President Donald Trump has repeatedly said that his administration has “lifted 10 million people off of welfare,” a figure that primarily includes the change in the number of recipients of food stamps, but also those enrolled in other programs. While it’s clear enrollment has declined by millions, there are some caveats to the president’s number.

Due to overlap in participation and other factors, it’s unclear whether the figure is exactly correct. The bulk of the 10 million comes from a drop in food stamp recipients, a figure that has been declining since 2013, expectedly so, as the economy has improved. Other conditions may have played a role in the decline in Medicaid coverage.

The president made this claim in his State of the Union address in early February and has repeated it several times since in campaign rallies, often mentioning food stamps, formally called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. When we reached out to his campaign, it pointed also to figures on enrollment in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (the cash-assistance program most often referred to as “welfare”), and the Supplemental Security Income program for disabled adults and children.

The White House Council of Economic Advisers reports have pointed not to SSI but rather Social Security Disability Insurance, another program for disabled adults who are unable to work. A Feb. 20 CEA fact sheet on the White House website, for instance, talks about the job market and income growth “pulling people out of poverty and off means-tested welfare programs.” It goes on to provide some numbers: “Food insecurity has fallen, and there are nearly 7 million fewer people participating in SNAP than there were at the time of the 2016 election. The caseload for TANF has fallen by more than 900,000 individuals, and the number of individuals on Social Security Disability Insurance has fallen by almost 400,000 since the 2016 election. Similarly, Medicaid & CHIP enrollment reported by States is down by 3 million.”

The SNAP figure is actually closer to 5 million, but the other figures are largely correct. Either way, one can get to nearly 10 million with SNAP, TANF and Medicaid/CHIP. However, because of overlap between the enrollments in the programs, it’s not clear how many individual “people,” as Trump has put it, have left these programs during his administration.

It’s even possible the true number of individuals is higher, because what the monthly enrollment figures show are that more people are leaving the programs than joining them. Trump would be on firmer factual ground to say 10 million is the change in average monthly enrollment in these programs under his administration.

Perhaps a more important caveat is the trend in most of these programs predates the president’s time in office. Enrollment is generally supposed to drop in most of these programs when unemployment is low and the economy is doing well — and the figures should grow during an economic recession.

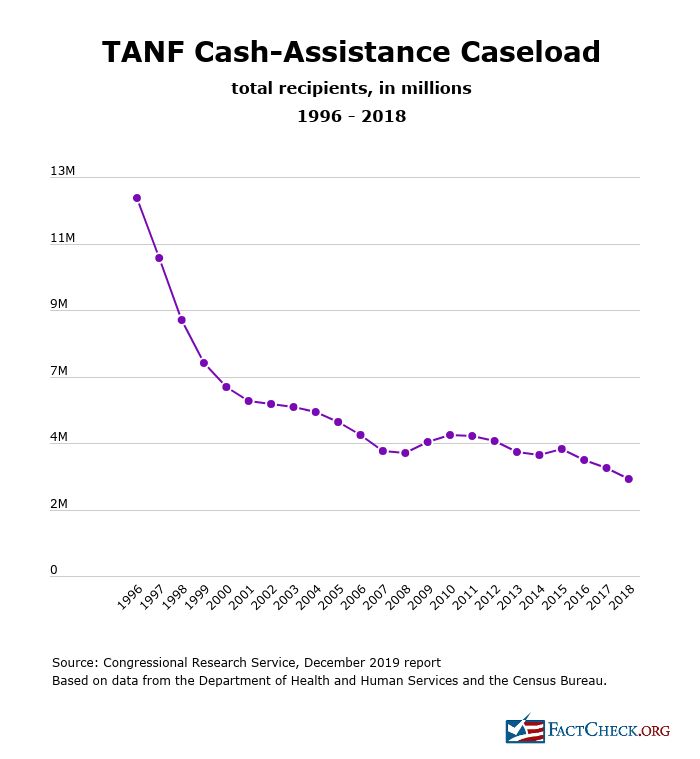

Back in 2017, when Trump promised to lift “millions” off welfare, we noted that the welfare rolls, meaning TANF, had already declined by millions — from 10.9 million average monthly recipients in fiscal 1997 to 2.8 million in fiscal 2016, a reduction sparked by 1996 legislation signed by then-President Bill Clinton to put work requirements and time limits on TANF.

But if he were including SNAP and other programs as “welfare” then, the promise wouldn’t have meant much.

Let’s take a closer look at these programs and the trends over time.

SNAP

The president often specifically mentions food stamps, or SNAP, saying as he did on March 2 at a rally in North Carolina: “We have lifted 10 million people off of welfare, including 7 million people off of food stamps.” But that figure is inflated, and the issue involves the state in which he was speaking.

The official U.S. Department of Agriculture figures on SNAP appear to show the national monthly number has declined by 6.5 million since Trump took office in January 2017. However, all months after fiscal 2017 don’t include data from North Carolina, as the USDA table notes. The true figure is closer to a 5 million decline.

North Carolina does provide figures on a state website, and those show nearly 1.3 million people participated in the state program in November 2019, the latest month for which USDA has national figures. So, adding North Carolina back into the latest U.S. statistics, would put the decline in enrollment under Trump at 5.2 million.

The economy is “the biggest factor in SNAP” enrollment, Dottie Rosenbaum, a senior fellow with the liberal-learning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, told us in an interview. While there could be other reasons the numbers move, such as policy choices in individual states, it’s mainly about the economy and poverty levels.

“Trends in SNAP caseloads follow trends in poverty,” Rosenbaum, whose research focuses on SNAP, said, adding that this trend started before Trump took office and has continued. “The fact that SNAP has come down shows that it’s working as intended.”

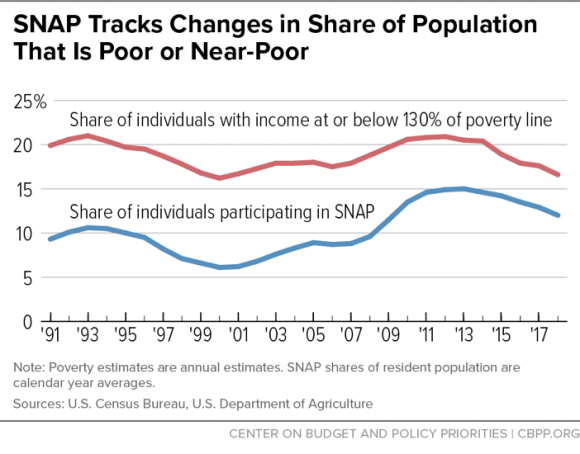

This chart from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows how enrollment mirrors poverty figures:

As we’ve written before, the number of Americans getting food stamp assistance grew during the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and after, as the stimulus legislation increased benefit levels. Enrollment peaked in December 2012, when 47.8 million individuals participated in the program. But as the economy improved, that figure fell.

By the time former President Barack Obama left office, the monthly number of people enrolled in SNAP had dropped by 5 million from the December 2012 peak to January 2017, a bit more than four years.

In nearly three years under Trump — 34 months, given the most recent USDA data — the enrollment has declined by another 5.2 million.

The figure may further decline due to factors beyond the economy, such as administration changes to eligibility, but those haven’t yet gone into effect. A USDA rule for tightened requirements on able-bodied adults without dependents is set to go into effect on April 1 and would reduce SNAP eligibility by 688,000 people next fiscal year, according to the USDA analysis.

Last summer, the administration said another proposal could reduce SNAP enrollment by 3 million by limiting state flexibility regarding income and asset levels of recipients.

Medicaid and CHIP

Medicaid and CHIP enrollment has declined by 3.9 million from Jan. 2017 to Nov. 2019 (the most recent preliminary figures available). But it’s not possible to simply add that figure to the decline in SNAP to get the number of “people” who moved off of these programs. There’s substantial overlap in the two programs.

We don’t know precisely what the overlap is, or whether people who moved off one program since 2017 would have also moved off the other.

In 2016, the Urban Institute estimated, based on 2013 data — before the ACA’s Medicaid expansion — that 59% of children, 54% of parents and 23% of nonparents who were eligible for either SNAP or Medicaid/CHIP were also eligible for the other program. That’s eligible, not necessarily enrolled in both. But the ACA would have increased those figures in the 36 states, plus Washington, D.C., that adopted the expansion.

Urban Institute researchers, in a report produced for the Department of Health and Human Services in 2013, found that if all states implemented the expansion, 97% of SNAP recipients and 99% of TANF recipients would be eligible for Medicaid and CHIP.

Again, not all states expanded Medicaid and not everyone eligible for these programs enrolls in them. As for participation estimates, a 2016 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report said, “About three-quarters of households receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) benefits in 2014 had at least one member receiving health coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program.” And the Bureau of Labor Statistics looked at 2014 Census data on families with children under 18 and found 23.7% of those getting government assistance were enrolled in both Medicaid and SNAP.

Generally, the SNAP income limit for eligibility is 130% of the federal poverty level, CBPP said. Medicaid requirements vary by state, but the limit is 138% for the states that implemented the ACA expansion.

Rosenbaum told us in some states, the same agency administers SNAP and Medicaid, making it more likely that those who left one program would have left the other. But it’s hard to know what may have happened in states that administer the programs separately. “There’s no way to know on an individual level how many fewer people participated,” she said. “All of this is about the decline in the average monthly number of participants.”

The White House Council of Economic Advisers said the drop in Medicaid participation “is predominantly due to a reduction in the number of Medicaid-eligible individuals because of income growth, not eligibility restrictions.”

Samantha Artiga, director of the Disparities Policy Project at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation and associate director for KFF’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, told us that “some” of the drop — which reverses the trend of growing enrollment after the ACA — “may reflect individuals moving to other coverage as a result of increases in income or changes in employment amid the improving economy.” But, she said, some who have left Medicaid/CHIP have likely become uninsured, since “survey data also show a recent rise in the uninsured rate, driven by decreases in Medicaid and CHIP coverage.”

Other factors may be at play in the Medicaid/CHIP decline.

“Experiences in some states suggest that some eligible people may be losing coverage due to difficulties completing processes or providing information to maintain coverage, for example, if they do not receive or have difficulty understanding notices or information requests from the state,” Artiga said in an email. Also, “the administration has reduced funds to support outreach and enrollment assistance, which is often an important for getting and keeping eligible families enrolled in coverage. Moreover, a growing body of research indicates that the shifting immigration policy environment, including recent changes to public charge policy, may be deterring some families from enrolling themselves or their children in coverage or continuing coverage at renewal.”

The administration finalized a new so-called “public charge rule” that could deny green card status to legal immigrants who received Medicaid and other federal benefits. A September KFF report estimated the rule, which went into effect on Oct. 15, 2019, could cause 2 million to 4.7 million people to drop out of Medicaid and CHIP.

There’s also evidence that some, including those not actually affected by the rule change, have withdrawn from the programs. In a 2019 KFF/George Washington University Survey of Community Health Centers, 32% of health centers said “many or some” patients who were immigrants disenrolled or didn’t renew Medicaid coverage over the previous year, and 28% said patients had done the same for their children. The survey was conducted from May to July last year.

A July 2019 report from CBPP said the economy “cannot explain the full national enrollment decline.” For one, that report found no relationship between changes in enrollment and changes in states’ unemployment rates, concluding that the causes for the Medicaid/CHIP enrollment decline “likely vary across states.” It pointed to the Arkansas work requirements instituted in June 2018 (now blocked by the courts) and “increased red tape” in other states hindering enrollment.

TANF

Enrollment in TANF — the cash-assistance program typically considered “welfare” — has declined by 825,145 from January 2017 to June 2019, the most recent figures available. That includes enrollment in the State Supplemental Program, state cash-assistance that’s based on Supplemental Security Income eligibility.

Children make up the vast majority of TANF enrollment. In 2018, 74% of recipients were children, according to data in a Dec. 30, 2019, report by the Congressional Research Service.

There’s also substantial overlap between TANF and SNAP: 82% of TANF families also received SNAP, according to fiscal 2018 figures from the administration.

The CRS report said over the long-term, the economy has affected the caseload of TANF, though other factors, such policy changes, also have played a role. As we mentioned, TANF enrollment has dropped precipitously since 1996 welfare legislation was enacted under the Clinton administration. CRS figures show the number of families enrolled in TANF increased from 2008 to 2010, during and just after the Great Recession, but then began to fall.

SSDI

The White House economic advisers’ report includes Social Security Disability Insurance as a “means-tested welfare” program, but Kathleen Romig, a senior policy analyst at CBPP, objects to that characterization. “Social Security Disability Insurance is not a means-tested ‘welfare’ program at all,” she told FactCheck.org. “Like the rest of Social Security, it is a social insurance program that requires beneficiaries to have substantial work histories, and benefits are based on contributions to the program.”

In fact, SSDI provides benefits for those unable to work due to a medical condition that lasts more than a year or causes death.

Romig said the administration’s figure of a 400,000 decline since the election was actually too low. The available SSDI statistics online are only current through December 2018. The drop continues a trend that CBPP noted in a January report. The decline in both applications and enrollment since 2010 is partly due to the economy, though other factors are likely at play. The CBPP report included several possibilities, such as paperwork requirements.

The Congressional Research Service cited several factors in a November 2018 report: demographics (baby boomers reaching full retirement age followed by a smaller cohort of those of typical disability age), added jobs post-recession, the Affordable Care Act, and a smaller share of applications being approved.

Overall, Trump is correct to cite a decline in enrollment in these programs, largely due to economic factors. But such trends, other than with Medicaid, began before he took office, and we can’t say whether his 10 million “people” claim is correct. Administration policies to decrease eligibility for SNAP and Medicaid also are expected to begin to have an effect.