, experts talk about the long-term trajectory of these individual market premiums under the ACA.

The ACA’s exchanges, and new individual market rules, launched in 2014. Among the major provisions: The law prohibited insurers from pricing plans based on health status or gender, required insurers to accept all consumers regardless of health status, set minimum benefit standards for plans, and required individuals to have insurance or pay a penalty.

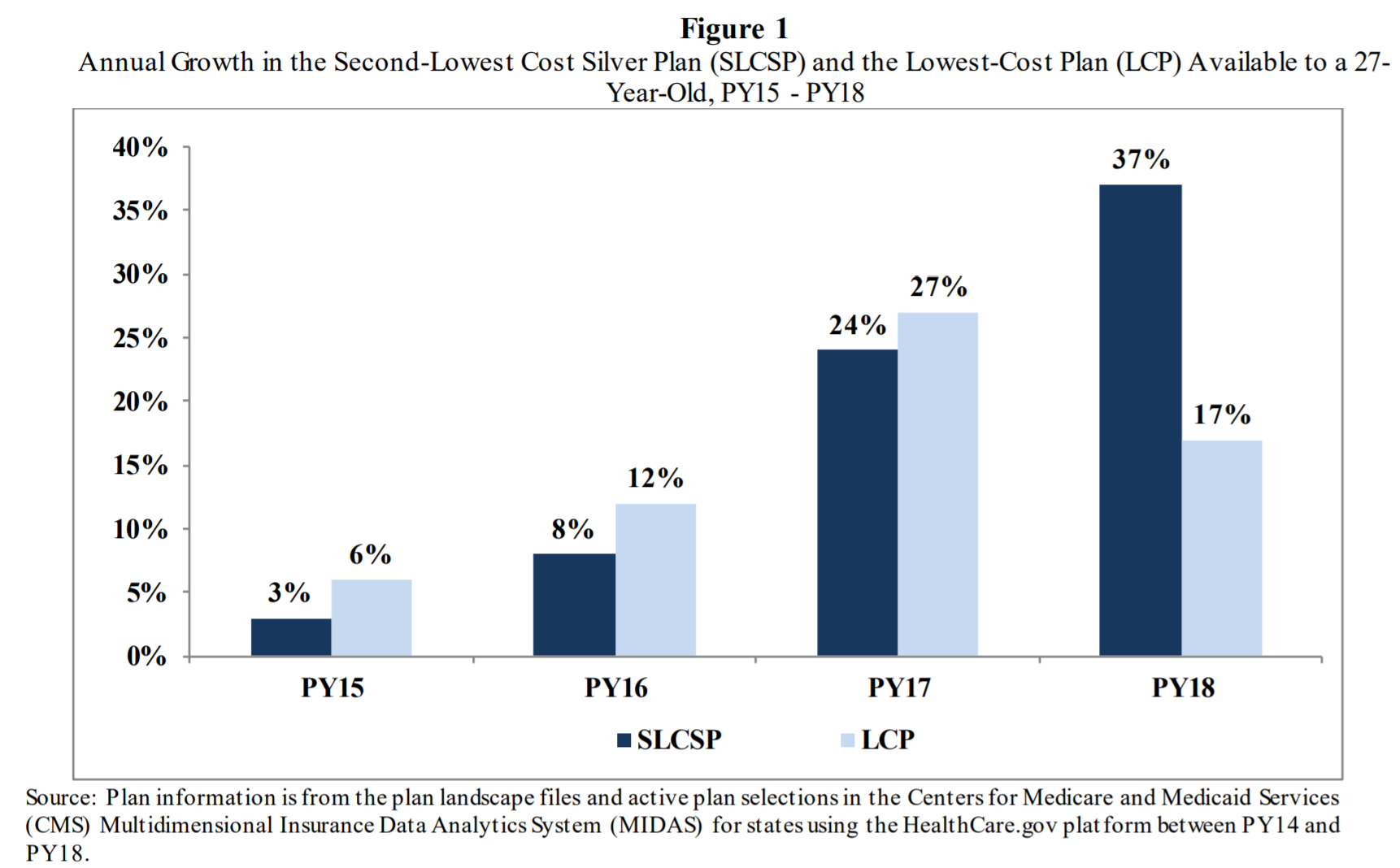

Here’s how premiums have increased each year since then, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, for plans on HealthCare.gov for a 27-year-old. (Individuals can buy plans directly from an insurer or through a broker as well, but those getting subsidies must buy through HealthCare.gov or a state-run exchange.)

Note: “PY” stands for plan year. The 2018 plan year premiums would have been set in late 2017.

Similarly, the Kaiser Family Foundation has measured the average premiums for the second-lowest cost silver-level plan for a 40-year-old, weighted by the plan selections in each county. That shows a 1 percent increase from 2014 to 2015, 8.3 percent increase from 2015 to 2016, 20 percent increase from 2016 to 2017, and 34 percent increase from 2017 to 2018.

Cox told us there were some “growing pains” in the first few years of the ACA exchanges, as insurers learned how to operate in this market.

The increase from 2016 to 2017, said Fiedler, was a “correction year,” as insurers had underpriced in the first few years of the ACA. And then, for the 2018 plan year, the increase was driven by uncertainty over the future of the health care law, and the administration’s decision to end the cost-sharing subsidies.

Mendelson said it takes time for new markets to stabilize, and that’s finally happening in the post-ACA individual market as the political disruption has died down this year. The slowdown in premium growth for 2019 is “part of a natural process of stabilizing the market,” he said.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: